Columns

– No tree is solitary in Kumano –

Artist Geert Mul wrote this essay during his stay in Kinan Art Residence Vol.2 in July and August 2024.

【No tree is solitary in Kumano】

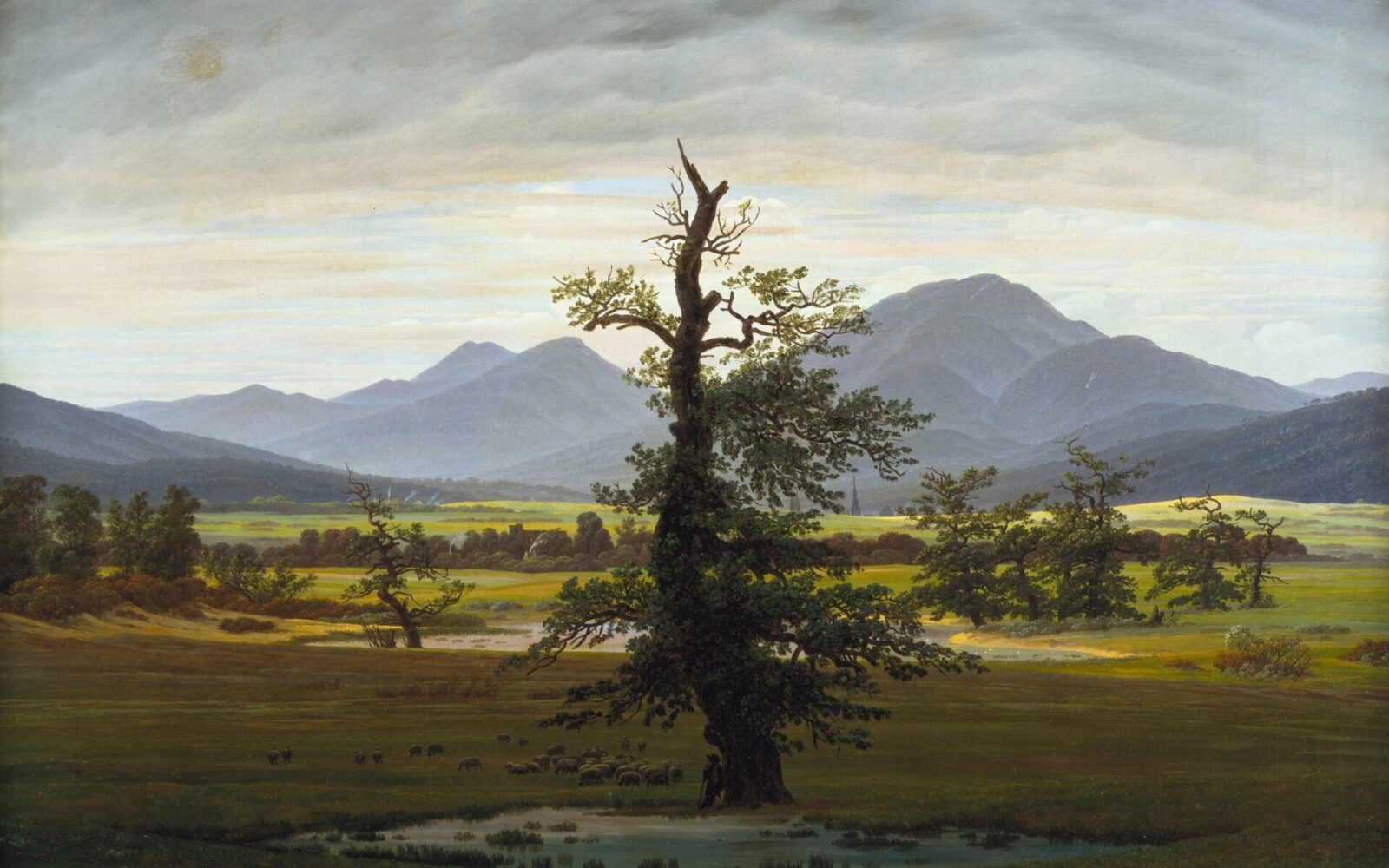

In recent years, some of my artistic work has gradually gravitated towards this

folkloric theme of the solitary tree. Looking at a solitary tree is like looking at a

person. More specifically, you quickly identify the tree with yourself, in a mood that

relates to the tree’s characteristics.

In Western art history, ‘landscape’ is rarely the subject of a depicted landscape.

Through the use of linear perspective, the viewer is placed at the center of the

landscape. And almost always, human figures are present in the images;

insignificant compared to nature, but that is precisely the message, with ‘nature’

serving as an analogy for the universe and/or the divine.

In art, ‘landscape’ is not an image of nature but an image of ‘us’. The solitary tree

reflects the solitary individual; la condition humaine.

I am writing this at a wooden table in a Japanese house in the town of Tanabe in the

Kumano region of Wakayama, a peninsula south of Osaka. Here, I am working on a

creative research project about the life, philosophy, and work of the brilliant

Kumagusu Minakata (1867-1941), who grew up and worked here. Inspired by

Minakata’s fusion of spirituality, nature philosophy, and science, I aim to deepen my

artistic practice by exploring the interaction between nature and culture and their

technological mediation.

As part of this research, I am seeking ancient, solitary trees to create monumental

photographic artworks. I expected to find many of these trees in this vast area of

forests, mountains, pilgrimage routes, and temples, but the region’s history tells a

different story:

The reforestation of Kumano around 1915-1920 was a large-scale Japanese

government project aimed at restoring forests damaged by logging and agriculture,

but economic and political interests were also significant. The project focused on

planting monocultures of commercial species such as Japanese cedar and cypress,

causing deciduous trees like oak, maple, and beech to nearly disappear.

During this reforestation period, the Japanese government also implemented

policies aimed at reducing (demolishing) the number of small, local temples and

shrines, of which there were hundreds in this area. This was done to cut costs and

increase administrative efficiency, but the policy was also driven by an ideological

politics from the Meiji period. Kumagusu Minakata was highly critical of this policy

and, as an early climate activist and scientist, successfully advocated for the

preservation of biodiversity and the network of smaller Shinto shrines and temples.

Geert Mul. 1200 years old Camphor tree at Tokei-Jinja Shrine, Tanabe, Wakayama.

In Shintoism, where spirituality and nature come together, there is a strong

connection between shrines (jinja) and ancient, special trees. Shrines are often

surrounded by sacred forests, known as ‘chinju no mori’, which are protected and

serve as refuges for local biodiversity.

As a result of this history, ancient solitary trees are now almost exclusively found at

the many Shinto shrines in Kumano. The tree is marked and honored with a rope

(shimenawa) and a folded paper streamer (shide), serving as a key connection

between the physical space and the spiritual dimension of the shrine.

In this way, the tree is integrated into a network of cultural and religious meanings,

breaking its solitude and anchoring it within a vibrant community of nature and

spirituality. Thus, these solitary trees are not ‘solitary’ at all. On the contrary, they are

part of a community.

In Kumano, the freestanding tree also reflects ‘la condition humaine’, but here it is

not a solitary individual condition, but rather a deeply rooted spiritual and social

condition.

【Artist】

Geert Mul

Tanabe, Kumano, Wakayama, Japan 28-07-2024

This essay was written during a practice-oriented creative research residency in

Japan, July and August 2024. The research is inspired by the idiosyncratic

Japanese naturalist, ethnologist, and folklorist Kumagusu Minakata (1867-1941).

The residency is in Tanabe, Wakayama, a natural area where Kumagusu Minakata

was born and worked and where the Minakata Kumagusu Museum and archives are

located.

Supported by Kinan Art Week

Stimuleringsfonds Creatieve Industrie NL