The Myth of Nature: Kumagusu Minakata’s Creation Myths.

Introduction:

Kumagusu Minakata (1867–1941) was a groundbreaking Japanese naturalist, ethnologist, and polymath whose studies of nature spanned Western, Chinese, and Japanese science, folklore, and spirituality. His largely autodidactic, creative, interdisciplinary approach, shaped in part by the Buddhism of Wakayama and Shintoism, distinguished him within both Eastern and Western traditions.

Minakata’s legacy also lies in his ability to connect scientific research with broader social, spiritual, and philosophical issues. His writings, often focused on nature studies, contain both scientific details and poetic reflections, as well as drawings. Today, his ideas seem more relevant than ever, resonating in discussions on humanity’s relationship with nature, identity politics, queer studies, and critiques of capitalism and nationalism.

This essay is inspired by the work of Kumagusu Minakata, who developed a theory of civilization with the slime mold as its foundation. While this may seem peculiar at first, especially from a Western perspective, Minakata’s theory of civilization provided an alternative to 19th-century social Darwinism, where Charles Darwin’s theory of ‘natural selection’ was reduced to a capitalist politics of ‘Survival of the Fittest.’ In other words, Western capitalism and neoliberalism can also be understood through the analogy of a framework built upon a cultural definition of ‘nature.’

My essay is a plea for the creation of a nature in which humanity takes full responsibility for creating a humane world. By defining art as a ‘creation myth’ (since a creation myth is already a form of poetry or prose), I explore the power (including its retroactive power) of art and its media to create such a nature.

The legacy of Kumagusu Minakata serves as a catalyst to explore and reconsider, through art, the interconnected concepts of nature, culture, ideology, spirituality, and technology.

The Creation of Western Nature:

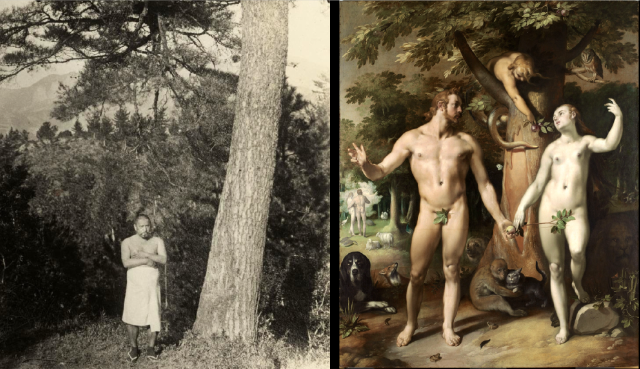

In the 1592 painting The Fall of Man by Cornelisz van Haarlem, the Biblical story of Adam and Eve in the Garden of Eden from the Book of Genesis is depicted (see illustration above right). Although this story is generally interpreted as a reflection on human responsibility and the awareness of good and evil, I see in this prose primarily the creation of the Western concept of nature: at the beginning of this story, there is no distinction between man and nature in the Garden of Eden. The garden is described as a place of harmony, where humans, plants, and animals live equally and peacefully. Until man acquires ‘knowledge’ by eating from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil. At this moment, God intervenes and banishes man forever from the Garden of Eden. From that point on, the world is divided into two camps: on one side, a garden with animals and plants (nature), and on the other side, forever separated from nature: man with knowledge (culture).

Content:

This creation story plays a central role for both it’s content and its form in this essay. As a story, it reveals a fundamental aspect of the Western concept of nature: the separation between man and nature. Nature is being defined as a world separated from humans and culture. The critique of this relationship to nature describes this concept as ‘anthropocentric.’ The critique of anthropocentrism focuses on the idea that man is the center of everything because ‘the world’ ultimately exists to serve man. In the Biblical view, man is the steward of nature, acting on God’s command; in capitalism, nature is reduced to a means of production. In both cases, nature remains under the control of man.

An alternative to anthropocentrism is eco- or biocentrism, where the ecosystem as a whole is central. This perspective emphasizes the intrinsic value of all living beings and their interdependence, regardless of their usefulness to humans. In this view, man is not placed above nature but regarded as an equal component. Yet, this concept still defines nature as a world separated from man and culture, like the Biblical definition. Moreover, both man and nature in this concept are subordinated to an undefined higher (natural?) order to which they must conform.

I believe Kumagusu Minakata offers an alternative and relevant perspective that transcends both anthropocentrism and eco- or biocentrism.

Form:

The creation story of the Garden of Eden illustrates how powerful the creation myth acts as a cultural form: it is able to create a world. The creation of ‘nature’ through this story has endured for thousands of years in Western culture.

How does that work? A creation myth creates a world by narrating the origin of that world. It is a paradoxical creative form; a creation story is a self-fulfilling prophecy, but with retroactive force.

In my (thinking about) art, the creation myth plays a crucial role as a cultural form that encapsulates the essence of poetry, art, and creation. Stories, poems, artworks, and also science, which have re-imagined ‘nature’ for thousands of years, function as ‘creation myths.’ Art as a creation myth is not only capable of presenting an alternative representation of nature but also of creating a different nature. I believe Kumagusu Minakata uses this ‘cultural creative form’ to create a new nature.

From Japan to ‘the West’ and Back to Japan:

At the age of 20, Kumagusu Minakata went to the United States in search of knowledge and progress in Western methodologies and the study of nature, as well as in Western culture as a whole, of which he had high expectations. In 1887, he researched the local flora and fauna in Florida and moved to London in 1892, where he studied at the British Museum until 1900. During these long stays, he relied on self-study, fieldwork, and correspondence with leading scientists.

After returning to Japan in 1900, Minakata specialized in the study of slime molds—organisms that blur the boundaries between plants, animals, and fungi. He concluded, perhaps to his own disappointment, that the biological and ecological approach provided no meaningful insights or even a perspective on the phenomenon of slime molds. On the contrary, binary and reductionist scientific categories such as man/woman, unicellular/multicellular, animal/plant, and life/death were either irrelevant to slime molds or only applicable to specific isolated stages of their life cycle. The result of classifying within these frameworks would, paradoxically, deny their unique properties and existence.

Nature as a Model for Civilization:

When we question the concept of ‘nature,’ it is naïve to assume that merely invoking the term ‘nature’ creates a common basis for discussing ‘its’ properties. An assumed universal ‘nature’ is problematic because the concepts of universality, as history has shown, exclusively reflect the ideologies and technologies of the ruling powers. For example, the Japanese word for external, objective nature (shizen, 自然) was only widely used in Japan in the 1890s. Kumagusu rarely used shizen, even after it became a common part of everyday language. Kumagusu’s concept of intrinsic nature is shaped through his writings, but without nature taking the form of a fixed term.

Kumagusu recognized that the Western model of civilization at the end of the 19th and beginning of the 20th centuries was shaped as an analogy of ‘nature’ through social Darwinism. He also saw that social Darwinism justified inequality, colonialism, and hierarchies of race, class, and gender as ‘natural’ outcomes of the concept of ‘survival of the fittest’ attributed to Charles Darwin. This reinforced Minakata’s belief that the Western model of civilization was not necessarily desirable. As was evident in the shortcomings in studying the slime mold, it was not inherently superior to ‘traditional’ and ‘indigenous’ knowledge systems such as Buddhism, Shinto, and honzōgaku.

Kumagusu Minakata was inspired by the unique, inductive, and eclectic nature of slime molds, which led him to develop a utopian theory of civilization. He challenged fundamental concepts such as race, gender, and nationality, drawing parallels with how slime molds transcend Darwinian binary oppositions, categorization, and hierarchies. Minakata argued that true civilization requires a collective and cooperative development of what he called ‘affective human nature,’ emphasizing intimacy and mutual understanding beyond hierarchical structures.

Minakata’s Personality:

It seems that Kumagusu’s motivation to study slime molds stemmed from an intrinsic curiosity—he had been collecting fungi since his childhood—and a desire to learn from them. Kumagusu Minakata was self-taught but spoke and read not only Japanese, but also German, English, Latin, and Chinese. He corresponded with prominent Japanese politicians, writers, Buddhist monks, and Shinto priests, as well as internationally by notable scientists such as William Bateson, a British geneticist and one of the founders of genetics. He had a strong and distinctive personality, known for his conspicuous and anachronistic clothing choices, such as kimonos, deliberately deviating from the fashion of his time. He had a fondness for alcohol, which also led to anecdotes about his wild and impulsive behavior during social gatherings. Minakata communicated in a direct and unconventional way. He was outspoken and willing to discuss controversial topics, often with humor and sharp wit. However, he was certainly not a ‘socialite’; his life was often characterized by isolation and poverty. He preferred a life in nature and spent much time alone. And then there was Minakata’s homosexuality. He had several romantic relationships, often with men, and was open about this aspect of his life in writings and correspondence. In Japan’s cultural history, homosexuality was accepted to a certain degree and within certain social classes and contexts, but Minakata would have encountered zero tolerance in the United States and England at the turn of the 20th century, where in the ‘enlightened’ West, there was harsh repression and violence against homosexuality.

In Eiko Honda’s paper Minakata Kumagusu and the Emergence of Queer Nature: Civilization Theory, Buddhist Science, and Microbes,1887–1892 she introduces the concept of ‘queer nature’ in relation to Kumagusu Minakata’s concept of nature. She defines ‘queer’ in this context as a way of knowing and experiencing nature that challenges traditional epistemological and hierarchical structures. ‘Queer nature’ invites an intimate and experiential approach to the multiplicity of nature, especially the microbial world. Kumagusu Minakata’s independence and refusal to conform to the social expectations of his time cannot be separated from his affinity for other life forms that challenge cultural-scientific conventions: the slime mold.

The Myth of the Machine:

In the same period that Minakata studied slime molds in Japan, at the beginning of the 20th century, European archaeologists in Egypt were searching for a machine near the pyramids. In Western Europe, in the midst of the Industrial Revolution, it was difficult to imagine how one could build a pyramid without a machine. It was assumed that advanced technology or a physical machine would have been needed to construct the pyramids. But that machine was never found. Interestingly, Lewis Mumford argues in his book The Myth of the Machine that the “machine” that built the pyramids did exist, but it was not a physical device, as 20th-century Western archaeologists had assumed. Instead, this “machine” was a soft machine, consisting of mathematics, language, politics, hierarchy, and human labor; in other words, the machine is a social system.

With this statement, Mumford blurs the supposed hard ontological boundaries between the physical machine on one hand and shared values, norms, customs, knowledge, beliefs, and culture on the other. He also emphasizes the recursive relation between culture and the machine; they define each other because “the machine” (technology) ultimately, like “nature,” forms a condition for human existence and development.

The Myth of Nature:

Can we apply Mumford’s concept of ‘the myth of the machine’ to nature? What if we move beyond the Western concept of nature from the creation story, in which nature is neither human nor cultural? What if we acknowledge that ‘nature’ consists of mathematics, language, politics, hierarchy, human labor, and technology; nature as a socio-cultural phenomenon. The acceptance that the boundaries and overlaps between humans, machines, and nature are the result of an ontological and cognitive politics lays the groundwork for a possible revision of nature, and consequently, a revision of the relationship between humans and nature. It opens the door to an integrated vision and critique of the concepts of ‘nature’ and ‘technology.’

Kumagusu Minakata’s Ontological and Cognitive Politics:

Minakata was fascinated by how slime molds could solve complex problems, such as finding the shortest path to food, without a central nervous system. He viewed this as an example of organic intelligence that is not dependent on hierarchy, but arises from cooperation and mutual dependence. The slime mold functions as a collective organism, with individual cells working together for the greater whole, without a clear top-down structure. For Minakata, this symbolized an ideal model for human civilization, where mutual respect and cooperation are paramount. Slime molds are extremely flexible and continuously adapt to changing conditions. This reflected Minakata’s belief that both nature and civilizations must be dynamic and able to change in order to survive.

Minakata did not view nature as a collection of separate objects but as a holistic, interconnected whole. Every life form, no matter how small or inconspicuous, contributed to the balance and survival of the ecosystem. He opposed the Western and Japanese imperialist idea that nature is a source of raw materials to be exploited by humans. Minakata combined his scientific observations with spiritual insights from Buddhism and Shinto. For him, nature had not only a physical but also a spiritual dimension, in which harmony and respect were essential.

Minakata saw the slime mold as a microcosmic reflection of how nature and society should function: dynamic, interconnected, and without dominant structures. His approach offered an alternative to the dominant hierarchical and exploitative views of his time, with a focus on harmony, cooperation, and mutual dependence. For Minakata, the slime mold was not only a biological wonder but also an inspiration for an inclusive and balanced vision of life.

His struggle against the dismantling of Shinto shrines (the “Shinbutsu Bunri” movement) illustrates his resistance to the loss of local culture and ecology through government policies that copied Western models.

A plea for a Myth of Nature inspired by Kumagusu Minakata.

In my vision or imagination of Kumagusu Minakata, he was aware of his role in the ontological and cognitive politics that could be played out through a Myth of Nature. By recreating nature, he began to unravel the recursive loop of individual cognition and perception, culture, nature, and technology. Kumagusu Minakata’s nature took shape through his empathetic and rational genius, his eclectic and non-conformist personality, and his transdisciplinary creative method, in which knowledge systems such as Buddhism, Shintoism, honzōgaku (the study of medicinal plants), and Western science were integrated. I doubt he could have ever imagined how large and lasting his influence would be on Japanese popular, critical, cultural, spiritual, and scientific thought.

While I am only scratching the surface of Kumagusu Minakata’s legacy, I feel honored to testify to his legacy, to embrace it and hopefully encourage others to do the same. In Western culture, Kumagusu Minakata remains largely unknown, which makes us all a little poorer than we should be.

This is a plea for the creation of a creative-nature inspired by Kumagusu Minakata. A Myth of Nature in which humanity finally emancipates itself fully and takes responsibility for the creation of a humane world, or the failure to do so. ‘The desert,’ or ‘the jungle,’ or ‘the sea,’ as cultural concepts, do not make them any less real. You can still get lost in them and die. (My personal minimal requirement for the definition of ‘nature’.)

Geert Mul

December 2024

This essay was written during a practice-oriented creative research residency in Japan, 2024. The research is inspired by the idiosyncratic Japanese naturalist, ethnologist, and folklorist Kumagusu Minakata (1867-1941). The residency is in Kii Tanabe, Wakayama, a natural area where Kumagusu Minakata was born and worked and where the Minakata Kumagusu Museum and archives are located.

Supported by Kinan Art Week

Stimuleringsfonds Creatieve Industrie NL

Special thanks to Eiko Honda, for sharing her brilliant paper: Minakata Kumagusu and the emergence of queer nature: Civilization theory, Buddhist science, and microbes, 1887–1892.

Special thanks to Yuto Yabumoto, Yukiko Shikata, and Karasawa Taisuke for sharing their personal thoughts about Kumagusu Minakata with me.

Geert Mul

Geert Mul (1965) is a pioneer in the field of digital art and has been exploring for over 25 years the possibilities of a poetry in the language of new media. This resulted in a flow of experimental artworks in a wide range of media: prints, light-objects, video and interactive/generative computer installations. The interrelationship between technology and perception is a leitmotiv in the oeuvre of Geert Mul. After over 25 years of artistic practice, Geert Mul’s work has evolved into an exploration of the interconnectedness between humanity, technology, and nature. ‘I aim to reconceptualize the perceived divisions and connections between ‘man’, ‘technology’, and ‘the natural’,’. Mul emphasizes that it is literally of vital importance to acknowledge how technology determines our relationship with nature. Geert Mul studied art from 1985 -1990 at the HKA Arnhem where he graduated with computer animations, video and kinetic sculptures. After his studies, he traveled in Mexico, the United States and Asia. He resided for one year in Tokyo. Since 1993 Mul lives and works in Rotterdam, Holland. In the mid-1990s, Mul became one of the first VJ’s, in the alternative Techno scene. These events grew into interactive audio-visual environments, commissioned artworks and installations which were exhibited in a variety of contexts: public space, museums and festivals. Mul exhibited in major musea in The Netherlands: Kröller-Müller Museum, Museum Boijmans van Beuningen Rotterdam, Stedelijk Museum Amsterdam. International: National Museum of Modern Art Kyoto Japan, Museo Nacional Reina Sofia Madrid, Institute Valencia Arte Moderne, Fondation Cartier, Paris, Museum of Contemporary Art Chicago. Geert Mul lives and works in Rotterdam, is represented by gallery Ron Mandos, Amsterdam.