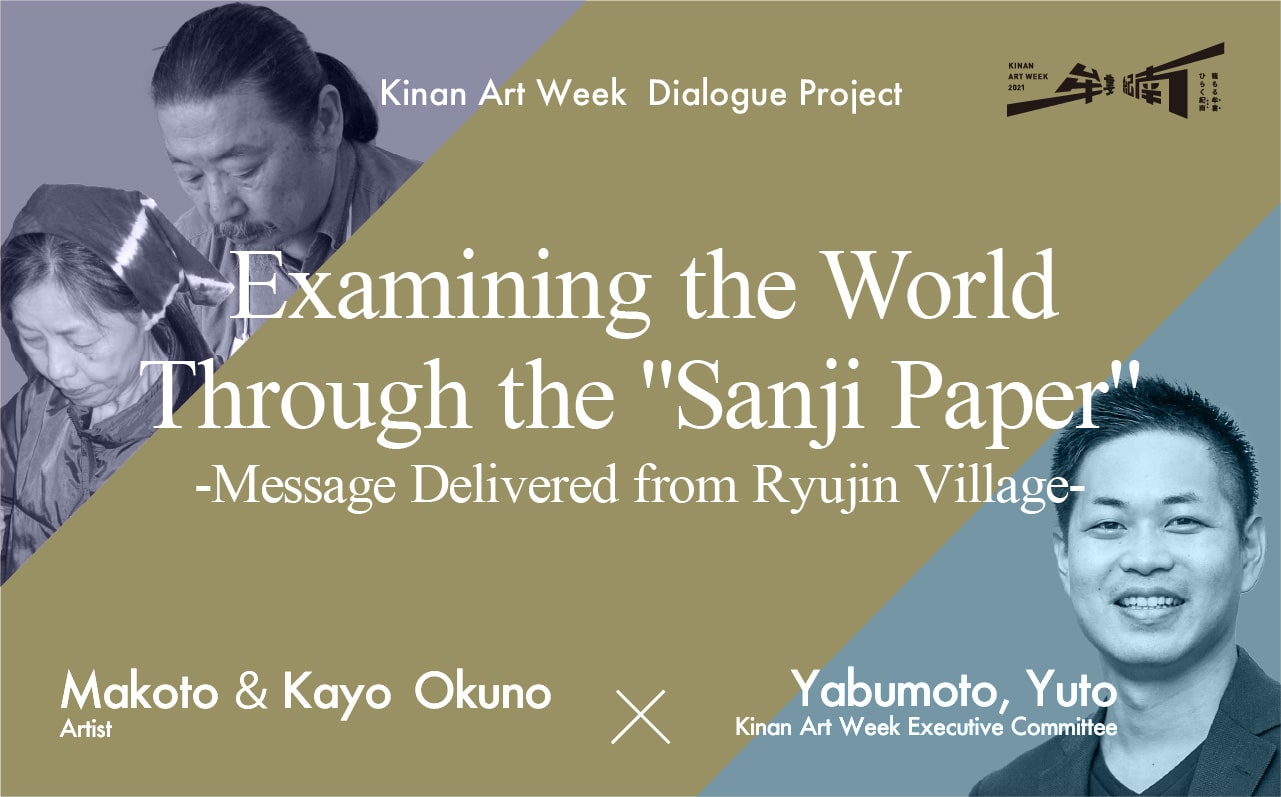

Examining the World Through the “Sanji Paper” ~Message Delivered from Ryujin Village~

Guests

Makoto Okuno, Artist & Kayo Okuno, Artist

In 1984, Mr and Mrs Okuno moved to Ryujin Village, Hidaka-gun, Wakayama Prefecture (now Ryujin Village, Tanabe City), where they were involved in running the Ryujin VillageInternational Art Village. They started a community revitalisation project using a closed school, and revived the Ryujin Village ‘Sanji Paper’ tradition, which had ceased to exist, based on interviews and research into the nature, culture and history of the area. Theycontinue to express themself through the production of figurative works using the papermaking technique, while conveying messages about paper culture and forests. As an environmental education advisor for Wakayama Prefecture, they also conduct classes in which participants can experience the process of paper making from the collection of Kouzo (raw mulberry) trees to the making of paper.

Makoto received the Wakayama Prefecture Master Craftsman Award in 2016, and in 2018 he and his wife held a two-person exhibition in Shanghai, China.

<Interviewer>

Yuto Yabumoto, Kinan Art Week, General Producer<Edited by>

Table of Contents

1. Mr. and Mrs. Okuno

2. Global Issues as Seen Through ‘Paper’.

3. Mr Okuno and the Sanji Paper.

4. Activities in Ryujin Village

1. Mr. and Mrs. Okuno

Yabumoto:

Thank you for your time today.Could you quickly tell us how you decided to start your activities in Ryujin Village, and tell us about Sanji paper, the paper-making craft of Ryujin Village?

Makoto:

I had my own studio in Osaka, where I exhibited my work as a plastic artist in solo and group exhibitions and taught at an art school. Kayo was an art teacher at public junior and senior high schools in Osaka.

We were both teaching in Osaka and showing our work, but decided to quit school jobs to concentrate on production. That was in March 1984. In the spring of that year, Kayo held a solo exhibition at Art Space Niji (*) in Kyoto, and Shozo Shimamoto (*) came to the exhibition. He has passed away, but he was a member of a contemporary art group called the Gutai Art Association.

(*) Art Space Niji – a venue for the presentation of a wide range of experimental works, mainly contemporary and modern art, with exhibitions in a variety of genres Closed 24 Dec 2017.

Reference: Let’s play in Kyoto ART

(*) Shozo Shimamoto – Japanese artist, contemporary artist. Professor emeritus at Kyoto University of Education, professor at Takarazuka University of Art and Design, and chairman of the Japan Association of Artists with Disabilities. He was a founding member of the Gutai Art Association, one of the leading contemporary artists of post-war Japan.

See also Wikipedia.

Mr .Shimamoto was a professor of art at Kyoto University of Education, and he was the village head of the Ryujin International Art Village. He told us, “We opened an art village in Ryujin Village last year, but there is no one to live there. He was wondering if there was anyone who wanted to live there”. At that time, we both had to quit our jobs. I was 31 years old.

I saw the newspaper article about the opening of the Art Village and thought it was very interesting. I thought it was particularly interesting that they brought art to the theme of ‘village revitalisation’.

Kayo:

For some reason, before I met Mr. Shimamoto, I had this image and thought of living in an ‘art village’ in the nature of a mountain village and doing art activities. When I told him about it back home, he was very enthusiastic.

Makoto:

Even though we were talking about revitalising the village through art, the idea in depopulated areas at the time was how to bring culture from the city. I felt that working together with short-term village revitalisation companies would only be a ‘village-busting’ exercise. So, in the process of digging up the history of the past, or rather the culture that lay dormant in the mountain villages, we came across a form of paper making (*) called ‘Sanji paper’ (*).

(*) Sanjii paper – Paper making has been practised in Ryujin village since ancient times. The paper was called ‘Sanji paper’ and was one of the main products of the area, used for a variety of purposes along with the life of the mountain villages. It ceased for a time soon after the war, but in 1984 paper-making began at the former Ryujin International Art Village Art Centre and Sanji paper was revived. Since then, the paper has been produced using herb-dyeing, natural dyeing and new techniques, and continues to be produced to this day. The upper reaches of the Hidaka River are a production area for kouzo (paper mulberry), and Sanji Paper is made from locally produced Kishu kouzo, which are boiled and heated over wood, bleached white with water and the sun, and all processes are carried out by hand.

Reference: National Handmade Washi Federation.

(*) Paper making – The act of scooping paper, especially washi. Also, a person who makes it his profession.

Reference: Shogakukan Digital Daijisen.

2. Global Issues as Seen Through ‘Paper’.

Makoto:

Kayo has always been aware of the idea of reviewing paper. You use paper in art classes, don’t you? The issue of forest resources and paper has always been there, now and in the past.

Yabumoto:

I see. So it is an environmental issue.

Kayo:

We were raising children and were very concerned about the environment.

The work I presented at my solo exhibition in Kyoto was an expression of action painting, where I painted on large sheets of washi with a brush in a variety of colours, with the urge to get inside the paper. When I moved here a month later, I learnt that paper used to be made and thought, ‘This is it;.

Makoto:

I started digging up the village culture, which is how I got into papermaking, but papermaking in Ryujin had ceased after the war. I couldn’t find anything to refer to, so I made my own tools and found the materials myself. I decided that if I couldn’t get everything locally, I wouldn’t make paper, and in the end I was able to get everything locally.

Yabumoto:

Right.

Makoto:

The raw material for Sanji paper is kouzo (paper mulberry) (*), which is made from the peeled bark of steamed logs. There was only one remaining farmhouse that produced kouzo , and the villagers would gather there to work, and every year my family and I would go there to help and learn from them. That is how we started making paper. Now, the agricultural cooperative in the neighbouring village ships the paper. That said, compared to 30 or so years ago when I started making paper, the volume of shipments has decreased by a tenth due to the ageing of the population.

(*) Kouzo – one of the raw materials for washi. It has been used since the Nara period (710-794) and its cultivation became popular from the Muromachi period (1336-1573), along with the demand for paper. In the Edo period (1603-1867), its cultivation was encouraged by the shogunate and clans as one of the three herbs of the four trees.

Reference: Obunsha Encyclopedia of Japanese History, 3rd ed.

Yabumoto:

Will Mr. Okuno be the last bearer of washi in this area?

Makoto:

That’s right. But in my case, I didn’t have the intention of becoming a craftsman in the first place. I wanted to revive it, but I didn’t think about the tradition at first. But when I actually started working on it, I started to see many things from paper.

Yabumoto:

What do you mean?

Makoto:

For example, what was paper before it became paper?

Yabumoto:

It may be a tree.

Makoto:

Right. So what kind of plant was growing where? So maybe this paper was made from a tree that was illegally logged somewhere in Siberia.

Yabumoto:

Is that what you mean? So is there such a possibility?

Makoto:

That’s right. The tree may have been cut by a foreign company in Africa.

Kayo:

Could be a primary forest tree, inhabited by Indonesian wildlife.

Makoto:

It could be thinned wood from Japanese mountains. Or it could be a tree cut to make a road in the mountains. So we don’t know that.

When you make your own paper, you realise that paper is a blessing from the forest.

Also, the white of paper made from kouzo is a natural white. In contrast, wood pulp paper is chlorine bleached and even dyed with fluorescent colours.

Yabumoto:

I see.

Makoto:

Then I wonder what that whiteness is after washing with synthetic detergent, and I think about all sorts of things with the paper as a starting point. Synthetic detergent (*) is said to be made from petroleum residue.

Makoto:

Then, the main source of dioxin in Japan is waste incineration plants, because Japan is the only developed country that burns and disposes of so much waste. The problem has become so great that the release of dioxin into the atmosphere is now regulated.

And after waste incineration plants, it was the paper mills that were generating it. It is a chlorine bleaching process. Papermaking gave me the opportunity to think about environmental issues.

There are other things that have given me cause to think. People say that washi is a traditional Japanese culture, but it originally originated in China. It was brought to Japan and was technically improved, and after the introduction of Western paper, it came to be called washi. It is necessary to rethink how Korean and Chinese culture has been treated in Japan since the Meiji period. In Japanese education, the modern cultures of China and Korea are not taught. This is what I mean when I say that you can see many things from paper.

3. Mr Okuno and the Sanji Paper.

Yabumoto:

How did Mr .Okuno come across the ‘Sanji paper’ when you were digging up the culture of Ryujin Village?

Makoto:

I guess the reason I hit upon papermaking is because I was originally a painter. ‘Painting’ starts with ‘drawing on paper’.

Yabumoto:

So you originally oriented towards “paper”.

Makoto:

I guess that’s what it was for now. I never thought I would become a paper artist , though [laughs].

Yabumoto:

I see. Do you still paint?

Makoto:

As I make various artworks, I paint with various painting materials in the process. For the two-dimensional works I present, I paint with fibres of paper dyed by herb-dyeing. However, if painting is taken as an expressive activity in the broadest sense, the act of making paper itself can be said to be an expressive activity for me. I once did a week-long paper-making performance at the Tokyo Metropolitan Art Museum.

I once painted a dugong on the theme of the Henoko Sea. I raised the issue of concrete blocks being put in the area where dugongs eat eelgrass (*) because of the relocation of the US military base. The picture of the dugong was sold in Shanghai. A female director who was there to cover the event bought it.

(*) Eelgrass: A typical marine flowering plant, growing on shallow sandy muddy seabeds and forming large colonies (seaweed beds).

Source: Shogakukan Encyclopaedia of Japan (Nipponica).

Yabumoto:

When did the exhibition take place in Shanghai?

Makoto:

2018. I’m making these works, so I haven’t interrupted my so-called expressive activity of painting.

Yabumoto:

You and your wife make them together.

Makoto:

Right. She dyes the colours with herb dyes, so there is a division of labour in the material making stage. In paper making, the priority is the material. In contrast, painting is very abstract. Paint is a neutral painting medium, but paper, as a material, is completely an object. It is difficult to collaborate in figurative expression, so most of the time the works are made separately. In some cases, Kayo’s ideas are used to create the work.

4. Activities in Ryujin Village

Yabumoto:

Where do Mr. Okuno’s production activities take place?

Makoto:

When I first started making paper in the Art Village, I lived in an abandoned former junior high school in the Art Village. I used to make paper in the classrooms by putting down blue sheets. But that situation didn’t allow my work to develop any further, so I decided to build a shack behind the school building. So I went to the village hall to ask if I could build a hut for papermaking. Then they said, “Wait a minute. Mr Okuno has revived Sanji paper, so now a council member is proposing a budget to build a papermaking hut. If the council approves it, we will start construction in the summer”. I had no idea about this (laughs).

Yabumoto:

It’s amazing. Ryujin village made it for you, didn’t they?

Makoto:

Yes, that’s right. But a few years ago there was a municipal merger and Ryujin Village became Tanabe City, right? Then the primary school next to the building where we lived was consolidated, and that was the only place they could find to extend the school building to meet the standards of the new school.

Yabumoto:

That’s a lot of work, isn’t it?

Makoto:

We had a separate house, so we didn’t have a problem with where we lived. But I was still working in an abandoned school building.

That’s why the place where I used to work is going to disappear. But Ryujin village couldn’t ask me to leave. It was as an art village that they invited us to come here . The administration of Ryujin village was aware that they had to do something about my workplace, so I made a proposal to them that we could coexist. Tanabe City also appointed a person in charge and formed a committee to discuss various issues, and as a result, the former mother and child centre was revitalised and opened as the Tanabe City Sanji Paper Preservation and Tradition Centre.

Yabumoto:

Is humidity safe for the management of the works?

Makoto:

During the rainy season, I put in a dryer. These buildings get condensation very quickly.

Yabumoto:

Right. By the way, when do you peel the bark of the kouzo?

Makoto:

Harvesting is done during the winter months when the trees are hibernating. This way, the trees are not killed and can be harvested from the same tree that continues to grow year after year. The bundles are steamed in a kamado and peeled. When making paper, the kouzo are softened and boiled using the ashes from the kamado or stove. The ash softens the paper without using chemicals as much as possible. Waste wood is also used as fuel for the stoves.

Yabumoto:

Where did you train in paper making?

Makoto:

I taught myself by asking people who used to make paper in Ryujin and visiting production centres across the country. I didn’t have a teacher. Not having a teacher is a problem in some ways. Everything is self-taught. But I am free because I am not bound by anything. It took me a long time, but I was able to discover the basics of papermaking through repeated failures.

The handmade washi industry also faced competition from Western paper in the Meiji era. As mechanisation took place, tools changed. The Wakayama paper I work with, such as old Ryujin and Koya paper, is made using old methods from before the Meiji era.

Most of today’s papermakers have been doing it since the Meiji era. I don’t mean to deny that. Paper rots quickly in the summer. It is a raw material. That’s why it’s normal for papermakers today to put formalin in the papermaking tank and to use a paper dryer to dry the paper. It is also commonplace to beat the paper with a machine, but that’s fine. I beat by hand, but you can’t do that if it takes so much time and effort.

People call this paper ‘Japanese papaer Washi’, but I don’t use the word ‘washi’ very often. I say ‘washi’ when it conveys the message better, but I don’t like to use it very much.

Yabumoto:

Why is that? Is it because the roots are not ‘Japanese’?

Makoto:

I have the feeling that Japan today is not doing enough to be able to say that ‘washi is Japanese culture’. Nowadays, washi is mostly made from imported raw materials. At the beginning of Japan’s rapid economic growth, the price of raw materials became high, so we took seedlings of the raw material, kouzo , to Thailand, grew them over there and bought the white bark at a low price. However, as the labour costs in Thailand also rose due to economic growth, we used to do this in Laos until a while ago. Now it is in China.

Yabumoto:

I see. How do you distribute washi?

Makoto:

I sell them when I hold exhibitions, and I get orders not only for this kind of paper, but also for fusuma paper, shoji paper, wallpaper, etc. I have to sell my work at exhibitions. I also have a gallery in the village where I sell paper.

Kayo:

I sometimes produce them at the request of architects and clients. I have them handled by shops specialising in washi.

Yabumoto:

It is completely hand-made and amazing. There are almost no other people in the whole of Japan who do this method of production.

Makoto:

That is not true either. There are still some production areas in Japan that are sticking to handmade products and doing their best.

Yabumoto:

Now I would like to ask you one last question: You are making Sanji paper in Ryujin, but is there anyone out there who will be the next bearer of the paper?

Makoto:

My son has been helping me since he was a child, he can handle the whole process and I would like him to take over, but he has children and a family to support. If he can’t eat, he can’t do it. That is a problem.

But many people have entered Ryujin Village after we arrived. It is a place with many immigrants.It became desolate when Tanabe City was established, but the fact that people with rich personalities moved into the village is a result of the “Art Village” project. In 2013, we organised the 30th anniversary and held an event in an abandoned school. We made a tent out of large sheets of paper in the gymnasium. The headmaster of my son’s junior high school helped us.

Yabumoto:

We went to talk to fishermen, kikori (woodcutter) and charcoal makers, and found that it was still difficult to find successors. It would be nice if Sanji paper could also have a successor.

Thank you for your time and for your valuable talk.