Columns

Special contribution#1 “Seclusion, that is, Openness” -Kumagusu sees the ‘macrocosm’ in the microscopic world-

A special contribution from Taisuke Karasawa, a philosophical / cultural anthropologist, who will be on stage at the online talk session “Kinan Chemistry Session vol.2” held on May 28th.

“To find the primordial impulse of life or the breath of life- this quest of Kumagusu is deeply connected with art. “

(Referenced from : text)

The story about Minakata Kumagusu’s view of the universe goes through various inside and outside, and leads to the theme of the session.

Please take a look.

.

Seclusion, that is, Openness

-Kumagusu sees the ‘macrocosm’ in the microscopic world-

Taisuke Karasawa

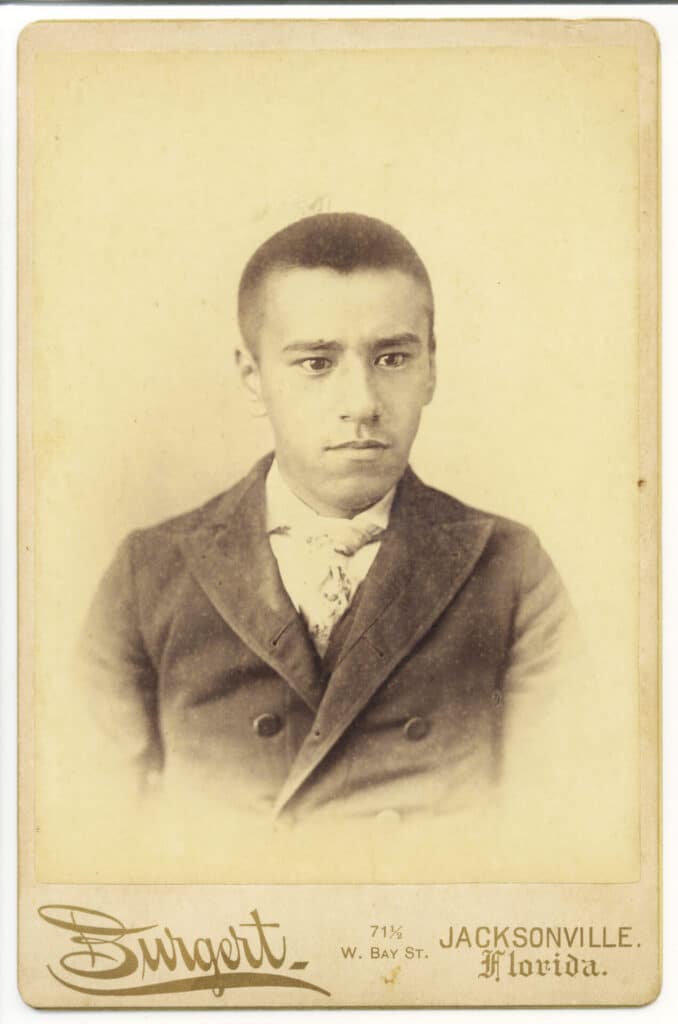

Kumagusu Minakata was born in Wakayama City in 1867. From an early age he had an excellent memory and an extraordinarily inquisitive mind, read various encyclopedias and collected plants and animals. Later, he entered the University Prep School (now the University of Tokyo, College of Arts and Sciences Division). However, in the winter of his second year, he left the school and decided to go to the United States to study. Firstly, he entered Pacific Business College, then Michigan State School of Agriculture. However, neither school satisfied Kumagusu’s thirst for ‘knowledge’. Eventually, he dropped out of both institutions, and from then on, Kumagusu was never again officially admitted to any university or institute.

Copyright reserved MINAKATA KUMAGUSU ARCHIVES (Tanabe City)

After a journey where he collected plants and animals in Florida and Cuba, Kumagusu left for London, the ‘capital of learning’ at that time. In London, Kumagusu completely changed his focus from collecting and studying botanical species in the open air, which had been the main part of his research, to concentrate on the study of folklore and anthropology. This was partly due to the fact that London was not richly vegetated, but above all, because the many museums, including the British Museum, which was a ‘sanctuary of knowledge’ utterly fascinated him. From then on, he published a series of essays in international journals, such as ‘Nature’ in which he published a total of 51 articles. This is a world record for a single individual.

Copyright reserved MINAKATA KUMAGUSU ARCHIVES (Tanabe City)

He was in his element when he was conducting research, but in 1900, Kumagusu was forced to return to Japan, mainly due to financial difficulties. In 1900, he left for ‘home’, after 14 years of study abroad. After returning to Japan, Kumagusu stayed at the foot of Mt. Nachi, where he once again devoted himself to collecting botanical species. From London, the world’s great metropolis and capital of learning, to the solitude of Nachi[1] – at first glance, it seems that Kumagusu had closed his own ‘world’. But this is a big mistake. Kumagusu was actually opening his own world while he secluded himself there.

It is true that life at Nachi was very lonely and solitary. But on the other hand, his inner world was infinitely expanding. For example, in meditation, when one goes deep inside oneself, it leads to a universal place. Just the same as in meditation, Kumagusu read books on deep psychology and Kegon[2] thought, and in the silence of Mt. Nachi, he was deeply confronted with himself. While reading such books describing the universal unconscious and the world beyond the distinction between self and others, his self-consciousness began to expand rapidly. Furthermore, there was one more thing that led him to the universal field, and this was ‘slime mold’. Kumagusu looked at this microscopic organism day and night under his microscope, and saw ‘life itself’ in it. This may have been his own form of meditation with a microscope. Kumagusu left us the following words;[3]

“…Because the soul of each individual entity emerges from Dainichi大日(the cosmic Buddha of Shingon metaphysics: the primordial, fundamental entity of the entire universe)[4], For example, with a single microscope I can look into the large universe beyond the endless universe and the larger universe that envelops them. It is fun for me and this fun never runs out. As if you just buy a microscope and are looking into it, you’ll enjoy doing it all your lifetime.”

(Letter to Horyu Toki, dated July 18, 1903)

In other words, Kumagusu used a microscope and sensed the macrocosm that still encloses the ‘macrocosm’, in the microcosm of slime mold. Observing slime mold with a microscope means, in a sense, to seclude inside oneself, but ‘beyond’ it, in fact, the macrocosm is expanding. The inside extends directly outwards.

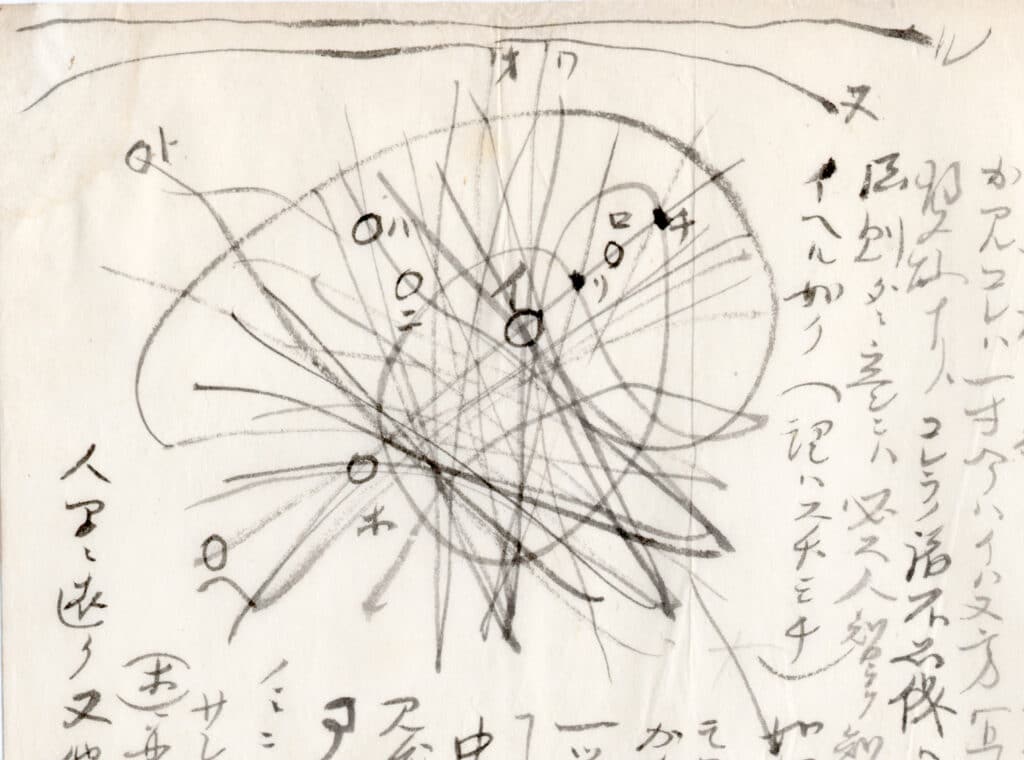

The southern part of the Kii Peninsula used to be called ‘secluded Kii’, which means ‘hidden country’(Komoriku). A place where the gods used to hide themselves (seclusion). In this ‘hidden country’, Kumagusu was secluding himself in the inner and microscopic world, and at the same time he connected to the ‘macrocosm’ where the gods were. During this period, which some researchers call his ‘Nachi-secluded period’, Kumagusu sparked his accumulated knowledge. One of the manifestations is the so-called ‘Minakata Mandala’. Its unusual sketches represent Kumagusu’s own ‘cosmology’. These countless net-like forms are very similar to the amoeboid forms of slime mold. Kumagusu himself did not mention the similarity between his ‘Minakata Mandala’ and the slime mold. However, considering the fact that Kumagusu was very keen on collecting slime mold at that time, and that he used to do ‘meditation with a microscope’, we can be sure that the influence of slime mold was behind the idea of the ‘Minakata Mandala’.

Copyright reserved MINAKATA KUMAGUSU ARCHIVES (Tanabe City)

It seems to be fateful for him, who has the name Kumagusu (‘Kuma’ in Japanese means a ‘bear’ and ‘gusu’ means a ‘camphor tree’), to search for the slime mold which can be described as neither animal nor plant, (or they are both). Three years later, Kumagusu left Nachi to live in Tanabe-town. Of course, he continued his research on slime mold. At this time, he developed his famous ecological movement, that is, ‘The movement opposing the shrine-merger policy’. This is said to have been the initiative behind the ecological movement in Japan. The reason why is that Kumagusu started and became involved with this movement, as described below, the slime mold was actually involved in it to a great extent.

The main reason for Kumagusu’s opposition to the edict is said to have been his indignation at the fact that the precincts of his neighboring Hiyoshi Shrine, in Itoda, had been completely demolished for the merging or eliminating many shrines. In the precincts of that shrine, Kumagusu discovered a very rare new species of slime mold (arcyria glauca) and so it became a monumental place for him. He also defended the nature of Kashima Isle (神島)- a small island in Tanabe Bay with his life, in his campaign against the amalgamation of shrines. The vegetation of this island was and still is as complex as a mandala, and it is a treasure trove of rare animals and plants. Kumagusu often collected and observed slime mold on Kashima Isle. The island, less than 3 hectares in size, was a limitless field of interest for him.

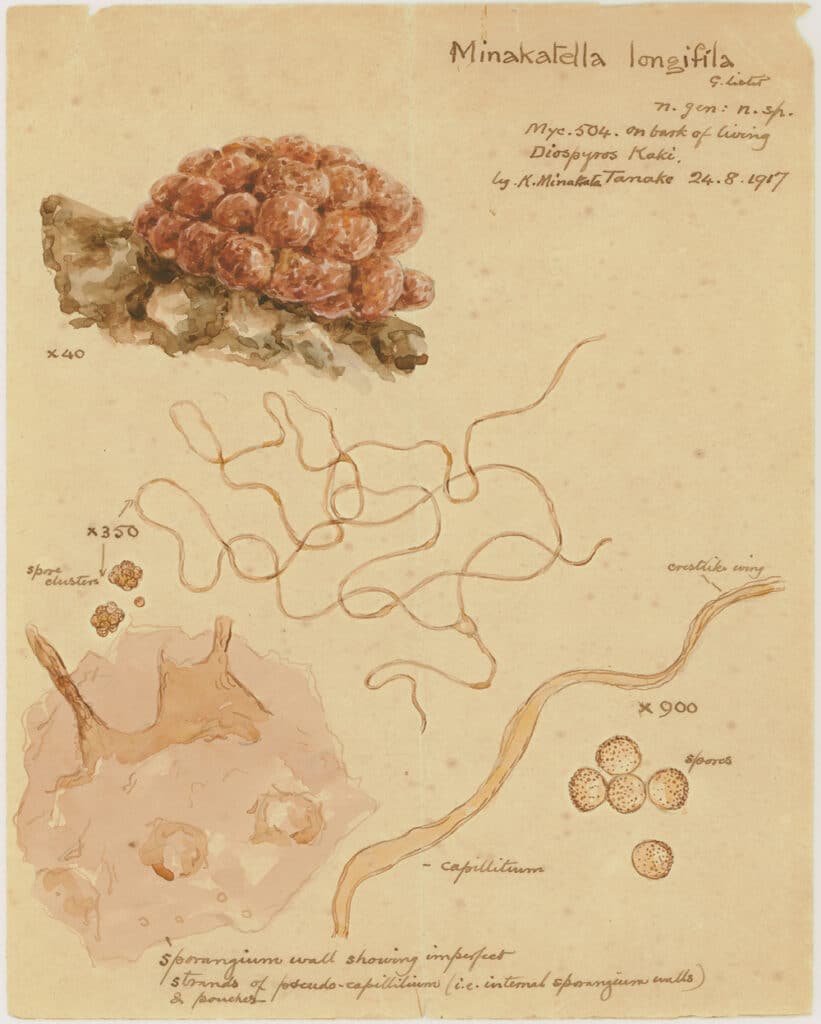

Through slime mold, Kumagusu sensed the ‘macrocosm’ and searched for the fundamentals of life. The garden of his house was also an infinite field of study for him. In fact, Kumagusu discovered the very rare slime mold (Minakatella longifila) in this garden.

Copyright reserved MINAKATA KUMAGUSU ARCHIVES (Tanabe City)

However, Kumagusu’s main aim was not to discover and classify new species of slime mold. He even said that the discovery of new species was just a ‘game’. Kumagusu’s aim was to explore the complexity of life phenomena through slime mold. Through slime mold, he pursued the most fundamental questions, such as ‘what is life, and what is death’.

To find the primordial impulse of life or the breath of life- this quest of Kumagusu is deeply connected with art. It is the role and possibility of art to penetrate deeply into events and to reveal the breath of life hidden in them. In Kumagusu’s words, to empathize deeply with an event is called‘indwelling (直入)’. When we ‘indwell’ with an object, and we are able to gain the ‘something’ which is felt there, or when we see such a ‘something’ in front of us, we are filled with great joy. In other words, it is the experience of feeling that we are surrounded by the ‘macrocosm’.

Kumagusu, who spent the first half of his life moving ‘globally’, hardly ever left his ‘local’ Tanabe-town in the second half. This is because he found in the organisms, especially slime mold, that secluding himself in the ‘local’ is actually to open up to the ‘global’ or even to the ‘macrocosm’.

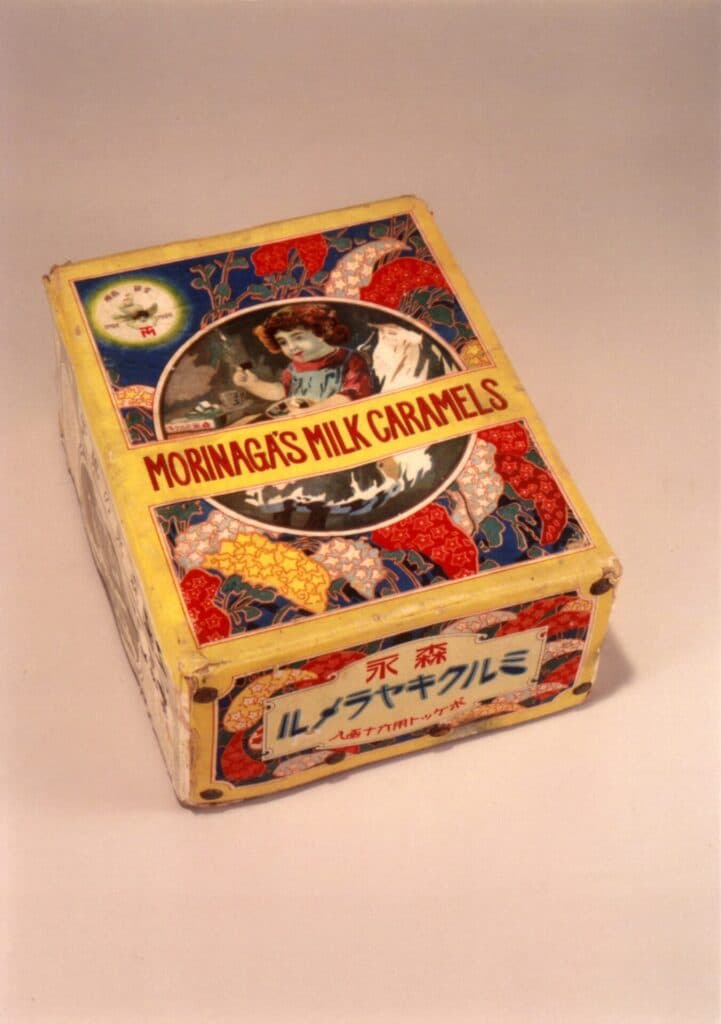

Later on, Kumagusu delivered a lecture to Emperor Hirohito on the rare flora and fauna of Kinan, including slime mold. In fact, Emperor Hirohito was also greatly interested in slime mold and studied it. Kumagusu presented his specimens of slime mold in an empty caramel box. In such a case, a box made of paulownia wood is usually used. The Emperor, however, said to Kumagusu affectionately, “I’m absolutely fine with that.” A ‘friendship’ was born between Emperor Hirohito and Kumagusu that was like a breath of fresh air.

Copyright reserved MINAKATA KUMAGUSU ARCHIVES (Tanabe City)

In 1941, Kumagusu passed away and he now rests in Kozanji Temple, as if he is looking down at his beloved Kashima Island in Tanabe Bay.

.

<Profile>

KARASAWA, Taisuke

Born in Kobe City, Hyogo Prefecture in 1978. Karasawa graduated from the Faculty of Letters, Keio University in March 2002, and completed the doctoral course at the Graduate School of Social Sciences, Waseda University (Ph.D) in July 2012. He was a researcher of the 1st Minakata Kumagusu Research Promotion Project Grant. After working as a Research Fellow of the Japan Society for the Promotion of Science (DC-2 [Philosophy and Ethics]) and as a Research Associate and Assistant Professor at the School of Social Sciences, Waseda University, he is currently an Associate Professor at Akita University of Art, Department of Arts and Roots, and the Graduate School of Transdisciplinary Arts. He specializes in philosophy and cultural anthropology. In particular, he explores the fundamental ‘ways of being’, in which mankind constructs folk customs, religious beliefs and cultures, through the thought of Kumagusu Minakata (1867-1941), an intellectual giant. In recent years, he has been engaged with his research in comparative studies of Kumagusu and artistic thought, as well as the modernistic possibilities of Kegon Buddhist thought. He received the 13th ‘Yasuo Yuasa Book Prize’ in 2019.

[1] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Nachikatsuura

[2] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Avatamsaka_Sutra

[3] Refer to : “Kojiki” by B. H. Chamberlain

[4] Refer to : ’Spirits and Animism in Contemporary Japan’ By Fabio Rambelli (Bloomsbury Publishing)