Orange Collective

An Art Anthropology of Oranges and Humans – After the ‘Orange Mandalas’ Exhibition (Part 1)

1. Is it Possible for Oranges to Transcend Fundamental Principles?

“Growing oranges is fun. However, sometimes it can be frustrating going to the market when prices are unfair.”

local orange farmer

Entering an orange farm in Tanabe, Wakayama Prefecture, there is a wonderful view. In looking at the view from the farm, I wondered if oranges can transcend existing market principles and are not confined by the uniform criteria of shape, size, and sweetness of the fruit called ‘orange’.

In modern times, for an orange to bear fruit, it required not only the natural gifts of sunlight and weather such as rain and wind, but also various factors such as soil that is suitable for growth, the microbes that create the soil, the network of roots that cannot be seen from above ground, and the food chain, among others. However, many of these elements are invisible and have not received attention. Taking into account this invisibility, in Kinan/Kumano, which is known as the Nenokuni – the underground – in Japanese Myth, might it be time to rethink our existence through “Art” and “Enchantment” that transcends language, using the orange as a medium?

In this regard, the Japanese artist Taro Okamoto (1911-1996), in his book “The Mystery of Japan,” that he wrote while traveling the Kumano and Koya Mountains in Wakayama, describes Kumano as “a realm of the real or perhaps the surreal where darkness and mystery prevail [Okamoto 2015: 141].” Along these lines, Japanese anthropologist Shinichi Nakazawa, in writing about the wall paintings of the Rascaux cave, known as “Primordial Art,” noted they were created in “large, deep, and pitch-black caves” [Nakazawa 2006: 5]. One might consider a dark and enclosed area like Kumano and ask: should we consider Kumano as an important place to ponder art?

Taro also writes, “Art must contain the element of a contradiction: ‘showing’ and ‘not showing’ in one expression. This is a dilemma” [Okamoto 2015: 242, 243].” In response to Taro’s words, Japanese anthropologist, Shinichi Nakazawa (1950-) argues that it is possible to call someone an “artist” who continues to think and express passionately in the midst of this chaotic contradiction [Okamoto 2015: 259]. The contradictions between those two demands might be stated as, “Art to open, but which is still closed. Art that aims to reveal, but that is concealed.” This seems to correspond to the theme of Kinan Art Week, “Muro, soulfully inward. Kinan, open to the world.” As the anthropologist Nakazawa claims, if art is defined by two such contradictory natures, Kumano/Kinan and art would be a perfect coalescence. This connection will be further expounded on later by exploring the art anthropological ideas and practices which are connected to art and ethnicity (via methods of cultural anthropology).

Additionally, Emanuele Coccia, an Italian philosopher, defines contemporary art as an exercise that is not regulated by disciplinary rules, but rather cleaves through them. By shaking its assumptions, all of society itself can start to visualize things that could not be imagined, thereby making it possible for culture and society to become different from the status quo [Coccia 2022: 178]. Based on his ideas, we have sought “orange beyond principles” alongside the concept of contemporary art, as well as deeply exploring the underlying element of “a place” that forms the foundation of Coccia’s idea. Our fieldwork has been conducted in local Kinan areas such as Akizu, Haya, and Maro in Tanabe City, Wakayama prefecture.

At the same time, we have started the “Orange Collective” with “orange” as its main theme. By having “orange” as our primary focus, we eliminated the hierarchical orientation humans tend to have, and tried to create an opportunity to view our work through deterritorialization, a non-categorizing perspective. As a result, we received various comments from not only the art field, but also from local people, such as “[it was] more approachable than last year,” “people and oranges could be the same,” “the importance of cultivation while moving,” “I can see art as being more relaxed,” “I can see things in a more critical way,” and “the exhibition itself is art.”

In this article, I will review the contemporary art exhibition “Mikan Mandala,” which was conceptualized by Orange Collective and curated by Production Zomia, a combined team of Japanese and Southeast Asian artists and curators.

(2) Deep and Symmetrical Anthropology of Kinan/Kumano

By integrating the intellectual function known as “symmetry,” which incorporates logical contradictions while performing a general overall operation from the underlying part of the mind (or consciousness), I attempt to re-edit the exercises of the mind that are performed in a wide range of fields, from religion to economics, from science to art, all from a consistent viewpoint [Nakazawa 2006:v].

Now, we are faced with significant economic disparities and imbalanced democracy. We certainly live in an “overwhelmingly asymmetrical world” where human-centered scientific rationality has gone too far. Is this distortion not a remote cause of problems such as the Ukrainian war and the Myanmar coup? I believe that there are many hints in the deeper parts of Kinan/Kumano that may help us reconsider a symmetrical world. These include Taro Okamoto’s mystical thought on Kumano, Japanese biologist Kumagusu Minakata’s Kegon-influenced thought (1867-1941), and the anarchist thought of Kenji Nakagami’s (1946-1992), a Japanese writer related to Wakayama.

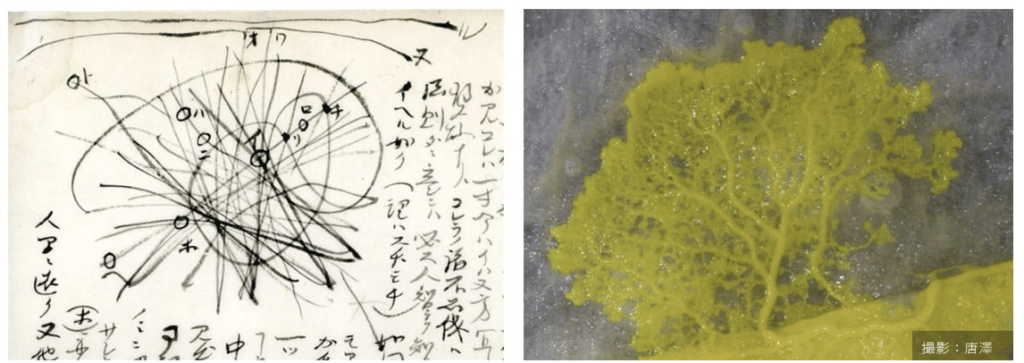

One might in particular look at the “Symmetrical Anthropology” advocated by Shinichi Nakagami and the extension of “Art Anthropology” that was born from it, influenced by the world famous local scholar, Kumagusu Minakata, and Tibetan Buddhism. Minakata, as a biologist, devoted himself to the study of slime molds; as an anthropologist, he developed mythological thinking, while completing his own philosophical ideas based on Kegon Buddhism. Also, he carried out concrete social movements such as the de-integration of Shinto and Buddhism. His engagement in disparate fields is connected to slime molds, as they move freely across the boundary between animals and plants. For myths, it connects heterogeneous things beyond separative thinking. While in Kegon-based Buddhism, he tried to find the cosmic even in small things. According to Nakazawa, “Minakata’s quest is similar to what has been practiced for over a thousand years by people in Tibetan Buddhism” [Naka Zawa 2008: reference 4-6]. In other words, Minakata was able to create a “Minakata Mandala” by conducting a comprehensive thought exercise that maintained a high degree of symmetry.”

A “Mandala” is a geometric figure created in ancient India as a model of the workings of the mind, which was incorporated into Buddhism and has evolved over time. Like “Mikan,” its typical image is characterized by “symmetry,” with four directions emerging from a circle and a square made up of four sides divided into four [Nakazawa 2010: 9]. It was introduced to Japan by Kukai (774-835) and blended with Japanese natural beliefs. There is the “spontaneous mandala” [Nakazawa 2010: 20] that is not even limited to circular shapes, similar to what Kumagusu created in his mandala figure.

Tibetan Buddhism, Mandala and the thought of Taro Okamoto can be thought to overlap. When Taro saw “Ryokai Mandala (Mandala of the Two Realms)” in Koyasan, Wakayama, he said, “It’s unassuming, unattractive, and ignores emotional affects, but at the same time, those elements themselves convey a strong expression. The screen itself is flat and has a submerged calmness, but the imagination that opens up in me through it is vast. And mandalas are said to be an “Enchantment” to discover a “universe in ourselves” [Okamoto 2016: 214, 233, 234]. As Taro said in the movie Taro Okamoto’s Okinawa, “If you don’t live as a cosmic whole, instead of being divided into pieces, there is no purpose in living.” Based on this statement, I believe that the “art” from his perspective is the “enchantment art” of “human beings living as a cosmic whole.”

In this context, we held a screening of the movie “Tower of the Sun (2018)” on October 14th during the exhibition. We invited Prof. Taisuke Karasawa, a philosopher and Minakata Kumagusu researcher who was also in the film, to talk about the connection between Kumagusu Minakata’s slime mold, the mandala and Taro Okamoto’s Tower of the Sun. To this extent, we explored the connection between the “Tower of the Sun” and orchards as both being an offering to the sun. I think that the reversed structure of the “underground sun” and the “tree of life” inside the “tower of the sun” is very important when considering the “relationship between humans and plants” and “the relationship between Amaterasu and Susanoo,” which will be discussed below. I think it is suggestive.

(3) Orange and Art Anthropology

I. Mandarin Oranges on Rice Cakes

So, after a long introduction, we’ll now touch on the main topic of “Orange.” To begin with, why have humans walked together with “citruses”? Why do Japanese people place “Daidai (Bitter Orange)” on rice cakes and decorate their entrances with oranges and shimenawa (the secret rope) during New Years? I’ll leave the answer to your imagination, but it must be deeply connected to the depths of the Japanese “heart.”

“A single piece of paper can express a mysterious color just by being cut with scissors . . . In this way, even things that are simply a promise can move our spiritual life to its core. The excitement can be more strongly tied to life than an elegant artistic expression . . . Shouldn’t we exalt moments that are thought to be non-artistic? In this sense, religious/magical methods and the promise itself is a powerful suggestion.” [Okamoto 2015:199]

In recent years, in the world of art history, the term “reenchantment” has attracted attention. The importance of primordial magic and witchcraft, which would not normally be called a kind of “art,” is being re-evaluated. In that sense, for Japanese people, and for people all over the world, citrus fruit is certainly a ‘non-art’ in our daily life. The Japanese mandarin orange on rice cakes is a kind of silent allusion to what Taro said, and I cannot help but feel that it has the panoramic potential to awaken our spiritual lives from the roots. To better explore this, I have been planning the exhibition by utilizing the mythical thinking of the binary oppositions of “fruit/root” and “Amaterasu/Susanoo.”

II. Orange and Capitalism

Originally, in the West, the fruit “orange” symbolized the sun and prosperity [Laslow 2010: 296, 297]. In Japan, tachibana (the original species of mandarin) also fulfilled the function of supporting the deity of the Sun, Amaterasu, and her lineage [Yabumoto 2022: “The Myth of the Orange”]. However, it seems to us that we are focusing too much on only fruit.

Originally, the word “capitalism” has its roots in Greek, meaning “head” or “tip,” referring to the tip of the pistil in the “fruit” [Nakazawa 1996: 93, 94]. In contrast, the Kumano/Kunigami region is also a place where trees and roots are deeply related (Susano-related?). As shown in the above visual of the exhibition, the idea is to reverse the relationship between “fruit” and “root” and reconsider the meaning of “fruit (capital)” through the illogical and mythical question: “does the root bear fruit – does the fruit take root to grow over?”

III. Pluralization of the Sun

Another perspective is that of the “pluralization of the sun”. What I feel after reading the Kojiki is that Amaterasu carried too heavy a burden. Tetsushi Yamamoto (1948-) states that “天照amaterasu – lighting the sky” is “海照 – amateru- lighting the sea,” and that she was originally not a deity that illuminates the sky, but instead a deity that illuminates the sea [Yamamoto 2022: 270]. Japanese mythology until now has a vertical three-layered structure of ‘高天原,Takamanohara (High heavenly plain)’, ‘葦原中国, Ashihara no Nakatsukuni(Central Land of Reeds)’, and ‘根の国, Ne no Kuni, the underworld.” There is a tendency to think that Amaterasu and her descendants exist at the top of the hierarchy. However, I think it’s time for us to reimagine the world of gods existing horizontally, and in our exhibition, we attempted to find the god of our own “place of belonging”. To that end, we invited Mr. Yamamoto to hold a talk session titled “Mikan Myth – Let’s Know the Gods of Kinan”.

Additionally, in the VR artwork titled “Mikan Myth”, Tanabe Kosuke creates a virtual world where the viewer can experience an upside-down world in which the relationship between the “sun/fruit” and “tree/root” is reversed.

When you press a switch, it transcends the <one> of connection (or one way street) between “human and plant,” and creates a mandala in which <many> connections coexist in multiple ways. I believe that it is necessary to reconsider our country’s kami (god of place) even before the establishment of the Kojiki, and to rethink a principle different from what I call “the big illusion” (industrial society, capitalism, etc.). In other words, we should focus on local gods in the Kinan area such as Tanabe, Akitsu, and Haya.

IV. Orange and Mandala

Next, I would like to talk about the title “Mikan Mandala”. The word orange is, in its etymology, connected to the ancient Indian world that created Tibetan Buddhism and mandalas. Tracing them back in time, oranges are said to have roots in the Indian sub-continent before the division of Melanesia and Australia 4 million years ago, before the human species existed. The word orange comes from the ancient Indian Sanskrit words “naranga” and “narangi”, which are said to mean “inner fragrance” (see Hyman 2016).

On the other hand, the word “mandala” is said to be derived from the Sanskrit word for “circle” [Jung 1991:223], but in Tibetan it is called “dkyil ‘khor”, where “dkyil” means center and “‘khor” means periphery. A mandala has a multi-layered structure that transcends the center and periphery, and performs a multi-dimensional overall movement [Nakazawa 2012: 172, 178, 179]. According to Japanese religious scholar Motohiro Yoritomi (1945-), mandalas are: (1) plural, (2) central, (3) harmonious, (4) open, (5) dynamic, (6) space as a magnetic field. Rather than purifying by eliminating exogenous materials, the mandala embraces heterogeneous elements and presents a world view that integrates the whole based on a higher sense of values. Therefore, at the 1970 Osaka Expo, a mandala was chosen as the symbol. [Yoritomo 2014: 159-163].

On seeing the Ryokai Mandala on Mt. Koya, Taro writes, “When you look into it from a distance, the whole thing rises up like a beautiful carpet.” He also describes it as “a magical medium” or “a clue to enlightenment”. The mandala itself must be something that disappears colorless and transparent at the moment of enlightenment [Okamoto 2015: 215]. In that sense, when I saw “Sculpture on the Log” (Sculpture on the Vase) by Tetsuro Kano (1980-), I fell into the illusion that I was facing a “three dimensional mandala” (though this was not intended by the artist). The works of Kano, who usually picks up trash as a habit, using materials such as collected wood, glass and stones that have accumulated over the years, can be seen as like a “sand mandala” that flies away when the wind blows. From this point of view, isn’t it natural to try to see a transparent “mandala” in a “mandarin orange,” from the vantage of a simple and small life?

V. The universe seen by Tomoo Hirose

Finally, we asked Tomoo Hirose (b. 1963), a main artist of the “Mikan Mandala” exhibition who has discovered new worlds in beans and lemons, to see the whole universe in “Mikan”.

Hirose is based in Milan, and has participated in numerous exhibitions at museums around the world, including in Japan, Asia, and Italy. In addition, he has recently engaged in work that goes beyond existing general art activities. This includes the project called “Sky Project” (Maebashi, ongoing from 2016 to 2035), done to raise awareness for single mothers in society. He exchanged photographs of the sky with single mothers and their children at Maternal and Child Living Support facilities. This is just one example of his work on long term projects like the Sky Project, connecting disjoint parts of society through his art.

The breadth of Hirose’s concept extends from a macro perspective to the entire earth, across countries and seasons, and even into outer space. At the same time, exemplifying Taro’s concept of “The necessity of microcosmos to macrocosmos [Okamoto 2015: 246],” Hirose discovers richness and diversity in daily food life in Italy. Through encounters and dialogues on cross-cultural journeys, he finds a common sense of “little happiness” and the meaning of “being alive.” A major feature of Hirose’s work is that it strongly appeals to the senses of the viewer, being based on the preciousness of quotidian life. This includes works incorporating lemons and spices spread all over the floor, installations that stimulate the senses of sight, smell and taste, photographs of the sky, a “Blue Drawing” where cells seem to grow infinitely. Another set of notable works is the “Bean Cosmos” series, where beans, pasta, etc. ingredients, rounded maps, marbles, gold, etc. float in acrylic resin. Hirose believes that there is a rich world that is often overlooked in the area between things and other smaller things, such as man-made and natural, day and night. He tries to discover this and capture the contradictions and uncertainties that lie deep inside which do not appear on the surface. Heightening the experience, viewers were able to view the world of Hirose’s work from various perspectives and angles while wandering around the three exhibition spaces where his artworks were displayed.

<Reference list>

・Ando, Reiji. “Jomon Theory.” Sakuhinsha. 2022. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Bourriaud, Nicoas. ”Radicant. Pour une esthétique de la globalisation.” Translated by Hironari Takeda. Film Art. 2022.

・Burgat, Florence. “Qu’est-ce qu’une plante ? – Essai sur la vie végétale.” Translated by Yuko Tanaka. Kawakado Shinsha. 2021.

・Coccia, Emanuele. “Plant Life Philosophy: A Mixed Metaphysics.” Keiso Shobo. 2019. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Coccia, Emanuele. “Philosophy of Metamorphose.” Keiso Shobo. 2022. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Fujihara, Tatsushi. “Thoughts on Plants.” Ikinobirubooks, Ikinobirubooks, 6 Sept. 2021. https://ikinobirubooks.jp/series/fujihara-tatsushi/378/.

・Hyman, Clarissa. “Orange History.” Hara Shobo. 2016. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Ingold, Tim. “Living Moves, Knows, Writes” Translated by Tetsushi Nakano, et al. Sayusha. 2021. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Ishikura, Toshiaki & Karasawa, Taisuke. “Anthropology of Viscera and Co-Mutants.” EKRITS, EKRITS, 24 Dec. 2020, https://ekrits.jp/2020/12/3980/. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Jung, Carl Gustav. “Individuation and Mandalas.” Misuzu Shobo, Ltd. 1991. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Miki, Shigeo. “Fetal World.” Chuko Shinsho. 1983. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Montgomery, David & Bikle, Anne. “The Hidden Half of Nature The Microbial Roots of Life and Health.” Translated by Natsumi Katooka. Tsukiji Shokan Publishing., Inc. 2016.

・Mori, Motonao. “Introduction to Anarchism.” Sjolima Shobo. 2017. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Nakazawa, Shinichi. “Gift of Pure Nature.” Serica Syobo, Inc. 1996. [Translated from Japanese.] ・Nakazawa, Shinichi. “Art Anthropology.” Misuzu Shobo, Ltd. 2006. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Nakazawa, Shinichi. “Symmetrical Anthropology,” Kodansha Ltd. 2008. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Nakazawa, Shinichi. “Jung and the Mandala.” Edited by The Japan Association of Jungian Psychology. 2010. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Nakazawa, Shinichi. “Oriental.” Kodansha Gakujyutu Bunko. 2012. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Nakazawa, Shinichi & Ozawa, Minoru. “Dive into the Sea of Haiku.” Kadokawa. 2016.[Translated from Japanese.]

・Mancuso, Stefano & Viola, Alesandra. “Verde Brillante―Senaibilità e Intelligenza del Momd Vegtale.” Translated by Koji Kubo. NHK Publishing, Inc. 2015.

・Okuno, Katsumi et al. “ Anthropology of Humans and Animals.” Shumpusha Publishing. 2012. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Okamoto, Taro. “Mysterious Japan.” Kadokawa Sophia Bunko. 2015. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Pierre Laszlo. “Culture of Citrus Fruits.” Translated by Tomoko Teramachi. Ittosha Incorporated. 2010. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Weil, Simone. “Having Roots (1)” Iwanami Shoten,Publishers. 2010. [Translated from Japanese.] Yabumoto, Yuto. “Orange Collective: From Mikan and Spiritual Traditions in the East, to the Orange in the Global Market.” Kinan Art Week, Kinan Art Week, 21 Feb. 2022, https://kinan-art.jp/en/info/5778/.

・Yabumoto, Yuto. “The Myth of the Orange.” Kinan Art Week, Kinan Art Week, 22 May 2022, https://kinan-art.jp/en/info/6987/.

・Yabumoto, Yuto. “The “Place” of Kinan -Modernism and Animism-.” Official Catalog for Kinan Art Week Exhibition 2021. Kinan Art Week. 2022.

・Yabumoto, Yuto. “Archived Text (First Half) of Kinan Chemistry Session Vol.2 ‘Seclusion and Openness: Kumagusu Minakata, the Giant of Knowledge and Contemporary Art.’” Kinan Art Week, Kinan Art Week, 13 July 2021, https://kinan-art.jp/en/info/937/.

・Yamamoto, Tetsuji. “Kojiki and the Theology of the Country: The Beginning of Japan and Place Myths.” EHESC. 2022. [Translated from Japanese.]

・Yoritomi, Motohiro. “Esotericism and Mandala.” Kodansha Ltd. 2014. [Translated from Japanese.]