Orange Collective

Dialogue: On the Historical Context of HIROSE Satoshi’s “Common Farms”(Part 1)

Dialogue: On the Historical Context of HIROSE Satoshi’s “Common Farms”

Sumitomo: In this column, Kanai Tadashi and I, Sumitomo Fumihiko, will discuss what artist Hirose Satoshi attempted to exhibit during Kinan Art Week 2022. This discussion will refer to the history of art, and will take place in the form of correspondence by email. The title for the overall exhibition was “Orange Mandala,” and it featured nine Asian artists exhibited in three themed venues: “Fruition / A Journey through Fruits,” “Symbiosis with Fungi / Mycorrhizal Networks” and “Soil and Roots / Exploring the Invisible Roots.” Most of the artists are active in Asia, with only Hirose, a Japanese artist, living elsewhere, in Milan.

At the exhibition, Hirose not only presented objects and drawings, but also proposed the idea of creating a “Common Farms” at one of the exhibition venues, Akizuno Yui warehouse. Of note, this venue is jointly funded by local citrus farmers. In addition, Hirose and local Kinan residents have also started “A Journey of Citrus Sapling,” in which participants are invited to grow citrus saplings until a farm land is one day acquired. The project aims to create a “farm” where participants can bring their varied knowledge and experience to the project. It extends Kinan Art Week’s ongoing art project, the Orange Collective, which explores the connections between agriculture, art, philosophy, anthropology, botany and design. This initiative will give us the opportunity to ponder oranges from a variety of angles.

The aim for the project is to attempt to reimagine the current major agricultural practice, which tends to focus on commodity production, as a more cultural practice. Many such works that engage with plants and nature have been exhibited at contemporary art festivals in recent years. I am reminded of the Orange Mandala Exhibition participating artist, Tuan Mami of the Nha San Collective, who ran a farm for Vietnamese immigrants at documenta 15 in Kassel, 2022. Many people are turning their attention to agriculture pressing issues of our time – the climate change crisis, the reexamining of anthropocentrism, the increasing number of people forced to move – and contemporary art and its fieldwork often reflect on the context of those issues.

Further to this, I approached Prof. Kanai, who has researched the Arte Povera (“poor art”) movement that occurred in the 60s and 70s in Italy. The movement is an important historical moment for Hirose, who moved to Italy 30 years ago. Kanai even organized an exhibition of Arte Povera held at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art in Japan in 2005. This exhibition depicted a resistance to ever-expanding capitalism and American pop art by examining the context of the works of Arte Povera artists, which are now enshrined as objects in the exhibition rooms of museums. Since then, as you continue your research on Arte Povera, could you tell us what you are currently interested in, Prof. Kanai?

Kanai: I saw Hirose’s work in Maebashi, Gunma in 2020 and at the Vangi Sculpture Garden Museum, Shizuoka last year and was strongly attracted to the vivid concepts of his art. This year, I was very interested in the Orange Mandala exhibition in the Kinan region, but unfortunately I had to miss it. However, it seems that its cross-cutting and sustainable activities have only just commenced. The commons farm Hirose proposed is fascinating as well. I would also like to see the sky and sea of Kinan, eventually, in the near future.

As regards Hirose’s activities in Kinan, when you look at it from a broad perspective, he has been in close touch with art trends that have been spreading across the world in recent years. He focuses on projects over objects, fieldwork over productions, collectives over individuals, and artistry over art commodities. In many cases, his works raise compelling questions and an awareness of politics, the economy, the environment and human beings, each to varying degrees. While I have not seen it myself in person, these works seem to belong to the same milieu as that of documenta 15. As Sumitomo pointed out, the historical context of such artistic practices should be of great interest. For example, I think that reassessing, or at least confirming, the art of the 1960s as a precursor to such practices is an effective way to critically analyze the current art scene. In terms of the art of the 1960s, in the case of Italy, to which Hirose is closely associated, one such example would be Arte Povera.

It was in 2005 that the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art held the Arte Povera exhibition. The exhibition was linked to the Aichi Expo, with the theme “The Wisdom of Nature,” and with a budget secured, historical works from around 1970 were brought in from museums in Turin and Castello Rivoli, Italy. While the exhibition may have been very object-oriented and “masterpiece” oriented, the exhibition catalog did its best to explain the circumstances in which such works were produced.

The first time I saw Arte Povera’s work in person was at the Venice Biennale in 1995. I was studying there at the time, and the Bosnian conflict was just coming to an end with a large-scale NATO intervention. So, the topic of conversation at the neighborhood bar was either the usual football or the conflict at hand. In particular, the dumping of unused munitions into the Adriatic Sea by US aircraft flying from bases in Italy was a problem that threatened Venice’s industry. The refugee problem was also a political issue in Venice, not far from the conflict zone. The mayor at the time was Massimo Cacciari, who was also a professor of aesthetics at the Architecture Institute of Venice. I believe the influence on Cacciari by the Italian Spinozistic-Marxist sociologist, Antonio “Tori” Negri in the Veneto labor movement was decisive for Venetian politics and culture during this period. Cacciari’s main book, L’Arcipelago (Archipelago), was also written during his time as mayor. The book argues for the coexistence of pluralistic differences without a center or hierarchy. His thoughts, which survived through the year of “1968,” seems to have retained their reverberations in Venice at the end of the 20th century.

To return to the subject, the anti-globalist or, to put it simply, anti-American mood smoldering in Venice in the 1990s must have had some influence on my belated encounter with Arte Povera. In short, I could not miss Arte Povera’s ethos of ’68 while in Venice in 1995. As Sumitomo points out, Arte Povera at the 2005 Toyota exhibition emphasized “resistance to ever-expanding capitalism and American pop art,” I think this is partly due to my personal history, having spent time in Italy, which might have been reflected in the exhibition described above.

Now, before responding to your question further, let me briefly summarize the birth and transformation of Arte Povera here.

The starting point was a September 1967 group exhibition in Genoa curated by the emerging critic Germano Celant. Initially, he defined “Arte Povera” as pure presence without rhetoric, meaning, mimesis or convention. Therefore, a metal pipe is presented as a metal pipe, a clump of dirt as such, and a newspaper as such. It is not that the thing itself was important. Rather, the tautology, the thorough non-representation, that A is A, seems to have been essential. Celant also contrasted Arte Povera to “Arte Ricca (rich art)” from the outset. Pop art in the United States and Great Britain falls into this category. So, to accentuate this point, one can clearly view Arte Povera as a movement against the technological civilization and consumer culture of the United States. The anti-American overtones can indeed be seen in Celant’s article published in Nov.-Dec. of the same year in the contemporary art magazine, Flash Art, in which he described the practices of Arte Povera as guerrilla warfare. Needless to say, this was the era of the Vietnam war.

However, in the following year, 1968, there was a subtle change in Celant’s discourse. Rather than extolling tautology, he speaks of “nomadic behavior” and “intuitively free action,” emphasizing the practical, action-oriented aspect of the works. Alongside this, changes occurred among Arte Povera artists and their works. In 1969, the book “Arte Povera” was published, discussing among other artists, Richard Long, Joseph Beuys and Bruce Naumann. The opening section sets the following tone:

Animals, vegetables and minerals have cropped up in the art world. The artist is attracted by their physical, chemical and biological possibilities. He is renewing his acquaintance with the process of change in nature, not only as living being, but as a producer of magical, wonderful things, too….Like a simple-structured organism, the artist mingles with the environment, he camouflages himself with it. He broadens his threshold of perception and he sets up a new relationship with the world of things. (Germano Celant, Arte Povera, Mazzotta, Milano, 1969, p. 225. English Translation: Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev (ed.), Arte Povera, Phaidon, 1999, p. 198.)

In addition, he argues:

Adapting himself in order not to assimilate himself, he waives his “right of citizenship” and he continuously escapes from his acquired dimension. He abolishes his role as artist, intellectual, painter and sculptor. He learns again to perceive, to feel, to breathe, to walk, to understand, to use himself as a man. (Celant, p. 227. Christov-Bakargiev, p. 199.)

Clearly, Celant is approaching the American Philosopher John Dewey’s idea of art as an integrative experience created from the interaction between man and his environment. He no longer defines the “poverty” of the art works in terms of tautology. In 1969, the action of approaching the environment and the kind of multi-materialism brought about in the process were at the core of Arte Povera.

As for the artists of Arte Povera, after a group exhibition in Munich in 1971, no organized movement ever coalesced. In the end, the act of exhibiting works itself did not fit well with Arte Povera’s practical and experiential orientation. Or perhaps the “Hot Autumn” faded into the “Years of Lead,” and in Italy’s social climate, which was also economically in recession, it may be that the artistic practices that advocated experimentation, freedom and change had lost their luster. It was around the time that Trans-Avanguardia eventually emerged.

Arte Povera would once again attract attention about 10 years later, at the Pompidou Center with “Italian Identity” (1981), and at Turin with “Coerenza in coerenza (Coherence in Coherence): From Arte Povera to 1984.” By that time, Arte Povera works were also physically displayed as exhibition artworks and introduced as a piece of Italian 20th century art history, even being collected and purchased. This commoditizing process may be similar to that undergone by many conceptual art works.

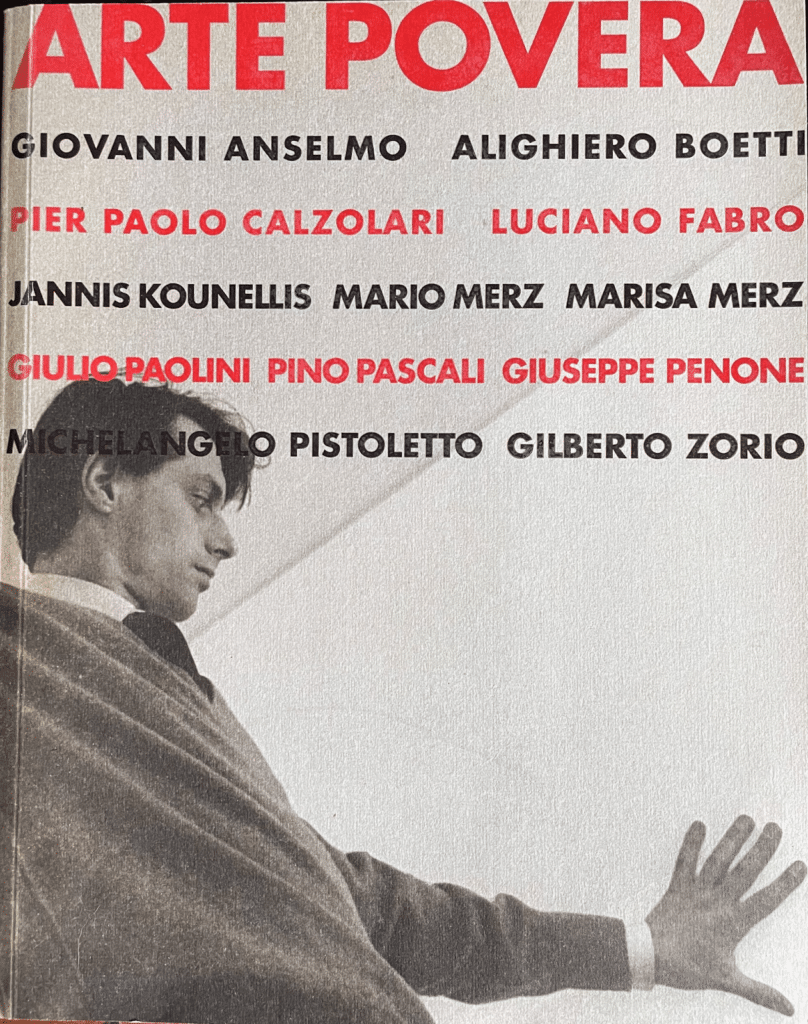

Following the above history, if we trace the trajectory of Arte Povera, we can clearly see the convergence from trial to action, then to artwork, and finally to object. However, we should not fail to note that this history has been retrospectively arranged and edited since the 1980s, with a specific emphasis on the physical works. It should also not be forgotten that the 12 artists, namely Anselmo, Boetti, Calzolari, Fabro, Kounellis, Mario and Marisa Merz, Paolini, Pascali, Penone, Pistoletto, and Zorio (like the Twelve Apostles) – were roughly consolidated only around that time period. In other words, the Arte Povera canonized in contemporary art history would have had a considerable number of externals, exceptions and variations. Rather, I believe that it is the relationship with these “external sources” that has actually governed the “canonical” Arte Povera. And it is in the discrepancies and contradictions of this plural form of Arte Povera (or so to speak, Arti Povere) in which there is a strong resonance with contemporary art, and by extension, an element that overlaps with Hirose’s practice. With this in mind, I would like to explore Arte Povera in a broader sense, as well as the exhibitions and practices that had been carried out alongside Arte Povera, but that might be a bit of a long story. Let me stop here for now.

Sumitomo: The political atmosphere that Prof. Kanai breathed in Venice in 1995 – when NATO was repeatedly conducting bombing campaigns in the Bosnian war – reminds one of Arte Povera’s link to protests against the Vietnam War and the protest movement against capitalism. That experience made you pay attention to features that had been overlooked when understood solely through the present-day, exhibited works. Additionally, perhaps your subsequent experience working as a curator dealing with objects in museums might also lead you to cast doubt on the systems that determine what is canonical and what is apocryphal. Furthermore, I also feel that the relationship with the apocryphal actually might have governed the canonical texts. From this astonishing point of view, it would be very interesting to see an image of a plural “Arti Pauvere” you could draw.

Italy is not limited to Cacciari, but ideas such as decentralization and the coexistence of differences appear everywhere in art and culture, and this is felt as a lightness rather than a heaviness of vertical conceptual thinking, which I find very appealing. In conversation with Hirose, an Italian writer and journalist, Italo Calvino’s name often appears. Perhaps it is this influence that leads to the ‘clarity’ of his work. For example, in one work in which a glass or stone sphere is simply placed on a leaf, eventually, as the water of the platanus leaf drains away, the sphere appears to be encircled by a large palm. It is a work in which minerals and plants of completely different textures are placed together without artifice, yet the process creates a work imparting a pleasing clarity.

In the case of works that could be said to consist merely of objects placed where they are placed, Celant described Pop Art, and its social context, as being “Arte Ricca,” whereas, to him, works that showed a clear identity through the tautology that A is A were “Arte Povera.” But what was the intention behind this contrast? Celant’s “Animals, plants and minerals are rising en masse in the world of art” is a very striking statement that declares the coexistence of differences. Does it mean that the animals, vegetables and minerals were claiming a state of belonging to nothing but themselves and of not being named by anyone?

I was keen to ask Prof. Kanai how we could understand the reasons for the transformation of Celant’s discourse from one of tautological interpretation to one extolling nomadic practice and integrative experience. Is the approach to the environment and the emphasis on experience and action really a transition, or should we see the germination of the new aesthetic having already sprouted in the tautological works?

In 1969, Swiss curator Harald Szeemann presented ‘Live in Your Head: When Attitude Becomes Form’ (Kunsthalle Bern), and artists from Alte Povera joined to work with the American minimalist artist, Carl Andre, the American sculptor, conceptual artist Robert Morris, and an English sculptor, Richard Long. Ultimately, in conceptual art, it is the material and documentation that is exhibited, although it is often pointed out that the actual presentation of the work contradicts its artistic philosophy. Many works are sold in galleries and are considered “masterpieces,” and the artists are called “masters.” The American art critic and curator Lucy R. Lippard pointed out this contradiction in her 1973 publication “Six Years: the Dematerialisation of the Art Object from 1966 to 1972,” a chronological record of trends in conceptual art.

However, in addition to this, it is also important to assume that Lippard was more oriented towards action and experience in conceptual Art, in which the discourse on surviving works of art has been more “conceptually” oriented and has played the role of an intellectual critique of institutions. “The Dematerialization of Art” (co-authored with John Chandler), published in Art International vol.12 in February 1968, uses terms such as “ultra conceptual art” and “highly conceptual art.” The use of these terms in the article hinted at expectations for the progress of dematerialization in future developments. Incidentally, the specific artists mentioned were Michael Snow, a Canadian visual artist, and John Cage, an American music composer. Later, Lippard clearly states that she was “politicized” when she traveled to Argentina in the fall of the same year. She posits that the work of art itself does not have to be overtly political, but “the way artists handle their art, where they make it, the chances they get to make it, how they are going to let it out, and to whom” are all connected to the artist’s lifestyle and political situation (p.8). Since 1969, she has been holding exhibitions (known as ‘Number Shows’, titled after the population of the city where they were held). In a preface to the third of these exhibitions, “2,972,453,” and the fourth, “c. 7,500,” which was added in 1997 to Six Years, Lippard states:

The inexpensive, ephemeral, unintimidating character of the Conceptual mediums themselves(video, performance, photography, narrative, text, actions) encouraged women to participate, to move through this crack drilled in the art world’s walls. With the public introduction of young women artists into Conceptual art, a number of new subjects and approaches appeared: narrative, role-playing, guise and disguise, bodies and beauty issues, a focus on fragmentation, interrelationships, autobiography, performance, daily life, and, of course, on feminist politics. (Lucy R. Lippard, Six Years: the dematerialisation of the art object from 1966 to 1972… , 1973/2001, University of California Press, p.xi)

Artists participating in these exhibitions included Adrian Piper, Nancy Holt, Eleanor Antin, Jennifer Bartlett and Laurie Anderson. It is clear that the works are quite different from the reductive forms of Sol LeWitt, Carl Andre, Douglas Huebler and Lawrence Weiner. At the very least, it seems to me that she presented apocryphal showings that differed from the artworks we consider canonical today. I have a feeling that museums and academia have ignored this idea advanced by Lippard and have subsumed conceptual art within reductive forms. It may be possible to find multiple histories here as well.

What was the change that took place in 1968 for Lippard? It seems fair to assume that her experience in Argentina played a major role. In any case, in early 1968, Lippard, who had presented the dematerialisation of art as abstract and process-oriented, could be said to have steered her work towards a more extended range of possibilities. This tendency to focus on action and experience in art emerged at the same time as in Italy.

Kanai: For the moment, let’s continue from my previous correspondence. Arte Povera had been putting forward the non-representational nature of symbols and objects from the very beginning of the movement. Yet, it cannot be overlooked that there were experiments with an emphasis on action and practice happening contemporaneously. Take, for example, the three-person exhibition Arte Abitabile, held at the Sperone Gallery in Turin in 1966. Michelangelo Pistoletto, Piero Giraldi and Gianni Piacentino brought in objects that could hardly be considered aesthetically pleasing, that looked like interior decorations and furniture. It was seemingly lacking or incomplete as an exhibition, but became a place where visitors could behave freely, as if they were inhabiting (abitabile) the venue. Evidence for Pistoletto’s interest in “participation” and “collaboration” continued at his solo exhibition the following year. On the first day, he placed one of his own works in the gallery and freely left it out for any visitors who wished to collaborate with him on it. The same idea could be connected to Pistoletto’s work that was turned into an independent exhibition at the 1968 Venice Biennale. It was like another Salon des Indépendants where all who came were welcome. In another sense, though in the midst of the May Revolution, he utilized his experience and skills to create an open space for liberal dialogue – for which there is a continuous long standing practice – rather than a simple, crude rebellious gesture such as boycotting or occupation.

Also in 1968, in conjunction with the Arte Povera exhibition, the Azioni Povere (Poor Actions) was held in Amalfi. The event was organized by the young Marcello Rumma, a vigorous supporter of contemporary art at the time, and, like Arte Povera, was curated by Celant. Pistoletto and his theatrical group Zoo performed street acts and tailored a procession reminiscent of folk rituals, with Richard Long continuously shaking hands with passers-by. Some of the artists also started playing football with Emilio Prini in the exhibition hall, Annemarie Sauzeau and her friends lay on the beach, while some children played with Pascali’s work. This inclination towards action, the lifting of the boundary between art and life, and the interest in – and will to – communality are, of course, also linked to the political and social circumstances of the time. The organizer Rumma seems to have been quite aware of the artists’ freedom of action. In fact, he took part in the Venice Biennale venue occupation. The debate held in conjunction with the event focused on the political value of artistic production. The artist-critic connections at this time flowed into two important exhibitions in the following year, 1969: “Op Losse Schroeven” in Amsterdam and “When Attitudes Become Form” in Bern.

Now, let’s clear up a few things. In response to your question, it is certainly true that the dichotomy between Celant’s Arte Povera and Arte Ricca is based on an aversion to the hegemony of the United States. Yet, there is also a strong orientation towards directness. It is a consciousness that rejects the complexity and connection to the richesse of reproduced representations. This might be thought of as an impulse towards anti-spectacle or anti-image. Initially, it appeared in tautological works, which later took the form of direct presentations of organic and inorganic objects. In the sense that the hierarchy between the operating subject (the artist) and the object (the material) is not taken for granted, I could see a closeness to the ontology of today’s art. As Sumitomo mentioned, it seems to aim for “a state in which animals, vegetables and minerals do not belong to anything other than themselves and can not be named by anyone.” And alongside this, with Azioni Povere, direct actions were also practiced and experiences were shared directly. Now, it seems that there was a certain logic behind Celant’s discursive transformation towards extolling immediacy, but the truth is not clear. Rather, it seems that it could be viewed as similar to riding a good wave, and I think that is fine with me.

In relation to Hirose, the range that Arte Povera + Arti Povere possessed overlaps well with the breadth of his work, its “clarity” as objects, its practice-orientation and collaborative nature. I think it would be fair to say that they are in sync with the diverse and fascinating ‘poor art’ that only Hirose, who has been observing Italy from the inside for a long time, could create.

It is notable that you mentioned Lucy R. Lippard. Her stance was to talk about the expansion of conceptual art by emphasizing the actions and experiences of the artists themselves, without reducing them to the form or concepts of their works. This is important in reexamining, or rather, deconstructing the Italian artists of the 60s and 70s. In “Six Years: The Dematerialisation of Art from 1966 to 1972,” Lippard writes about the Arte Povera group, specifically focusing on Pistoletto, Alighiero Boetti and the pillar of the group, Mario Merz.

The Boetti’s work featured in Lippard’s book is Twins (a 1968 photomontage double/self-portrait of two identical Boetti surreally holding hands). However, Boetti’s works became more decentralized and deterritorialized in 1971. For one, he began signing his name as Alighiero e Boetti, with an extra “e” (“and”) between the first name and the surname in order to divide the “I.” And then, Boetti discovered Afghanistan. From 1971 until the Soviet invasion in 1979, Boetti traveled back and forth between Italy and Afghanistan, while running a hotel in Kabul, called The One Hotel. It was also around this time that the production of his masterpiece, the map tapestry, Map of the World (Boetti himself was not involved in its production. He entrusted the colors and detailed designs to the site). After the invasion, he was able to continue working from his base in the Peshawar camp.

As a matter of fact, it is a bit of a subtle and difficult question, whether Boetti’s “management” or “ordering” could be regarded as a practice aiming to build a horizontal collaborative relationship with others. I do not think we should understand the “project” too generously from the perspective of contemporary art. However, if we were to ask whether it was one-sided exploitation by a white man, that is not the case. Recent research has shown that it was no doubt a place of cross-cultural exchange and a fecund site for the creation of contemporary art. Of course, I am not talking about altruism or the public interest. The de-centred moment pushed him outwards, and in every case there was a connection that could not be described as horizontal or vertical.

It has been ten years since Mario García Torres, a Latin American artist, picked up the legacy of One Hotel at documenta 13. It was an unforgettable piece for me. At that time, the forecourt of the main venue, the Fridericianum Museum, was transformed into a tent village for anti-globalists which was strangely but systematically organized. It existed in a veritable state of “ordine e disordine (order and disorder),” a term of which Boetti was very fond.

It is not easy to analyze and evaluate Boetti’s practice. At the same time, it contains many hints for thinking about contemporary art practice today. I have largely retired from Arte Povera research, except for Boetti, though I continuously pay attention to new scholarship on it.

KANAI Tadashi, professor at Shinshu University

Born in Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan in 1968. After working as a curator at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art (2000-2007), he has been Professor at the Faculty of Humanities, Shinshu University since 2007. His curatorial exhibitions include Arte Povera (Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, 2005), Vanishing Points (National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, 2007), Aichi Triennale 2016 (co-curated by Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, and etc., 2016). He has also authored Trans-Figurations: Sculpture and Photography in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (AKAAKA Art Publishing, Inc., 2022), co-authored Exploration of the Imaginary 1 The Anatomy of Sculpture: From Donatello to Canova (Arina Shobo, 2010), and co-translated Art Since 1900 (Tokyo Shoseki Co., Ltd, 2019), etc.

SUMITOMO Fumihiko, curator/ professor at Graduate School of Global Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts. Director of Arts Maebashi from 2013 to 2021, where he curated Listening: Resonant Worlds (2020), The Ecology of Expression – Remaking Our Relations with the World (2019) and Foodscape: We Are What We Eat (2016). He curated Demarcation: Akira Takayama / Meiro Koizumi (Maison Hermès Le Forum, 2015), and co-curated Post Nature: Dear Nature (Ulsan Art Museum, 2022), Aichi Triennale 2013, Media City Seoul 2010. As a senior curator at Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo (MOT), he curated the exhibition Tadashi Kawamata: Walkway (2008). He is co-editor of From Postwar to Postmodern, Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (Museum of Modern Art New York / Duke University Press, 2012) and a founding member of Arts Initiative Tokyo (AIT).

Editor/Translation: YABUMOTO, Yuto

Translation: YAMAMOTO, Reiko

Localization: STRUCK-MARCELL, Andrew