Orange Collective

Dialogue: On the Historical Context of HIROSE Satoshi’s “Common Farms”(Part 2)

Sumitomo: The story of Arte Abitabile reminds me of one of Hirose’s projects, which was similar to the Common Farms idea. It was conducted in Sapporo in 1996, after the bursting of the bubble economy, and was entitled “Lived Land.” This work also involved working with the land, including the setting up of a simple stage on a piece of land that had been left vacant, holding performances and workshops on it. There was also a café where discussions were held and tents were lined up in which people could sleep. In addition, the gallery exhibition held at the same time seems to have stimulated the senses of visitors with smells and colors.《Mar Rosso (Knot-hole)/Project A.P.O.》, which was presented in the same year at the Sagacho Exhibit Space, had a commons element to it, in that it also created a place for visitors to spend their time freely on a large carpet, allowing them to carry out activities and to even sleep on the rooftop.

(Sagacho Exhibit Space, 1998), Photo: Tartaruga, Courtesy: Sagacho Exhibit Space

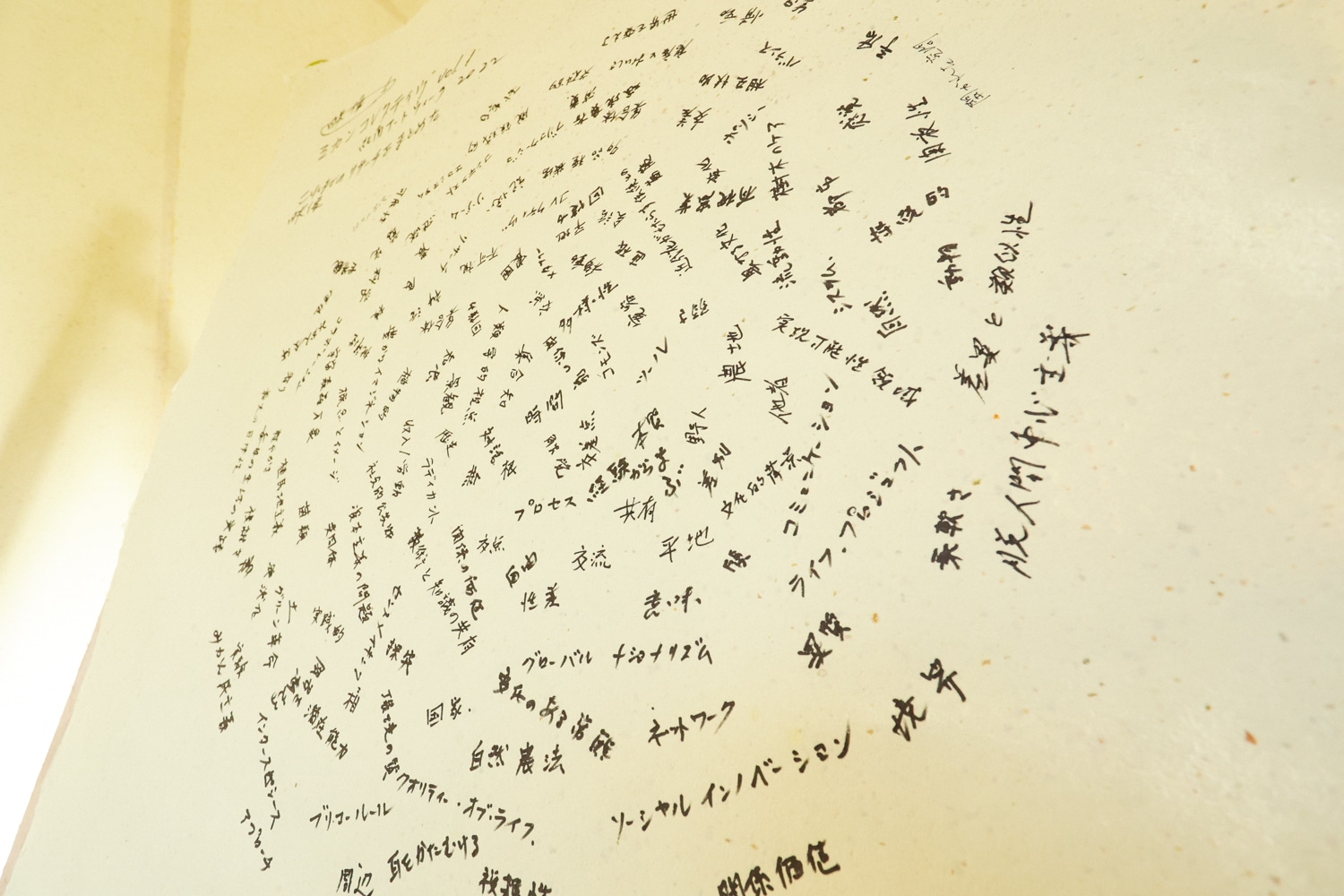

As you point out, the characteristic of being oriented towards practice rather than materiality led to Azioni Povere in Amalfi, but the artists of Arte Povera do not seem to have been actively involved in a political movement. It seems that the critics and artists sought to emphasize action rather than objects, aiming to stimulate the viewer’s perception through actions that work to further the community or collective. Hirose’s exhibition at the Orange Mandala utilized a warehouse shared by local farmers, which was used to place objects for viewers to enjoy the citrus smell and color. At the same venue, Journey of Citrus Saplings was started, in which Hirose presented a proposal to create a new farm in the local area. Compared to the Italian predecessors and Sagacho, whose works were characterized by more gradual actions, this project seems to be characterized by direct action in response to the challenges facing agriculture and society.

Documenta 13 was organized by Carolyn Christov-Bakargiev, director of Castello di Rivoli, which has a large collection of Arte Povera’s works, and indeed, Boetti’s work played a symbolic role. It was a splendid exhibition, filled with the joy of deciphering the history in the relationships between the works on display. However, I think there is an interesting contrast between this legacy and the tent villages of the anti-globalisation movement you have mentioned. In other words, there must have been those who appealed directly to the rectification of inequality through action against “richness (Ricca)” in art.

In this respect, documenta 15 was exactly the kind of project that filled the exhibition room with voices calling out in solidarity with the anti-globalisation movement and other people in marginalized and unstable situations. It is a phenomenon that seems to have reversed the outside and the inside of the Fridericianum Museum. A number of people, like Jason Farago, an art writer of the New York Times felt that they had been placed on the outside. He criticized the exhibition, not only for its art, but also, seeing it as arising from an inward-looking attitude among his peer friends (and enemies), and linking it to the outbreak of Jewish ethnic discrimination. However, in my opinion, this documenta was not as complacent and ignorant of the public as Farago claimed, rather it was the opposite.

This documenta 15 had an ‘easy read’ page on the website, which used plain language to simplify communication. There was also a gallery that communicated its concepts to children. In fact, there was even a day-care center in the museum, which was actually used by a very large number of people, and there were many elements of plant gardening and street culture, which I feel made the exhibition accessible to a wide range of people, not just art lovers. And in the exhibition room occupied by Taring Padi, whose work had been criticized as anti-semitic, the artist gave a gallery tour with a German interpreter, and I saw enthusiastic local visitors applauding at the end of the tour. However, some visitors who simply want to enjoy the work with their knowledge of art may have felt unnecessarily pushed away.

At the same time,I also did not think that the exhibition was disconnected from the history of art. In particular, I felt that we should focus on the media that supported expression. There were only a few paintings and sculptures, but an overwhelming number of videos and photographs, as well as text and sound. In videos, in archive materials, and in hand-crafted-feel DIY constructions, I encountered striking phrases here and there in voice and text. They all had one thing in common: they could be made without academic training, without technical sophistication, without expensive materials and equipment. This seems to overlap with the characteristics of, as Lippard describes, “an inexpensive, ephemeral, non-oppressive conceptual medium.”

Documenta 15 was attended by a number of artists from the non-Western world, known as the Global South. Looking more closely at this, we may need to re-evaluate the Global Conceptualism exhibition organized by the Queens Museum of Art in 1999. Bearing in mind Lippard’s experience in Argentina and the inclusion of many female artists in the second half of the “Number Show,” this was a very important project that did not universalize the artistic movement that took place in New York, but rather saw the potential of conceptual art in a broader sense as being related to local society and culture. Incidentally, Lippard later left New York and moved to New Mexico, where she continued to write with strong enthusiasm about the role of art in the civic movement to acknowledge the diversity of indigenous cultures, in energy and environmental issues, as well as in the relationship between nature, humans and other living things. Thus, I would imagine that the path in which her thought evolved is connected to the thinking that led to documenta 15. However, I do not believe that documenta 15 in and of itself was a legitimate work of conceptual art. Yet, I could see the possibility of a critique that obliquely traverses history and geography alongside Lippard’s thought.

Now, to return to the topic of Kinan and the Orange Mandala exhibition, with this year’s documenta as an example of minorities – like those from the Global South in the western world – being forced into precarious positions as the result of capitalism and globalization. This includes people, and even non-human living organisms, whose natural environment and security are being destroyed and endangered. From this perspective, the problem is caused by the fact that the power of secondary and tertiary industries is greatly outstripping that of primary industries. Activities such as agriculture, forestry and fishing, which support our most basic livelihoods, are losing their practitioners and successors, mainly due to conservative village customs and the burden of physical labor. These have repressed sexual minorities and people with disabilities and led to the exploitation of cheap labor. On the other hand, these circumstances offer many opportunities to reconsider the wisdom of indigenous peoples, and their deep engagement with nature and anthropocentrism, which is an important activity in considering what kind of society we should build in the future. In the catalog of the Global Conceptualism exhibition, I was curious to note that Apinan Poshyananda of Thailand wrote that conceptual art is healing. However, I was not sure if this was true conceptual art, because I do not see how tautological, reductionist art could produce an effect like healing. However, his text points out that for Asian artists who felt discomfort with the universalism of art academism influenced by colonial rule, conceptual art opened up an opportunity for them to find a connection between coeval art and their own regional culture. This is something I think is quite important in understanding Asian art today. I believe that it is linked to civil movements to restore cultural diversity that had been suppressed by colonial rule and the subsequent Cold War regime, as well as resistance to various forms of discrimination. Among them, there were many artists who turned their attention to agriculture and traditional culture, like the group that participated in this year’s documenta. I think that media that is accessible to everyone has given these artists the possibility to express themselves through such activities.

In the West, where literature and music were considered important arts, there seems to have been a hierarchy that emphasized the abstract abilities to handle words and numbers, and regarded manual labor as beneath them. For example, Carolyn Korsmeyer, an author and Professor of Philosophy at the University of Buffalo in New York, and others superimposed onto this history the low regard for the role of women in making handicrafts and crafts. In contrast, restoring the role of the body may also be the aim of the critical work of Azioni Povere and Lippard, as well as that of agricultural and artistic practices.

It is also very interesting that you pointed out Boetti’s tendencies towards decentralization and deterritorialization in his work, Twins, and in his signature. I wonder whether he would see this as a division of the “I” and whether it could be connected to his activities running the One Hotel and in creating other works. Certainly, I think it is different from contemporary artists who initiate projects, but it seems to me that everything he was doing was oriented towards de-centering.

In the 1960s, the American painter Allan Kaprow began to use the term “environment,” emphasizing the point that the work is not self-controlled, but rather a continuous set of coincident happenings within its surrounding environment. He also advocated a method where the expressive subject is not in control. This occurred at the same time as Arte Abitabile. It can be said that such developments raised questions about philosophies of modern art which had strongly assumed the autonomy of individuals, artists, and works. Looking back at globalization since the 1980s, I believe that free and autonomous behaving individuals are well suited to the competition-fuelled neoliberal economy, which has been increasingly debilitating to those in a vulnerable position. documenta 15 called for solidarity by calling them “friends,” because of the historical background of caring for those in such vulnerable positions. People who have been hurt by varied forms of discrimination are healed by engaging with multiple people who were in similar circumstances, and then individuals can be healed, finding friends. On the other hand, in the 1970s, Italy entered the “Lead Age” of intense ideological confrontation. Considering the backdrop of the era, it is easy to understand why Boetti built his hotel in Kabul. Even though the ethnic affirmative action of the 1960s was often accompanied by violence, in Kassel, 50 years later, people engaged in minority rights called for solidarity, using not only visual expressions but also words and sounds. Through the action of decentralization, I saw the possibilities for change in our times.

Prof. Kanai, you have conducted detailed research on the Arte Povera artists and society around 1968. Now that more than 50 years have passed since then, what kind of relationship do you think exists between the present times and in this past movement regarding engaging with pressing social issues, and the practice of artists?

Kanai: I read about documenta 15 and the issue of media with great interest. Indeed, it is very important to take Lippard, and especially her activities after her trip to Argentina, into account when looking at global conceptualism and documenta 15. I regret not going to Kassel this year. I was discouraged by the volume and content of the press coverage, which made me rather cynical. So, I skipped it this time and instead went to the unpopular 59th Venice Biennale, which was also a mistake. I spent too much time in Venice.

Now, let’s talk about the relationship between social issues and art practice. It is well known that art practice emphasizing relationships with society or communities is attracting a great deal of attention in place of the veiled or abstract conceptual art of the past. In this context, the concept of time-specificity has also become prominent. This is a practice/tactic of timing and resourcefulness that is in opposition to the site-specific art of the past, which has often been called “land art” by male artists. Impact, effectiveness and the power of influence are key facets of this work. In other words, they are easy to understand. The practice can also be a political tool. It seems to lead us to a modern view of art, which is very contemporary, though on the other hand, the closest example to this I can think of is actually found in 17th century Baroque art, for example, Caravaggio’s directness. The style has its origins in the Catholic Reformation (Controforma) of the 16th century, with its emphasis on veneration through sacred images. As Frank Stella, the American artist, said, it is painting that directly affects the viewer. It is a realism that instantly engages. Of course, it is not the case that The Supper at Emmaus and Tania Bruguera’s performance art bringing two mounted police inside the Tate Gallery are similarly realistic, but in both cases the participation of the viewer is key, and it is not difficult to describe the experience. In that sense, they are open to all. This is a very interesting link to me, as the old and new Latin worlds seem to be meeting together outside the rules of modern aesthetics and the Western modern avant-garde, which are founded on aesthetic detachment.

By the way, there are ways of dealing with time in contemporary art that do not interweave worldly affairs in the form of time-specificity but, on the contrary, open it up even further. As for conceptualists, On Kawara, a Japanese conceptual artist based in NY, bringing cosmic time to a human scale and Yutaka Matsuzawa, a pioneer Japanese conceptual artist immediately come to mind. As regards Arte Povera, I would point out Giuseppe Penone as one artist who handles time uniquely. Since 1968, Penone has presented a series of sculptures that touch on the time layers of non-human and inanimate objects, such as the growth of trees, the formation of marble and the erosion of rocks by rivers. According to Didi-Huberman’s theory of Penone, this is an interest in “natura naturans (Nature naturing)” rather than “natura naturata (Nature natured, or Nature already created).” It could be said that living and inanimate objects are agents. Penone himself says: “what I am creating in sculpture is something that is not a cultural product.”

The Italian word for sculpture is scultura. My favorite bit of wordplay is thinking of scultura as s-cultura. The prefix “s” can mean separation, exclusion and/or reversal. So, in other words, sculpture is outside “cultura (culture),” and it can be said that Penone is right. However, it is not the case that Penone’s sculpture works fit exclusively outside of culture, for instance: his recent garden activities, such as The Garden of Fluid Sculptures (2003-07), a long-term experiment focusing on the gap between “cultura” and “scultura.” In another work, Potatoes, from the 1970s, where in addition to the early Penone interest in the body, there is a process of almost agricultural-soil-cultural “agricultura.” In the project, he simply grows potatoes. It is a surprise that Penone has continued to work for half a century exploring the larger flow and cycles of time, making works which, while creating a certain mystery, can still be connected to the ecological concerns of his time. Or rather, they can now be connected once again, which is surprising to me. His output consists of a slowness that is the exact opposite of the practice/tactics of timeliness and resourcefulness, yet there must also be another kind of time-specificity in his work, as well. I think Hirose’s activities in Kinan are also connected to these themes, and I would like to ask Hirose about this.

Sumitomo: The history of how the tactics of timeliness and resourcefulness have been used in opposition to modernist aesthetics, and its constituent aesthetic detachment, is indeed interesting. The emphasis on the strength of personal experience for proselytizing, reform and political practice is a method that can be seen in every age. At the same time, your mentioning works that touch on inanimate time was very suggestive, as it seems to be the opposite of time-specificity. Prof. Kanai pointed out that through Penone’s activities, the two are not in opposition, but rather seem to pierce the vast flow of time, which has a connection to our immediate, present-day challenges, such as ecological concerns. If one puts the two in together, there is a danger that changes over a long period of time could be perceived as unrelated to an individual’s limited time. Thus, it is important to try to bridge the gap between the two and make people feel a sense of continuity, and it is tempting to hope that we can expect art to play this role. Perhaps, the reason Penone dared to say, “it is not a cultural product,” was that he was trying to see it as something beyond the culture of human activity.

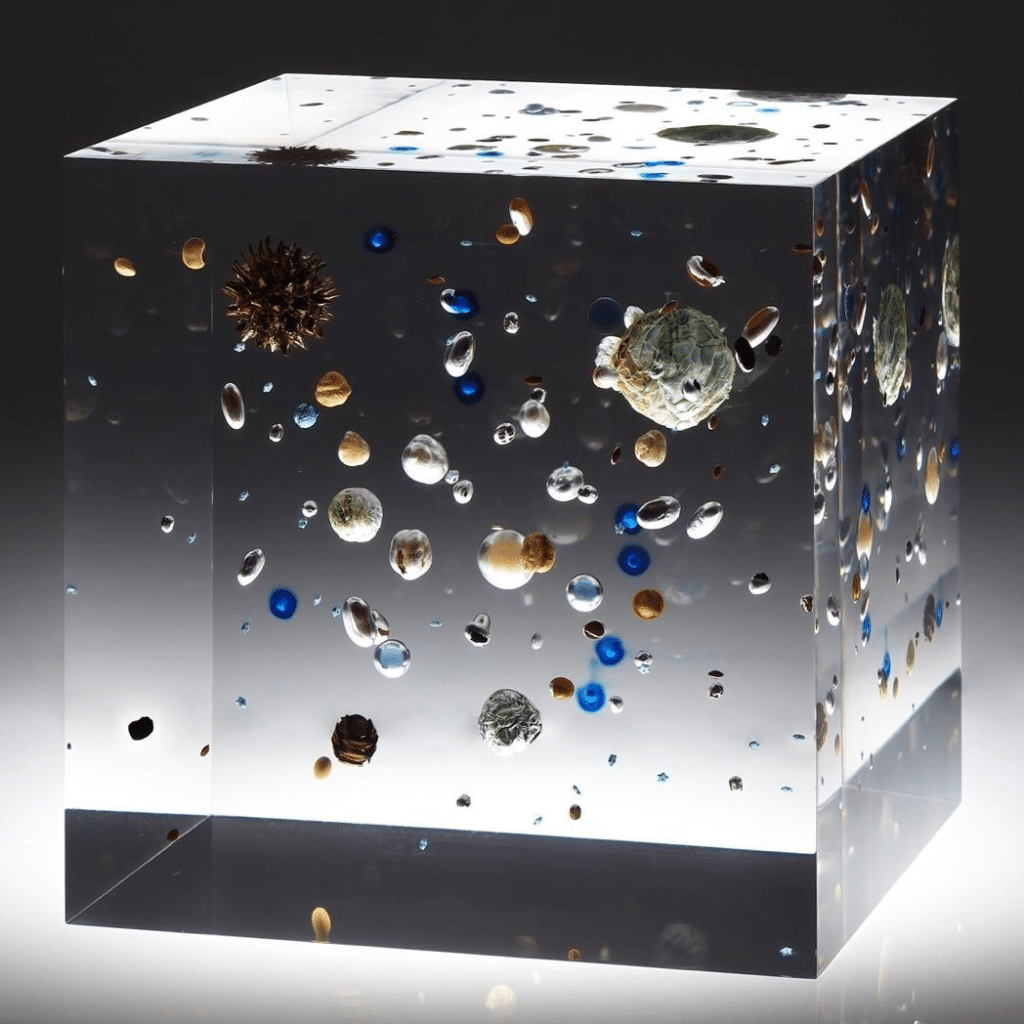

This method of capturing time can be found throughout Hirose’s work: various beans, rolled maps and minerals are trapped in acrylic resin and look like stars in the universe in Bean’s Cosmos. In addition, I would note his long-running series of photographs of the sky. There are both transitory, easily-changing, and the ever-lasting materials in his works. Much of his output, including his two-dimensional works, have a strong sense of sculptural materiality, and Prof. Kanai’s suggestion that s-cultura can also mean “outside of culture” may broaden our interpretation of these works.

Moreover, the creatures and food producers on the planet are the ones who sense the great flow of time, or cyclical time. Their experience and wisdom have accumulated even before the SDGs and COP, which we hear so much about in the media, existed. It is also true that there are many people who cannot shake their distrust of the developed countries leading this framework due to their fluctuating practices, often determined by large corporations and international conferences by G7. From the Global South, one might hear voices asking who has defined “culture” and who has been placed outside of it. It must have been significant that these voices were heard at this year’s documenta, the main battleground of art, which has been largely defined by the historical context of the West. What kind of change might we expect in this larger turn of time? Simultaneously, how does it relate to the role of art in securing a quiet time and place to step back from reality for a moment, to love a single bean or to be moved by a single note on the piano?

Prof. Kanai spent about two months with us talking about Arte Povera and its subsequent development, linking it to Hirose’s proposal for a “Common Farms” in Kinan. In the process, we were taught Boetti’s concept of “decentralization” and Penone’s concept of “outside culture.” We would like to use these topics as hints for our future practices. Thank you very much.

KANAI Tadashi, professor at Shinshu University

Born in Fukuoka Prefecture, Japan in 1968. After working as a curator at the Toyota Municipal Museum of Art (2000-2007), he has been Professor at the Faculty of Humanities, Shinshu University since 2007. His curatorial exhibitions include Arte Povera (Toyota Municipal Museum of Art, 2005), Vanishing Points (National Gallery of Modern Art, New Delhi, 2007), Aichi Triennale 2016 (co-curated by Aichi Prefectural Museum of Art, and etc., 2016). He has also authored Trans-Figurations: Sculpture and Photography in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction (AKAAKA Art Publishing, Inc., 2022), co-authored Exploration of the Imaginary 1 The Anatomy of Sculpture: From Donatello to Canova (Arina Shobo, 2010), and co-translated Art Since 1900 (Tokyo Shoseki Co., Ltd, 2019), etc.

SUMITOMO Fumihiko, curator/ professor at Graduate School of Global Arts, Tokyo University of the Arts. Director of Arts Maebashi from 2013 to 2021, where he curated Listening: Resonant Worlds (2020), The Ecology of Expression – Remaking Our Relations with the World (2019) and Foodscape: We Are What We Eat (2016). He curated Demarcation: Akira Takayama / Meiro Koizumi (Maison Hermès Le Forum, 2015), and co-curated Post Nature: Dear Nature (Ulsan Art Museum, 2022), Aichi Triennale 2013, Media City Seoul 2010. As a senior curator at Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo (MOT), he curated the exhibition Tadashi Kawamata: Walkway (2008). He is co-editor of From Postwar to Postmodern, Art in Japan 1945-1989: Primary Documents (Museum of Modern Art New York / Duke University Press, 2012) and a founding member of Arts Initiative Tokyo (AIT).

Editor/Translation: YABUMOTO, Yuto

Translation: YAMAMOTO, Reiko

Localization: STRUCK-MARCELL, Andrew