Orange Collective

Workshop Report – “Try it once, Try it again” and “Walking, Knowing and Interacting” at Kinan Art Week 2023 by Satoshi Hirose.

We seem to see the same things, but we each see them differently. Individual memories and experiences can act in different ways and we may perceive the same event as something different. It suddenly feels as if people are lonely and unable to understand each other, but this is not true, and that is why the world is as diverse as the number of people in it.

I am sorry to start off on a bit of a slow track, but this is the impression that came to my mind when I looked back on the video recording of Satoshi Hirose’s workshop at the Kinan Art Week 2023. The sunlight pouring into the former classroom of the old wooden primary school immediately brought back memories of a warm autumn day. There, the participants are working and conversing under Hirose’s facilitation. It is a scene where time passes slowly and peacefully. Watching it over and over again, you realise that what you see changes from the first time you see it to the second or third time you see it. In other words, not only other people, but even the same person can change the way they look at it. The purpose of this workshop is to notice changes and differences, not consistency of experience.

Furthermore, the participants of course have different motives for participation, different circumstances that led them to leave their jobs and families, and they sometimes reflect on themselves through their own actions and statements with an awareness of others in front of them. Seeing how each of the participants was working on a common task, while holding on to such detailed individuality.

The workshop proceeded in this way. First, participants are instructed to look at lightweight bricks commonly found at home improvement centres and to carve similarly sized Styrofoam blocks to create the same shape. They experience basic training in the creation of artworks, and in carving imitations. This is a seemingly simple act of reproducing a shape seen and captured by hand, but until the participants get used to the softness of the material and the handling of the tools, their hands do not listen to them as if they were other people. However, as they gradually become accustomed to handling the knife and sandpaper, they are driven by the desire to reproduce more detail. In the film, too, we can see in a short time the change from the initial bewilderment to the increased concentration.

Next, participants are asked to wrap the yarn around until the material inside is no longer visible. As they were already familiar with the surface texture by touching the two blocks, they wrapped the yarn around them in a regular or messy manner, depending on the person, pulling lightly to ensure that the yarn wrapped tightly along them.

Now, the workshop has come to this point in the production section, after which the table at which we were working was pulled aside and all the blocks were placed on the floor. The exterior is wrapped in yarn, so it is no longer possible to distinguish between bricks and Styrofoam. Participants were asked to think of one or the other, choose one and pick it up. If they do so, after a soft, fluffy touch, the muscles in their hands and arms become slightly unbalanced if the weight they feel is different from their brain’s prediction. The simple wager makes them very aware of the connection between the brain and the arm.

The second part of the workshop is a complete turnaround: visual perception is stopped by blindfolds. While unable to see anything, participants pick up an orange, peel it and eat it. They are also handed a leaf of a plant, which they lightly rub and smell. All of these experiences heighten the senses of touch and smell as a result of being deprived of sight. Citrus fruits, in particular, are characterised by their leaves, not their fruits. Surprisingly, one participant guessed that the leaves distributed among the many citrus fruits were lemon and kobumikan.

At the end of the workshop, the participants left the old wooden primary school and walked through an orange orchard with many trees bearing fruit in abundance, where the farmer taught them how to grow and identify the best tasting oranges. While standing in front of the oranges before they were harvested, the farmer explained how he manages the balance between sweetness and acidity produced by the nutrients absorbed from the soil. It was very interesting to learn that such unseen activities are reflected in the length and width ratio of each orange and the bumpy surface of the oranges. The farmers can certainly see things that we cannot.

Moreover, the children loved not only eating the tasty oranges, but also riding on the back of the light truck on the steep slopes. A routine that is commonplace for farmers was gaining popularity on a theme park ride level. Also, it was impressive that the farmers said at the end of the event that they usually just ship their crops every day, but that it was good to hear directly from the participants that their food tasted good.

In fact, it may not be easy for many primary producers to realise the value of what they produce. This is because there is an intermediary (the market) between them and the people who put it into their bodies as nourishment and enjoy it. Farmers control the taste and shape of their crops based on market demands. We, who ultimately receive the bounty of the crops, are called consumers. We, the consumers, rarely know what the farmers are doing and thinking about.

From his first visit to Kinan, Hirose went to see the farms and spoke to many farmers, and was fascinated by their work and knowledge on the plant. At the same time, he felt that their fascinating experience and knowledge went far beyond the production of oranges as a commodity. In the words of the farmers, there were stories that were connected to the history of the land and the wisdom for humans and other living creatures to coexist together. This is the very culture that is created through daily contact with nature. It is not something that can be talked about only by the act of putting products on the market.

Hirose then considered that “I understand that the production of products is important as a livelihood. However, I want to create a place where the rich knowledge and experience of oranges can be unleashed”. This proposal led to the idea of a ‘commons farm’. The background to this was probably the experience of visiting farmers in Italy, where he currently lives, with a rich food culture, including wine, is produced.

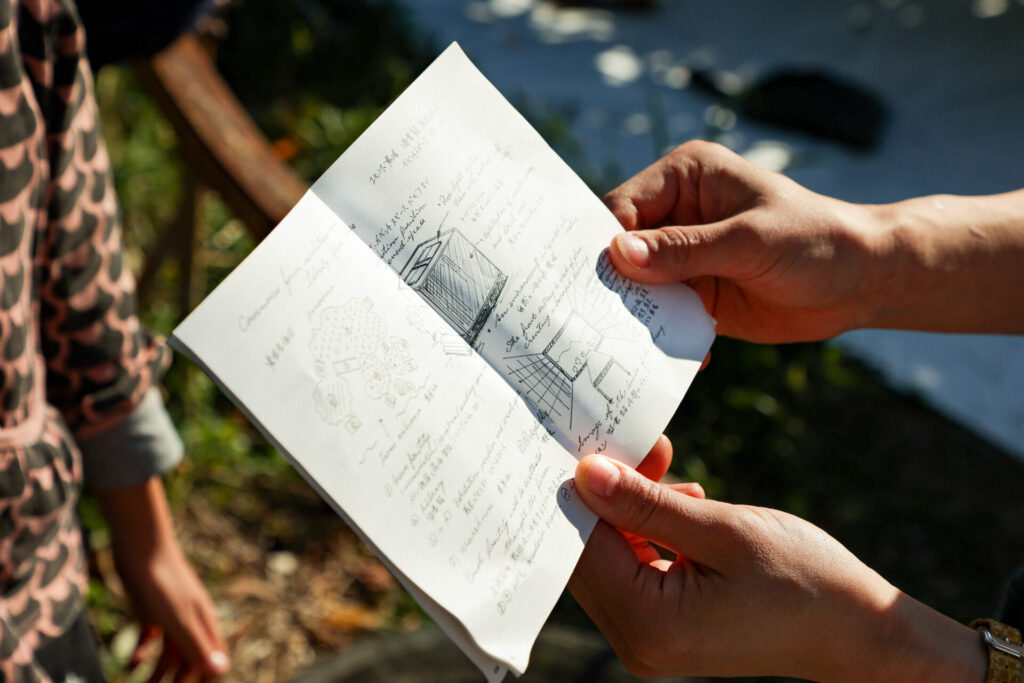

In the small pamphlet he produced this year, Art Project “Commons Farm”, he presents a mandala by Kumagusu Minakata, who explored the world of microorganisms in which all living things depend on each other, and envisages a place where people from different backgrounds can gather while growing crops in order to consider the possibility of overcoming the division of labour in industry and society. The idea is to create a place where people from different walks of life can come together while growing crops.

Is it a utopia? Is it an utopia or a place that exists nowhere else? The practice of making, reflection on one’s senses, feeling the rich bounty of plants, and gathering not only farmers but also various people from the local community to talk with each other actually took place on an October day in Kii-Tanabe, in a wooden former primary school and a farm. The warm autumn day was like a glimpse into the future of the Commons Farm.

Fumihiko Sumitomo (curator).

All photos by Manabu Shimoda (coamu creative)