The future is coloured by pine smoke ink -Current situation and challenges in the ink industry –

Guest

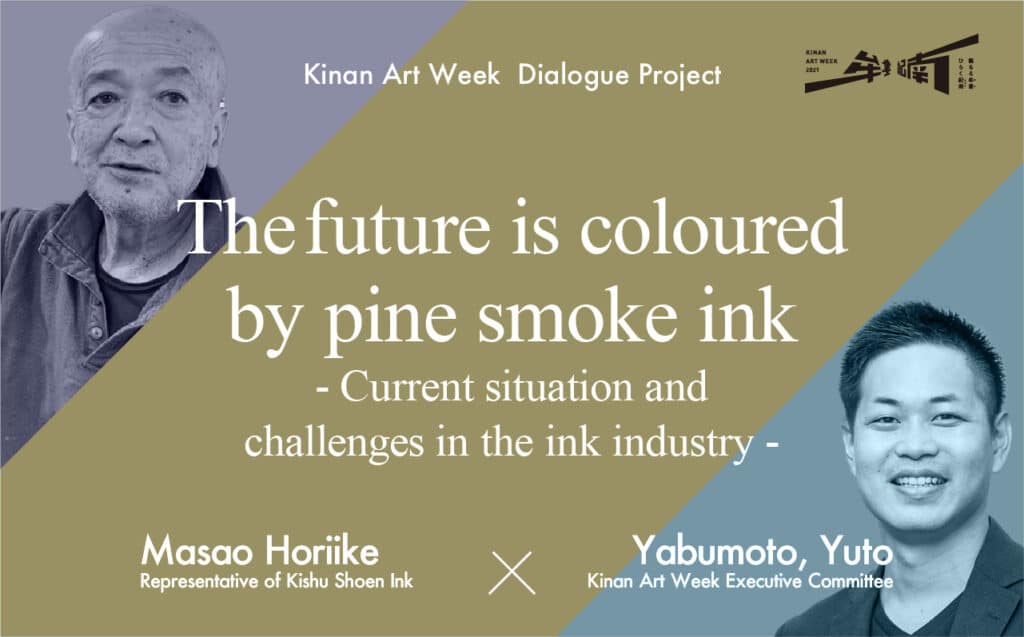

Representative of Kishu Shoen Ink Studio

Mr. Masao Horiike

Born in Shizuoka Prefecture. He is the only ink craftsman in Japan who makes “pine smoke,” which is the raw material for ink. At the age of 35, he moved to Kinan and started making pine smoke ink, which he later sold. He currently has a workshop in the Ayukawa/Oto area of Tanabe City, where he spends his days working alone with his ink. He also works as a sumi-e painter, producing his own works, which he sells in his online shop. He is concerned about the decline of the ink industry as well as Kishu Shoen, as he currently has no successor.

Ink Studio Kishu Shoen

Ink Studio Kishu Shoen Sumi Paintings by Masao Horiike

Interviewer

Yuto Yabumoto

Kinan Art Week Executive Committee Chair

<Editing >

Kinan Editor by TETAU

https://good.tetau.jp/

Table of Contents

1. History of ink介

2. The roots of the Kishu Shoen

3. The depth of the “Saienboku” (coloured smoke ink)

4. How to feel the art

5. How can we preserve the culture of ink?

6. The future of the ink industry

1. History of ink

Yabumoto:

Thank you very much for taking the time to talk to us. Today, we would like to ask Mr. Horiike about his practice as an ink craftsman and his thoughts on ink making.

I would like to ask you a few questions about the history of ink. When did people start to use ink?

Mr Horiike:

It is said that Sumi (Indian ink) was first introduced into the world about 2000 years ago, during the Han Dynasty. Later, around 600 A.D., during the reign of Prince Shotoku, the Japanese envoys to the Tang Dynasty brought ink to Japan. In the beginning, sumi ink was treated as an ultra-luxury product, but as time went on, it came to be used by the general public. Until the pre-war period, sumi ink was used as a writing instrument, and it is thanks to this that we have been able to preserve so many historical documents.

Yabumoto:

What are the materials used to make ink?

Mr Horiike:

Sumi ink is made up of soot*1 and glue*2. Soot is carbon, which is combined with glue to make a clay-like substance called sumi. Sumi can be used to write on anything that doesn’t repel water, and once it’s written, it doesn’t disappear easily. It is also very beautiful when mixed with different colours of sumi ink when drawing or writing. Moreover, the ink is very durable and can be used for 10 years.

In my workshop I make sumi using exactly the same method as 2000 years ago. However, since there is no one to succeed me, the future of this ink-making process may disappear.

*1 Black carbon particles emitted with the smoke when something burns.

What is soot (Kotobank)

*2 A substance consisting mainly of gelatine extracted from animal bones, skins and tendons.

What is glue (Kotobank)?

Yabumoto:

I once had a conversation with people involved in agriculture, forestry and fishing, and they all said that it was difficult to maintain their businesses. It is very likely that they will really disappear in the future and I think we must protect them.

Mr Horiike:

For around 1000 years, the mountain people of Kishu have been burning pine trees to produce “Pine smoke”*3, the raw material for ink. In our industry, we call the soot from pine trees “Shoen” and the ink made from it “Shoen-boku”. Before the war, pine smoke was known as “black diamond” and was very popular in Japan.

In the past, there were three big pine smoke wholesalers in Tanabe, and the wholesalers sold the pine smoke brought by the mountain people to ink shops all over Japan. In the old days, the mountain people of Kishu could make a living from this, but nowadays they can’t survive just by producing the raw materials. I am the only craftsman in Japan who makes pine smoke, but as I told you, there is no one to succeed me. I feel very sad that I cannot tell the history of sumi ink and the current situation of sumi ink making to the people who will be responsible for the future.

*3 Soot made by the incomplete combustion of resin-rich pine and other wood.

What is pine smoke (Kotobank)?

2. The roots of the Kishu Shoen

Yabumoto:

We would like to ask Mr. Horiike how he got started with Kishu Shoen. Are you originally from Kinan, Mr Horiike?

Mr Horiike:

I am from Shizuoka prefecture and I was an ordinary businessman until I was 35 years old. I moved to Tanabe 35 years ago with the motivation that I wanted to live in the countryside. Originally I built my workshop in the Mori area of Tanabe, but many shops in the area had closed down, so I decided to move to the Oto area in Ayukawa, Tanabe, in view of the situation.

Yabumoto:

Why did you choose your current location?

Mr Horiike:

When I was looking for a plot of land, I was introduced to it by a man from Oota. This place has very little humidity, which is perfect for ink, which is prone to decay. There is also a beautiful river near the workshop, where fireflies sometimes appear. I love Kinan because there are many places with rich nature.

Yabumoto:

Have you been working in this workshop since you came to Kinan at the age of 35?

Mr Horiike:

For about two or three years after I started Kishu Shoen, I worked as a soot maker making pine smoke. However, I thought that I would not be able to live like this, so I decided to make ink. I was able to make ink without knowing anything about the process, but at first it didn’t sell at all. . Later, through repeated trial and error, I discovered that I could make the best use of the pine smoke from Kishu to produce the ink, and here I am today.

In the past I have been given the job of making blue ink. When I actually delivered the ink, the client liked it very much. In fact, it was easier to sell than the black one because coloured ink was rare.

Also, one of the publishers told me that they were going to publish a book featuring sumi ink and fountain pens, and my products were featured in it. Once the book was sold, I started to sell a tremendous amount of sumi ink at once. I have also been invited to participate in the “Japanese Traditional Exhibition” held by Takashimaya from time to time*, and I have been promoting the appeal of Shoen Sumi at various places.

*Reference Sumi Ink Studio Kishu Shoen Masao Horiike Facebook “Nihonbashi Takashimaya ‘Japanese Tradition Exhibition'” (May 17, 2018)

Yabumoto:

The pine smoke is made from pine trees, does Mr. Horiike also cut down trees?

Mr Horiike:

I don’t have the skill to cut down the trees, so I buy the best quality pine trees with oil. It might be easier to understand how the ink is actually made if you see the workshop. I will explain it to you as we walk through the workshop.

The first thing to do is to split the pine wood in half and put it in the oil stove to burn; it takes about 5-10 minutes for one piece to burn, so you have to keep splitting the wood and putting it in the fire. Afterwards, I collect the pine smoke in the stove and remove the rubbish. Then I pour it into a mould together with glue dissolved in water and let it dry, and finally the ink is ready. Incidentally, 500kg of pine wood produces 10kg of pine smoke, and this process alone takes nearly 100 hours.

Yabumoto:

I think it’s really amazing that you’ve managed to keep up with the incredible amount of work alone.

This building is located near the workshop and is very beautiful, with moss spreading around it. What is the use of this place?

Mr Horiike:

When I’m making soot I can’t take my eyes off the work, so I used to use this place as a sleeping accommodation. Now I go to the workshop from my house in Tanabe. By the way, I built the workshop and this building together with the contractor.

Basically, I enjoy doing everything by myself, but it’s still a lot of work. If I can make more “valuable things”, maybe I can have a successor. If I want to leave the ink industry to the future, it is not enough for me to do it alone. I think it is important to think about the future of ink making from the point of view of many people, not only craftsmen like me.

3. The depth of the “Saienboku”(coloured smoke ink)

Yabumoto:

How do you make the “ink that’s other than black” that you mentioned earlier?

Mr Horiike:

Black ink is a mixture of soot, a black pigment*4, and glue. In the same way, if you mix red pigment with glue, you get red ink. After a lot of trial and error, I have commercialised the coloured ink as “saienboku”(coloured smoke ink). It is very beautiful in its own right, but if you mix the two together, you get a much deeper expression. Moreover, even if you pour water on the dry ink, it will not bleed at all. You can paint over the ink,, which is an advantage not found in paints or other materials. I also draw ink paintings myself and it’s very fun.

*4 A general term for coloured opaque powders which are insoluble in water, oil or alcohol, and which colour objects in their powdered dispersion.

What is a pigment (Kotobank)?

Yabumoto:

How long have you been painting?

Mr Horiike:

It’s only been about five or six years. But I have been practicing for a long time because I need to show the advantages of sumi ink to my customers in a way that is easy to understand. With sumi ink, you can draw very freely, and I think children will be able to express themselves in many different ways at the Kinan Art Week event*.

*Reference Kinan Art Week Instagram “Original God: Exhibition of works” (20 November 2021)

Source: Adventure World x Kinan AW collaboration project! Let’s draw an original god with ink painting! (Kinan Art Week)

Yabumoto:

The event will be attended by local children and we hope that it will encourage local people to take an interest in sumi and ink painting.

What do you think “good ink” means to you, Horiike?

Mr Horiike:

I think it is the beauty of the writing, the blotting and the colours. We used to draw with only two colours, black and brown, but now we have a wider variety of colours and a wider range of expression. I am sure that the children will make wonderful pictures even with only one black colour. But if you use different colours of ink, you can create more interesting expressions. There are still a lot of people who don’t know about sumi ink, so I hope Kinan Art Week will be a good opportunity for them to get interested in it.

4. How to feel the art

Yabumoto:

I myself don’t believe that art itself contributes to the economy, but I do believe that there is a great deal we can learn from contemporary artists. In that sense, through Kinan Art Week, I want to create opportunities for people to come into contact with their ideas and philosophies.

Also, some of the works of contemporary artists are worth over 10 million yen. In the same way as them, I think that the leaders of primary and secondary industries could sell a kilogram of sea bream for 1 million yen or a piece of mandarin orange for 1 million yen. In this sense, there may be people somewhere in the world who would buy a stick of ink for 1 million yen.

Mr Horiike:

If the value of sumi ink goes up, the craftsmen who make it can live. Once, at a special exhibition at Takashimaya called “Japanese Traditional Exhibition”, there was an umbrella shop from Fukui prefecture. The shop was selling umbrellas of various designs, and they were selling umbrellas that cost exactly one million yen each. The customer who bought the umbrella said, “I wouldn’t be proud of buying a million yen car, but I would be proud of a million yen umbrella”. As Mr. Yabumoto says, I think there are people who understand the value of our products.

Yabumoto:

It’s all about, “what do you value?” I think that is the most important question. Next year, we would like to hold an exhibition using mandarin oranges to discuss the question “Why do we eat oranges? For example, in Japanese mythology, in the myth of Izanagi-no-Mikoto and Izanami-no-Mikoto, there are tachibana trees* . For me, it is important to think: “Why do the tachibana trees appear?” In this sense, if we dig up the origin and the idea that human beings started to use ink, more people may be moved and inspired by it.

Mr Horiike:

I think it’s a real testament to the power of the artist. However, since they base their work on their own ideas and expression, there is the problem that if something doesn’t strike a chord, it won’t be seen.

We often meet calligraphers through our work. Some of them, as they practice imitating other calligraphers, believe that they have to imitate everything. On the other hand, there are also calligraphers who have made their mark in history, and I think that sometimes people who see their work feel that they tremble when they stand in front of it. I’ve never had that feeling, but I suppose if you are a sensitive person, seeing art can move you. In order to develop a sense of “being moved by art”, it is also necessary to have a knowledge of history and culture.

5. How can we preserve the culture of ink?

Yabumoto:

After all this time, I felt again that sumi ink is a writing instrument that excels in “leaving a mark”. I think there is no other tool that is so water-repellent and can express so much depth.

Mr Horiike:

What you write with a fountain pens or ballpoint pens disappears after about 100 years, while what you write in sumi ink remains for over 1000 years. Sumi ink has such a long history, but I think today’s children have less and less chance to touch it.

Yabumoto:

Why have they fallen out of use? Is it because we use too much of what is convenient?

Mr Horiike:

That may be part of it, but I think the main reason is that people don’t use the brush anymore. It is inevitable to use sumi ink when writing with a brush, but nowadays most people use ballpoint pens. Although the opportunities to learn calligraphy and ink painting have diminished, I am sure that learning about them will be useful in the future as part of Japanese culture.

Yabumoto:

I really like a calligrapher called Morita Shiryu*. In my opinion, Morita Shiryu depicts a world that “opens while closing, and closes while opening”. This worldview is exactly what Kinan Art Week is about.

I also believe that calligraphy expresses “a view of the world in which flamboyance is abolished and only the essence is sought”. I am sure that this way of thinking is necessary in our time, and in this sense, the era of sumi ink will come once again.

*Reference: Morita Shiryu (Toyooka City Virtual Museum)

Mr Horiike:

In the future, children should be more familiar with foreign countries. In this sense, I hope that in the future there will be more time to learn about Japanese history and culture. I am sure that people who are educated in this way will be respected. However, I think that Japanese people are too busy and have less and less time to learn, and I also think that more and more people disregard the history and culture that we have cherished for a long time. It’s a shame.

Yabumoto:

It is truly amazing that the mountains of Kishu have survived to this day, even under such circumstances. Looking back on our conversations with people involved in forestry and charcoal making, it was clear that the mountain people of Kishu were deeply concerned with the “relationship between mountains and human beings”. On the other hand, in the fishing industry, there were very few people who delved into the “relationship between the fishing grounds and human beings”. Perhaps if we don’t continue to think about ‘the way people are in relation to nature’, the industry itself will disappear.

Mr Horiike:

In terms of preserving industry, perhaps craftspeople need to do more than just “make things”. For example, if a fisherman opens a restaurant and serves the fish he catches, more and more customers will be attracted by the “fisherman’s cooking”.

However, it is very difficult to be a craftsman and a salesman at the same time. When we, sumi craftsmen, talk about sales, we tend to focus on “our passion for making sumi”. However, our customers are more likely to ask “What is this ink useful for? or “What is the difference between this ink and other ink?In other words, if you can’t explain why the customer wants to buy your product, you won’t sell it at all. I feel that if we sell with this in mind, we will eventually be able to preserve the industry itself for the future.

6. The future of the ink industry

Yabumoto:

At present, Mr. Horiike is the only ink maker in Japan who makes pine smoke, and I believe you are the “last bastion”.Are you taking on any apprentices?

Mr Horiike:

It is difficult to make a living in this industry, so it is difficult to get apprentices. No matter how good the ink we make, if people don’t buy it, we don’t get money. Some of my inks cost over 10,000 yen. We have to ask ourselves “How can we get people to buy these products? Until now, it has been the job of wholesalers and retailers to deliver the products made by craftsmen to customers. But we don’t know what will happen in the future, so we are very worried.

Yabumoto:

In this sense, I think the most important thing in making sumi ink is to find the value of the ink. What do you think is the value of the ink you make?

Mr Horiike:

As I make my products in Kinan, the most important value of my products is that I use pine smoke. I also make coloured smoke ink, so I think that if painters can use it, they will be able to express themselves more widely. Many people don’t change the tools they are used to using, but I think it is more fun to use a variety of tools to paint with. I also think that if calligraphers and children enjoy using ink, they will be able to create interesting works. In this sense, I think it is better for people who use sumi ink to communicate its appeal, rather than for ink craftsmen like myself to promote their products.

Yabumoto:

What do you think the ink industry or Kishu Shoen will look like in 10, 30 or 50 years’ time?

Mr Horiike:

To be honest, Kishu Shoen may end in my generation. However, as a lifelong active worker, I will continue to do my best. In order to protect the ink industry, our first priority should not be to “sell ink” but to “convey the goodness of ink”, and I would like to keep this idea in the future.

After all, sumi ink is a writing instrument that has been handed down through the history of Japan, so no matter how you look at it, it’s a good thing. If it were not, it would have been eliminated long ago. Of all the things that have come from the West, such as paints, there is nothing that can compare to the quality of sumi ink. In this sense, I believe that we should pass on to the future not only the ink itself but also the culture of ink making.

Yabumoto:

First of all, we would like to create an opportunity for local people to learn more about sumi ink through the events we hold during Kinan Art Week. We would be happy to help in any way we can to preserve the achievements of the ink industry and Kishu Shoen for the future.

It was a great learning experience. Thank you very much for your time today.

Mr Horiike:

Thank you very much.