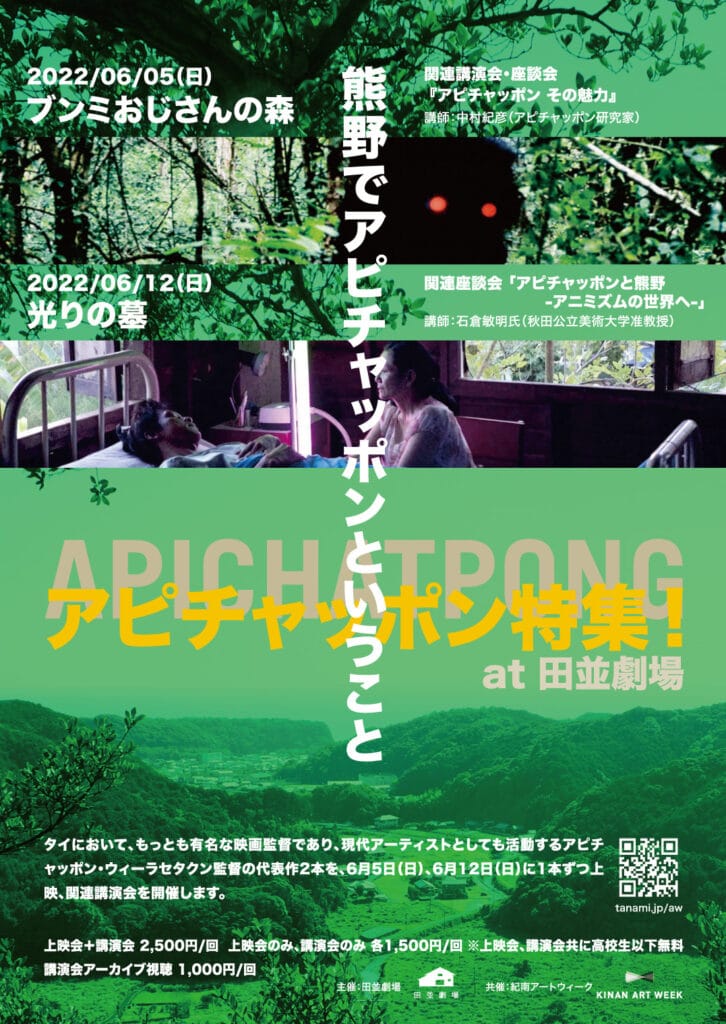

Kumano and Zomia: thorough Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s Artistic Expression

12th May 2022

Kinan Art Week Yabumoto Yuto

1 Introduction – Is Apichatpong a Contemporary Shaman?

I am from a town called Khon Kaen in the north-east of Thailand, so I have always felt like I am a ‘minority’ in Thailand. This has not changed in modern times. In Thailand, governance and power are all concentrated in Bangkok, and because I am gay, I have always felt that I am a ‘marginal person’ in relation to the center. –

–Apichatpong Weerasethakul, ‘Apichatpong on All Feature Films’

I first met Apichatpong Weerasethakul (born in 1970) in an Indian restaurant in Chiang Mai, Thailand. Despite being one of Asia’s leading film directors, having won four awards at the Cannes Film Festival, I was surprised by his friendliness and the spontaneous atmosphere he exudes. The friendliness that Apichatpong has cannot be unrelated to the lush mountains, rivers and other natural features of Isan, the northeast region of Thailand where he was born and raised.

However, Apichatpong’s language suddenly starts to heat up when it comes to political talk about Thailand and neighbouring countries. This also seems to stem from Isan’s complex history. During the process of modernisation and centralisation of Thailand, phi (belief in spirits) has been marginalised by the nationalisation of Buddhism, and small Isan histories and stories have been altered and erased.

When coming into contact with Apichatpong’s work, I am intuitively reminded of my hometown, Kumano, located in the southern part of Kii Peninsula, Japan. The philosopher Takeshi Umehara (1925-2019) described Kumano, along with the Ainu, the indigenous people of Hokkaido in the Northern part of Japan, and the Ryukyu, another indigenous people mainly from Okinawa, as the original cultures of Japan, which retains strong traces of practices and beliefs from the Jomon period (c. 14,000–300 BCE). However, in what elements are Kumano’s culture rooted? Kumano’s diverse beliefs and myths are undoubtedly related to its special geographical conditions, which are said to be ‘near the mountains and the sea’, and to its natural environment, including forests, trees, superimposed mountains, the coast onto which the Kuroshio Current flows, and rivers that connect the mountains and the sea.

Apichatpong, who evokes this intuition in us, may be a contemporary shaman. In his expressions, the films evokes the imagination of previous and next lives, and clarifies the ontology of the soul. It also brings to light invisible spirits, ghosts, and memories of the land. I think that Apichatpong’s worldview seems to have something connected to Kumano’s shamanism, which governs ‘death and rebirth’.

2 Kumano and Zomia

The word ‘Zomia’ may be the link between Kumano and Isan. ‘Zomia’ is derived from the Tibetan and Myanmarese word ‘Zomi’ meaning “highlander”, and refers to the mountainous areas of continental South East Asia (Vietnam, Cambodia, Laos, Thailand and Myanmar) and southern China. The Isan region where Apichatpong grew up is also included in the scope of ‘Zomia’, and the Karen people in ‘Mysterious Object at Noon’ (2000) and ‘Blissfully Yours’ (2002) are the exact type of people who live in the Zomia world. The people living in Zomia have lived in an egalitarian society, away from any kind of domination by the state, such as taxation, military service, slavery, etc, while believing in animism, dispersing, and moving repeatedly. In the past, anthropologist Keiji Iwata (1922-2013) investigated the lives of mountain peoples in South East Asia and stated that animism, oral culture, movement and behaviour in small groups, as well as slash-and-burn agriculture in the evergreen-leaved forest zone, have much in common with the beliefs of the ancient Japanese . According to interviews which were conducted with charcoal burners in the mountainous areas of Kumano, people with Zomian characteristics, such as animist beliefs, migration, and oral culture, are also present in Kumano.

Anthropologist James C. Scott states that Zomia can be seen as a place of ‘Yin’, which means that it is a ‘negative’ or “dark” region. On the other hand, speaking of ‘Yin’ regions, in the Kojiki(Records on Ancient Matters)and the Nihonshoki (the Chronicles of Japan), Kumano is referred to as ‘Nenokatasu-kuni’, and folklorist Gorai Shigeru (1908-1993) describes it as “a place where the spirits of the dead gather”. Both Zomia and Kumano are ‘Yin’ regions, and are almost like places of foreign origin. The mythologist Taryo Obayashi (1929-2001) also states that Japanese mythology is influenced to a significant extent by the stories of South East Asian mountain peoples, and that Kumano and Zomia are linked at the mythological level as well.

In addition, Zomia has an expanse that includes not only mountains and forests, but also oceans and rivers. There is a theory that some people continued to move as sea gypsies via ‘Zomia on water’ through oceans and rivers, in order to break away from the monoculture flatland world. According to Kumano historian Koichiro Suginaka, South East Asian wooden boats, hollowed out of a single large tree, sometimes drifted into the Kumano region, floating on the Kuroshio Current, and there is a possibility that the water bound Zomi discovered Kumano, an attractive asylum (refuge) in the ‘mountains and sea near-by’, and returned from the sea to the mountains and forests again.

3 Zomia and Kumano-like Expressions

As noted above, Zomia and Kumano may share the same ideological roots, and these similarities/differences are examined below from the perspective of Apichatpong’s artistic expression and Kumano’s cultural expression.

(1) Zomian expressions of animistic thought

As many experts have pointed out, Apichatpong’s expression is characterised by Zomia, or animistic-like expression. For example, the ‘memory of things’ is often depicted in Apichatpong’s works. In the short film ‘Emerald (Morakot)’ (2007), a floating feather-like object in a closed hotel describes past memories, while in his latest feature film ‘Memoria’ (2021), a man named Hernan, who can read the past memories of objects, appears and reads the ‘memories’ recorded on stones and trees.

Animism is said to be a primitive religion that permeated every corner of everyday life before the establishment of religion and mythology. Anthropologist Keiji Iwata states that “Animism is generally translated as ‘spirit belief’ and means the belief of people that not only humans but also all animals, plants and inanimate objects have their own soul (spirit, anima).” In Kumano, many animistic elements exist, as exemplified by the Nachi waterfall, where the kami (gods) of Kumano coexist in a great variety of rocks, stones, trees, forests, islands, waterfalls, pools, wells and caves. Folklorist Kanichi Nomoto states ‘Treating natural objects as the existence of kami (gods) can be found throughout Japan, but Kumano has a greater number and variety, in quality and distribution, of kami to the extent they can be described as characteristic of Kumano’.

-When I look at the ‘forest’, the hills and valleys, my previous life as an animal and other things appear…

This is the first section of the all-too-famous film ‘Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives’ (2010). Boonmee, who has a diseased kidney and little time left to live, summons his wife’s sister Jen and nephew Tong to his plantation in Isan. There, his wife Huay, who died 19 years ago, visits him as a ghost, worried about her husband’s illness, and his son Boonsong, who disappeared several years ago, also comes as a monkey spirit to welcome Boonmee. Boonmee sits around the table with his wife’s ghost, the monkey spirit and other ‘diverse transcendental beings’ and faces death in the mother’s womb-like ‘forest.” In ‘Blissfully Yours’ and ‘Tropical Malady’ (2004), the ‘forest’ is shown to be a place symbolising ‘life (sex)/death’ and ‘spirituality’ and occupies an important element in Apichatpong’s films.

On the other hand, Kumano’s “Forest” was described by historian Munematsu Yamada, “Kumano was a fundamental dark world for the inhabitants of this archipelago. To go through this dark death land was at the same time to return to the primordial womb from which we all came.” As stated in the article, ‘Death, sex and spirit traditions are deeply intertwined’, Kumano is a place where ‘life (sex)/death’ and ‘spirit’ are densely concentrated. Another characteristic of Kumano is that many of the shrines are dedicated to deities of the forest. For example, the Yagura Shrine in Tanami is a shrine without the typical architecture of a shrine, but centered around a large tree as its diety, and with the forest being the place where its god stays. Furthermore, the main deity of Kumano Hongu Taisha (one of the Kumano region’s three famous shrines) ‘Ketumiko-no-kami’, is said to be the ‘Ki-no-Mikogami’ a familial diety in a parent-child relationship with the shrine. It is also a tree deity who is identified as equivalent to Susanoo. This Zomia-like representation of the ‘forest’ as a symbol is commonly found in Apichatpon and Kumano.

(2) Zomia-like anarchist thought

As James Scott states in ‘The Art of Not Being Governed: An Anarchist History of Upland Southeast Asia’, the ‘state’ is a major obstacle in the history of the Zomian world. First, Apichatpong’s work reveals an anarchist ideology that is not bound by the existing state. In ‘Uncle Boonmee Who Can Recall His Past Lives’ and ‘Blissfully Yours’, he shows his affection for those on the periphery of the state, focusing on minorities in the countries surrounding Thailand, such as Laos and Myanmarese migrant workers.

The ‘supple resistance’ to the centralised state may be a characteristic of Apichatpong’s expressive practice. A striking example of this is ‘The Primitive Project’ (2009-), set in the village of Nabua, Isan. In the short film ‘Phantoms of Nabua’ (2009) in ‘The Primitive Project’, a group of boys are playing football on a grassy field at night in the village of Nabua, Isan. A blazing mass of ball-shaped flames (the ‘Phantoms of Nabua’, representing the soul) burns down to a white cloth in the screen, which eventually itself burns down.

A US airbase was established in Nabua village in the late 1960s, when the US invasion of Vietnam was in full swing, to bomb Indochina. In the 1970s, anti-government students established a base on the Thai-Laos border, and as a corresponding measure, the Thai National Army established a base in Isan. Civilians fled into the forest to escape the violence. Some of those people were labelled communists and have been involved in gun-fights. Although not explicitly stated, the ‘fire’ projected on the screen illuminates the memory of firearms and massacres, and seems to indicate resistance to the violent nature of the state.

In addition, ‘The Light of Longing’ (2021) which is an extension of the primitive project, is a reversed composition photographic work of the Mekong River on the Thai-Laos border. In reversing the composition, the work implicitly emphasises the memory of an erased place, while tracing the violence of state boundary determination and development against nature.

On the other hand, the novelist Kenji Nakagami (1946-1992), a native of the Kumano region, practised ‘supple resistance’ through his Kumano-based expressions as well. Socialist activity in the Kumano region became pronounced from the early 1900s. Activists such as Mouri Saian, the chief priest of Kozanji temple in Tanabe City, and other local socialists, such as Dr. Oishi Seinosuke and Naruishi Heishiro introduced early socialistic ideas through a newspaper called Muro Shimpo. Dr. Oishi was particularly interested in anarchist ideas, as he translated Kropotkin’s ‘The Conquest of Bread’. Against this backdrop, the High Treason Incident occurred in 1910 to assassinate the Emperor Meiji. So, Dr. Oishi, Koutoku Shusui, a Japanese journalist who was framed as the leader of the plot, along with a number of other socialists and anarchists from around the nation were all charged. While there was no sufficient evidence, and the government nevertheless sentenced 24 people to death, 6 of whom were from Kumano. The incident ended up being used as a political campaign by the government and gave a clear warning to all socialist and anarchists. The full story of these events were not revealed until after the World War II.

Kenji Nakagami, a Japanese post-war writer who publicly identify himself as a Burakumin, an unofficial type of low-caste person. He described the marginalised areas where he was born and raised as ‘alleys’. In Nakagami’s only reportage, ‘Kishu: Tales from the Land of Trees and Land of Roots’, he recalls the erased speeches of anarchists in the vanishing ‘alley’ of Kumano in his imagination. Also, the Akutagawa Prize-winning ‘Cape’ (1976), which shows the suffering and brilliance of people living on the periphery of the ‘alleys’, the trilogy ‘Karekinada’ (1977), and ‘The End of the Earth: The Supreme Time’ Chino-hate Shijono-toki (1983) are known as the Kishu-Kumano saga and created a distinctive world view. The trilogy expresses the protagonist’s conflict and resistance to his own father. His father, who claimed to be a descendant of a late 16th century military leader named Magoichi Saika, and built him monument. For Kenji, while erecting monuments is a typical act of the state, the real father in the same work is precisely a champion-like figure who develops and erases the ‘alley’, which symbolised the malevolent actions of the state. Although less well known, like Apichatpong, Kenji Nakagami also left behind film works shot with a 16 mm camera. The films recorded everyday scenes of people on the periphery living in secluded ‘alleys’ and seem to show a quiet resistance to the violence and hegemony of the state.

(3) Zomia-like oral culture

Finally, a characteristic of both Apichatpong and Kumano culture is the collective non-verbal practice by unknown people. As Toshiaki Ishikura, an art anthropologist, describes in ‘Narratives of a Catabolised Zomia: On Apichatpong Weerasethakul’s ‘Mysterious Object at Noon’, the people of the Zomia world have abandoned the written and literate world, and they may have resisted the state strategically through their unwritten ‘narratives’.

Along these lines, Apichatpong films often do not use actors as so-called professionals of the cinema industry. Similarly to the aforementioned Kenji Nakagami film, ‘Mysterious Object at Noon’ (2000), the story is spun by regular people in Isan and ethnic minorities through interviews crediting as “the ‘script: villagers in Thailand” instead of listing, for example, the director and screenwriter in order to eliminate the authority of job titles.

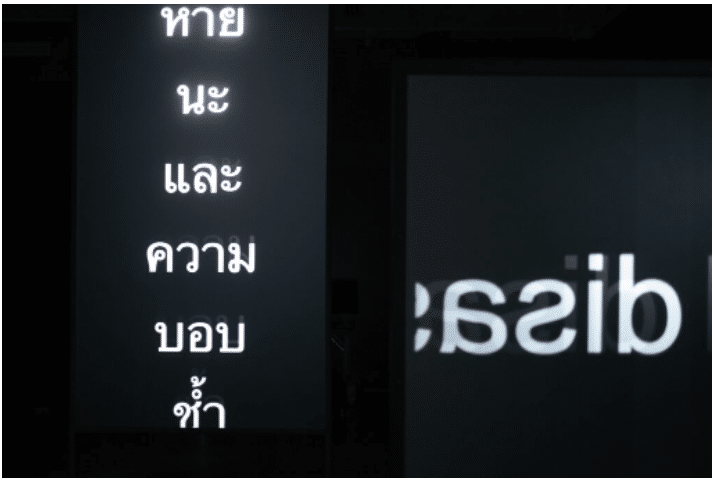

‘Minor History’ (2021), a video work linked to the aforementioned primitive project, is a series of works created by Apichatpong during the Covid-19 pandemic during his travels from Khon Kaen, Isan to Ubon Ratchathani, and includes his interviews with Isan people. In this work, the story unfolds from the starting point of the ‘death of a Naga (the God of snakes)’ and a ‘dead body in the Mekong River’, and towards the end of the story, where a series of huge inverted letters are continuously projected, showing the ‘violence of the text’ through visual representation.

On the other hand, Kumano faith practices are the result of the coming together of several unknown people. The unique festivals and traditional expressions of the Kumano region are such that indigenous people and outsiders have come together without any boundaries, and their wisdom has been integrated. They are not created or constructed on a paper, but are organically formed while practicing festivals, dances and performances through untranslated ‘narratives’.

Such festivals can be found throughout Japan. However, the length of Kumano’s history and the density of people who engage in the practices are distinct from others. In fact, at the fire festival held at another main Kumono shrine, Nachi-Taisha, torches are lit ‘on fire’. The red-hot torches, lit in front of Nachi Falls, repeatedly run around the 12 fan palanquins together with a large, dense crowd of people. This is said to be a reproduction of the battle between the indigenous people of Kumano and the Jinmu(Emperor Jinmu)army. The Otou Matsuri (another fire festival) at Kamikura Shrine which lies within the site of the last main shrine of the Kumano, has lasted for at least 1,400 years. Men dressed in white gather in great numbers on Gotobiki Rock in the darkness of the night and race down Mount Kamikura with torches in their hands, which have obtained their flame from a large torch deployed in the shade of the rock, to create a blazing fire dragon. It is said that if the Gotobiki Rock is seen as phallic, the men dressed in white are like sperm, while the fire symbolises women. The communion of red and white by this collective is truly indicative of the cycle of life. These Kumano non-verbal festive practices may be truly similar to Zomia-like oral culture.

4 Conclusion – Apichatpong’s Spaceships

As discussed above, Kumano can be thought of as such a part of the Zomia world that the two worlds can seem to be deeply connected underneath . Apichatpong, who illuminates this connection, is also a contemporary shaman.

However, what I find most interesting is that Apichatpong is not vocal in his resistance to the violent nature of the state. Rather, in ‘The Primitive Project’, Apichatpong illuminates the small memory of his Nabua village, but does not directly criticise it, rather playing with the young people of Nabua village, discussing the future with them and creating ‘spaceships’ together. This idea has been taken over by young artists from the Zomia world.

For example, in ‘Siamese Futurism’ (2021), Thai filmmaker Montika Kham-on (b. 1999) and her colleagues use the remaining water bottles in rural Thailand as spaceships to pose the question: ‘If there had been no centralisation of power in Bangkok, what kind of future would there have been for Isan?’ Starting with the story of Montika’s mother, who is from Isan, Montika falls asleep (she describes ‘sleeping’ as boarding a spaceship). The story of the past or the future is open to interpretation, but it is a story of a physical expression thatcould be described as a traditional or contemporary dance of a glowing Isan alien , and functions to make the passengers (the viewers) of the spaceship think about the past and future of the Isan people.

When I saw this work, I even thought that Apichatpong might have possessed Montika to show us the future. To add a word to my hypothesis at the beginning of this article, one might ask, ‘Could Apichatpong be a future-oriented contemporary shaman?’ In light of the work of Apichatpong and the artists associated with him, one cannot help feeling a strong need to nurture shamans/artists like Apichatpong coming from the Zomia world, and places like Kumano.