Orange Collective

The Myth of the Orange

–The Relationship Between the Kii Peninsula and Tachibana–

15th May 2022

Kinan Art Week Yabumoto Yuto

1 Introduction- Kii Peninsula, the Land of Bright Darkness

-I still have the perception that the Kii Peninsula itself is ‘in a shining bright darkness’.

This is a dark country. Behind the country of Japan, the Kii Peninsula is an unnamed dark country.[1] –

–Kenji Nakagami, Kishu: Tales from the Land of Trees and land of Roots.

‘Kishu: Tales from the Land of Trees and Land of Roots’ is the only reportage by the great artist Kenji Nakagami (1964-1992) from Kinan/Kumano. The ‘Land of Roots’ (nenokuni), the Kinan and Kumano region, is said to be a chaotic otherworldly world of ‘trees’ and ‘roots’ ruled by Susanoo, a place that continued to host the discriminated and exiled losers. [2]

Why did Kenji Nakagami use the phrase ‘bright enough to shine’ despite being in such a foreign land? In considering this, citrus fruits such as oranges and tachibana (橘, a kind of citrus fruit native to Japan) may provide a clue.

2 Plants and Myths- Citrus and the Sun

What is myth? In ‘Myth and Reality’, the Romanian religious scholar Mircea Eliade (1907-1986) states that ‘myths tell the story of sacred history’ and are ‘always an account of creation’, telling ‘how some things were made and came into existence[3]’.

Among these myths, there are many myths related to plants and citrus fruits in the world. They include cedar, zelkova, apple, cherry, peach, lotus, banana and so on. This is probably because people and nature alike have the desire to preserve and reproduce each species[4]. Plants appropriate to the local climate of each region are then utilized in mythology as symbols and media to promote people’s understanding. Examples include the ‘banana myth’ in the South Seas, such as Indonesia and New Guinea, and the ‘Konohana myth’'(flower-blossom myth) of Ninigi-no-mikoto and Konohanasakuya-hime (Flower-blossom princess) in the Himuka myth. In these, different plants, such as ‘bananas’ and ‘beautiful flowers’, are used as subjects based on differences in climate, but both offer similar explanations for the origin of human death.[5] [6]

In terms of citrus, the orange tree has the unique characteristic of producing white flowers on its branches and, at the same time, golden fruit. This characteristic has been utilized as a symbol of Christian mythology. In other words, the white flowers give the meaning of ‘purity’ and the golden fruit ‘fertility’, and have also been depicted in Western court painting as a symbol of the Virgin Mary, which has the meaning of both virgin and mother, as Cima da Conegliano and Gaudenzio Ferrari’s‘Madonna of the Orange Tree’ (1945) shows [7] [8] . Furthermore, in the Greek myth of ‘Atherante’s love[9]’ and in the pictorial representations of great western painters such as Botticelli’s ‘Primavera’ (1478)and ‘The Birth of Venus’ (1480)[10] and Cezanne’s ‘Still-Life with Apples and Oranges’ (1899), citrus fruits have been represented as a symbol of nature and fertility. Above all, citrus has been considered a symbol of the sun because of its round shape and its colour. [11]

So, have citrus fruits been similarly regarded as a symbol of fertility and the sun in Japan? We would like to try to speculate on the relationship between the sun and tachibana in Japanese mythology[12].

3 Japanese Mythology and Tachibana

(1) Chronicle mythology – Susanoo, the southern plant god, and Amaterasu, the northern sun god

[13]The Kojiki (Record of Ancient Matters) and Nihonshoki (Chronicles of Japan, hereinafter referred to as ‘Chronicle mythology’) are said to consist of a multilayered and pluralistic collection of myths from various systems, including (1) myths from southern China to Southeast Asia (southern systems) and (2) myths from the Korean peninsula and inland Asia (northern systems)[14]. The myth of Ama no Iwato in the Chronicles mythology describes an opposition between Amaterasu (the goddess of life, order, and the sun) and Susanoo (the god of death, destruction, the sea, and roots).

Of these, Susanoo has similar characteristics to his rowdy youngest brother ‘Rahu’ in Southeast Asian myths of the origin of eclipses and lunar eclipses[15] . In Southeast Asia, there are also many beliefs that gods and spirits dwell in trees[16], and Susanoo, the indigenous deity of Kinan/Kumano, is also a southern plant deity[17]. Furthermore, it is said that Susanoo’s violent rampage in Takamagahara, breaking up Amaterasu’s fields and scattering dung, may have been a form of agriculture (slash-and-burn farming) in his own way[18]. The body of Ogetsu-hime, who was slain by Susanoo, yielded millet, soya beans, and other cereals, and many other cultivated slash-and-burn crops. Many cultivated slash-and-burn crops were produced from her body. Thus, Susanoo strongly reflects the character of southern and Jomon-style agriculture [19].

On the other hand, Amaterasu, is the sun goddess who brings order and light to the world[20]. The myth of the descent of the Amaterasu line (the story of the descent of the emperor’s ancestors from the high heavens) is said to have entered from the Korean Peninsula as part of the ruler’s culture during the Kofun period, from northern China[21] under the influence of the great upheavals in Eurasia[22]. During the upheavals, in the ‘regime change’ of Japan, it has been politically used as a founding myth to introduce[23] new ideas. In this sense, the sun has been a powerful tool[24] for external rulers to establish their kingship and to construct a unifying ideology without being tied to a particular land or family lineage. In accordance with Mircea Eliade’s definition of mythology above, the myth of the descent of the sun and its successor, the myth of the Jimmu expedition, is a ‘sacred’ state story which is handed down within a central ruling group.

(2) Tajimamori, Ootachibana-hime and Izanami’s exorcism – myths surrounding the tachibana

In such a context, how does ‘tachibana’(橘), the original citrus fruit in Japan, function? Does the word ‘tachiban’, which appears frequently in Chronicles mythology, have any connection with citrus as a symbol of the sun or order?

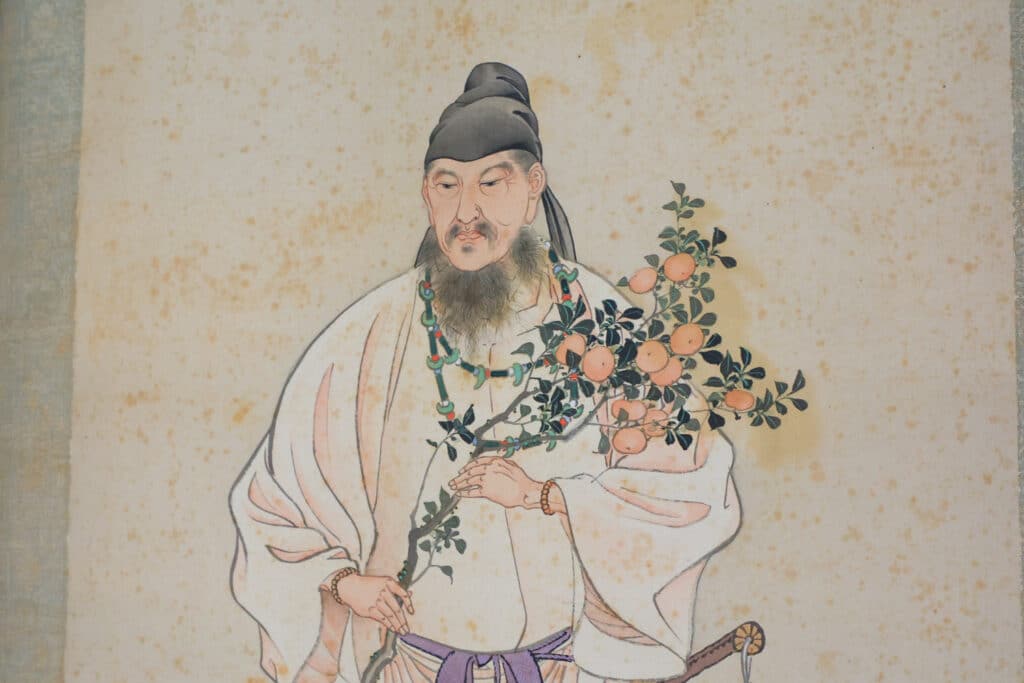

Firstly, related to tachibana is the well-known myth of Tajimamori[25] [26], who brought back tachibana from the Land of the Everlasting for the Emperor Suinin, who was lying on a sick bed. Tajimamori is enshrined as the main deity at Kitsumoto (橘本) Shrine in Kinan, Wakayama Prefecture27. The Tachibana (橘), here known as ‘tokijiku-no-kakuno-ki-no-mi’ (非時香果), whose golden round fruit was said to possess the power of immortality. ‘Tokijiku’ (非時, non-timeless) here refers to being independent of time, while ‘kaku’ (香, fragrant) is used to mean “fragrant” or “shining”.28 The luminous tachibana was thought to bring long life and good fortune[27] like the sun, which emerges from the everlasting world and goes in cycles through eternity. In modern times, tachibana would have attracted people like shining gold or money.

‘Tachibana’ also appears in the name of ‘Ototachibana-hime’, wife of Yamatotakeru, who plays a major role in the middle stages of the Chronicles mythology. Ototachibana-hime sacrifices herself as a substitute for Yamatotakeru at the Hashirimizu-no-umi (present day the Uraga Channel), and as a result, plays a role in calming the storm and advancing Yamatotakeru’s eastern expedition[28]. Yamatotakeru makes a tachibana tree, named after his name, the grave marker of his wife at Tamaura (present-day Kujukuri-hama Beach)[29]. This seems to make use of the belief in human sacrifice, in which the miko (shrine maiden) controls the raging seas, and also the miko representing the tachibana seems to produce the effect of relatively controlling and diminishing the raging power like Susanoo, while assuming the function of symbolizing Amaterasu-like goddess belief and regenerative power.

Finally, we return to the scene where Izanagi, pursued by Izanami and returning to the boundary between Yomi-no-Kuni (the underworld) and the sea[30] , performs ‘misogi’ (the act of bathing to remove impurities). The place where Izanagi creates Amaterasu from his left eye is said to be ‘Ahagihara of Odo, Tachibana of Himuka, in Tsukushi’, and the word ‘tachibana’ also appears in this purification exorcism.

First, ‘Himuka’ here is said to refer to a specific place in present-day Miyazaki Prefecture, but it could also be a generic term for ‘the land of the direct rays of the morning sun’, in other words, ‘a place where sunlight shines’[31]. ‘Himuka’ is the very place of the sun symbolized by Amaterasu, and it would not be out of place if there was a ‘tachibana tree’ there, which is thought to symbolize the sun.

In addition to the meaning of ‘tachi’ in ‘tachibana’ as in “standing straight and upright” and “conspicuous manifestation of the action of nature”, the word ‘tachi’ may also have the double meaning of “cutting off” as in “separating that which is connected”. The ‘tachibana’ may have existed as a ‘sacred tree’ that stood resolutely upright on the earth between the heavenly plateau and the underworld. I continue to have the image of Amaterasu’s presence being extremely emphasized in the scenes in which the three noble deities appear, coupled with the presence of the tachibana.

Incidentally, even today, its citrus fruits fulfil a kind of amuletic function (separating destruction and misfortune), such as being displayed on top of Kagamimochi (a traditional mirror-shaped offering made from rice cakes) at New Year, or placed at the entrance of the houses. In other words, citrus is a symbolic plant with an Amaterasu-like ideology of maintaining ‘order’ (positive) and separating ‘chaos’ (negative).

4 Finally – From the Perspective of the Dark State

Let us return to the first question. Why did Kenji Nakagami describe the Kii Peninsula as a ‘shining dark nation’? I cannot help feeling a kind of irony and pride for the Kii Peninsula in these words from Kenji Nakagami.

As mentioned above, when the myth of Oranges is unraveled, the logic behind it reveals the ruling logic of Amaterasu and her descendants, the emperors. In other words, the composition is that the positive principle of absolute light and order overthrows and dominates the negative principle of darkness and chaos[32]. And the symbol of this composition is the ‘tachibana’.

The Kii Peninsula is the largest citrus-producing area in Japan, despite its origins in the ‘land of roots’ ruled by Susanoo[33] . That is, the sight of citrus, the incarnation of the sun, being produced in large quantities (in particular, the production increased rapidly from the1960s to the end of the 1970s when Kenji Nakagami lived.[34]) in the ‘land of roots’ ruled by the ruler is just like a brand of the sun. Kenji Nakagami may have used the expression ‘shiningly bright dark nation’ as an ironic reference to such a situation.

On another point, Kenji Nakagami may be ironically referring to those who are continually misled by ‘brilliance’ and ‘brightness’. The word ‘capitalism’ is derived from the word ‘caput’. ‘Caput’ means “tip” or “head”[35], and in plants it means the tip of the pistil, namely the “fruit”. I think he wanted to explain the importance of the ‘dark state (the world of trees/roots)’ to modern society, which only aims at the proliferation of fruits and, by extension, money. Kenji Nakagami’s words are piercing in a time when it is becoming increasingly important to think about the trees and roots themselves, rather than aiming for the tip or the fruit.

Finally, in this age of ‘(fruit-based) capitalism’, Kenji Nakagami may have wanted to show that ‘positive/negative’, ‘Amaterasu/Susanoo’ and ‘fruit/root (tree)’ are inseparably linked, and that negative concepts such as root and darkness are important. This may be why the Kii Peninsula was used as a paradoxical expression of a ‘bright dark nation’.

In this regard, the American historian James C. Scott uses the term ‘dark twins’ to describe this inseparability of positive and negative. In other words, he argues that ‘nation/non-nation peoples’, ‘farmers/hunter-gatherers’ and ‘civilized people/barbarians’ are twins, both in sign and in reality. It is a historical fact that when nations and civilized people disappear, non-nations and barbarians also disappear (and vice versa)[36]. And, using the term ‘barbarians’ ironically, Scott notes the shocking fact that ‘barbarians’ have enjoyed the longest, most free, and a more equal golden age in the world[37] than those of us living in the world of ‘nations’ and ‘civilizations’.

In this light, Kenji Nakagami’s true intention may simply have been to convey, in his own words, that ‘the Land of Darkness is proudly shining’ (free, equal, and highly viable without being tamed by the state or government).

[1] Kenji Nakagami, Kishu: Tales from the Land of Wood and Land of Roots, Kadokawa Bunko, 1980, p. 288.

[2] Ibid, pp. 294-297.

[3] Mircea Eliade, translated by Kyoko Nakamura, The Works of Eliade, Vol. 7: Myth and Reality, Serika Shobo, 1995.

[4] Yonekichi Kondo, Plants and Mythology, Setukasha, 1973, p. 1

[5] Atsuhiko Yoshida, The Origin of Japanese Mythology, Kodansha, 2007, pp. 44-46, The myth of the origin of death is a myth that explains why the human lifespan is shortened; in the banana myth, in the choice between ‘stone and banana’, the ‘stone’ is chosen, and in the Konohana myth, ‘stone and flower’ become an ugly sister-daughter and beautiful sister-daughter respectively. They are transformed and the ‘beautiful sister-daughter’ is chosen and her life span is set by the wrath of god.

[6] Taryo Obayashi, Mythology Genealogy, Kodansha, 1991, p. 291.

[7] Clarissa Hyman, Orange: A Global History, translated by Tomoko Omachi, Hara Shobo, 2016, pp. 133-138.

[8] Pierre Laszlow, translated by Tomoko Teramachi, Citrus: A Cultural History – History and Human Relations, Ittosha, 2010, pp. 239, 240.

[9] Pierre Laszlow, translated by Tomoko Teramachi, Citrus: A Cultural History – History and Human Relations, Ittosha, 2010, p. 237.

[10] Pierre Laszlow, translated by Tomoko Teramachi, Citrus: A Cultural History – History and Human Relations, Ittosha, 2010, p. 240. In this book, the trees in the background are said to be orange trees.

[11] Pierre Laszlow, translated by Tomoko Teramachi, Citrus: A Cultural – History and Human Relations, Ittosha, 2010, p. 297.

[12] Unlike oranges, tangerines and tachibana do not produce white flowers and fruit at the same time as oranges, so the points relating to purity and fecundity shall not be considered.

[13] Taryo Obayashi and Atsuhiko Yoshida, How to Read the Myths of the World, Seidosha, 1998, pp. 222, 223.

[14] Taryo Obayashi, Atsuhiko Yoshida et al, Dictionary of Japanese Mythology, Yamato Shobo, 1997, p. 348.

[15] Taryo Obayashi, Atsuhiko Yoshida, How to Read the Myths of the World, Seidosha, 1998, pp. 192, 193.

[16] Taryo Obayashi, Mythology Genealogy, Kodansha, 1991, p. 264.

[17] Chiwaki Shinoda, World Plant Myths, 2016, Yasaka Shobo, p. 24.

[18] Ibid, p. 25.

[19] Taryo Obayashi, Atsuhiko Yoshida et al, Dictionary of Japanese Mythology, Yamato Shobo, 1997, p. 349.

[20] Ikeda, Masayuki, Mitsuishi Manabu et al, Kumano kara yomu kiki mythology – Nihonshoki 1300 nenki (From the Perspective of Kumano: Kiki Mythology, Nihonsyoki for 1300 years) -, Fusosha Shinsho, 2020, p. 24.

[21] Mutsuko Mizoguchi, The Birth of Amaterasu: The Search for the Origin of the Ancient Kingship, Iwanami Shobo, 2009, p. 60.

[22] Taryo Obayashi, Atsuhiko Yoshida et al, Dictionary of Japanese Mythology, Daiwa Shobo, 1997, p. 349.

[23] Mutsuko Mizoguchi, The Birth of Amaterasu: The Search for the Origin of the Ancient Kingship, Iwanami Shobo, 2009, p. 38.

[24] Taryo Obayashi and Atsuhiko Yoshida, How to Read the Myths of the World, Seidosha, 1998, p. 218.

[25] 26 Taryo Obayashi, The Way of the Sea, The People of the Sea, Shogakukan, 1996, p. 263.

[26]Taryo Obayashi, Atsuhiko Yoshida et al, Dictionary of Japanese Mythology, Daiwa Shobo, 1997, p.198

[27]Kiitumoto Shrine Website: https://wakayama-jinjacho.or.jp/jdb/sys/user/GetWjtTbl.php?JinjyaNo=2021

28 Taryo Obayashi, Atsuhiko Yoshida et al, Dictionary of Japanese Mythology, Yamato Shobo, 1997, p. 224.

29 Taryo Obayashi, Atsuhiko Yoshida et al, Dictionary of Japanese Mythology, Yamato Shobo, 1997, p. 225.

[28] Taryo Obayashi, Atsuhiko Yoshida et al, Dictionary of Japanese Mythology, Yamato Shobo, 1997, p. 84.

[29] Toshio Kikuchi, History of Tokyo Bay, Dainippon-tosho, 1974, p. 40.

[30] Kenichi Tanigawa, Japanese Gods, Iwanami Shobo, 1999, pp. 96, 97.

[31] Taryo Obayashi, Atsuhiko Yoshida et al, Dictionary of Japanese Mythology, Daiwa Shobo, 1997, p. 357.

[32] Taryo Obayashi, Atsuhiko Yoshida et al, Dictionary of Japanese Mythology, Daiwa Shobo, 1997, p. 365.

[33] Ministry of Agriculture, Forestry and Fisheries statistics https://www.maff.go.jp/kinki/toukei/toukeikikaku/yotei/attach/pdf/2021-2.pdf

[34] Kazuyoshi Tuji, Development and issues of Citrus Producing Areas in Wakayama Prefecture, website 2018, (http://www.mikan.gr.jp/report/tenkai.pdf)

[35] Shinichi Nakazawa, The Gift of Pure Nature, Serika Shobo, 1996, pp. 93, 94.

[36] James C Scott, translated by Masaru Tachiki, Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, Misuzu Shobo, 2019, pp. 225-228.

[37] James C Scott, translated by Masaru Tachiki, Against the Grain: A Deep History of the Earliest States, Misuzu Shobo, 2019, p. 229.