Orange Collective

Report on the Venice Biennale 2022 and Documenta Fifteen for the Orange/Mikan Collective (Part 2)

Kinan Art Week Yabumoto Yuto

1 Introduction – Ruangrupa and Ivan Illich

In the 1st part of this Report, after touring the 59th Venice Biennale (23 April – 27 November 2022, hereinafter ‘Biennale’) and documenta fifteen (18 June – 25 September 2022, hereinafter ‘documenta’), I discussed ‘de-anthropocentrism’, ‘Dana Haraway’s philosophy’, and ‘Re-enchantment’. In the 2nd part, I will focus on the content of documenta, with an emphasis on Ivan Illich’s (1926-2002) concept,’Conviviality.’

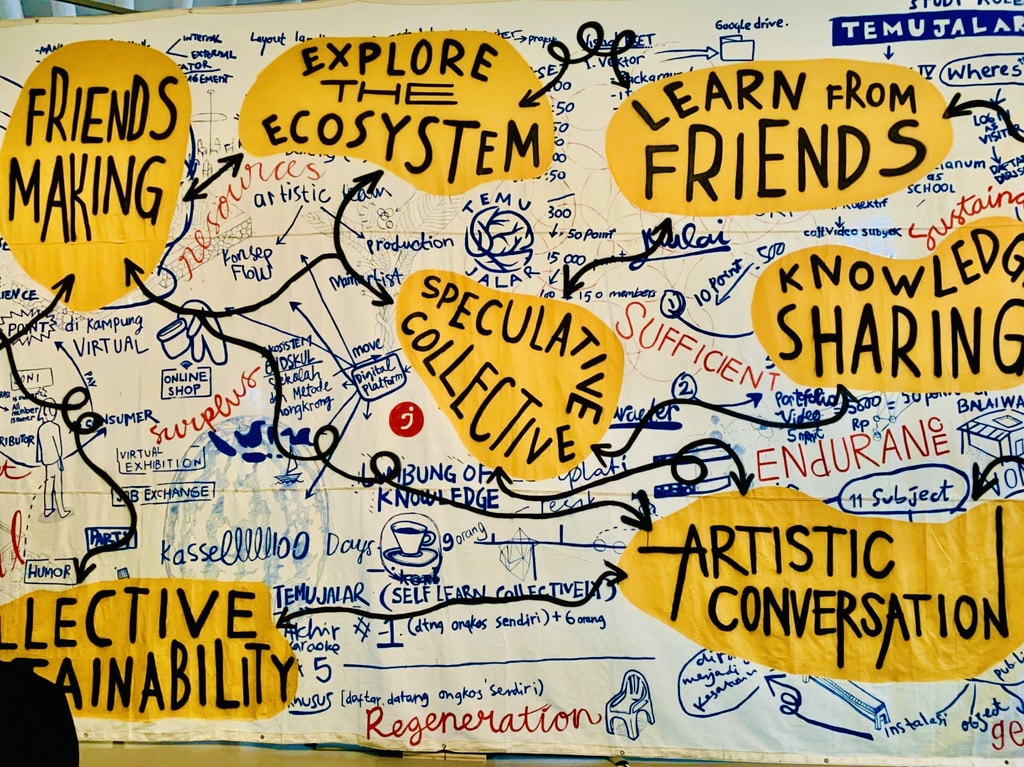

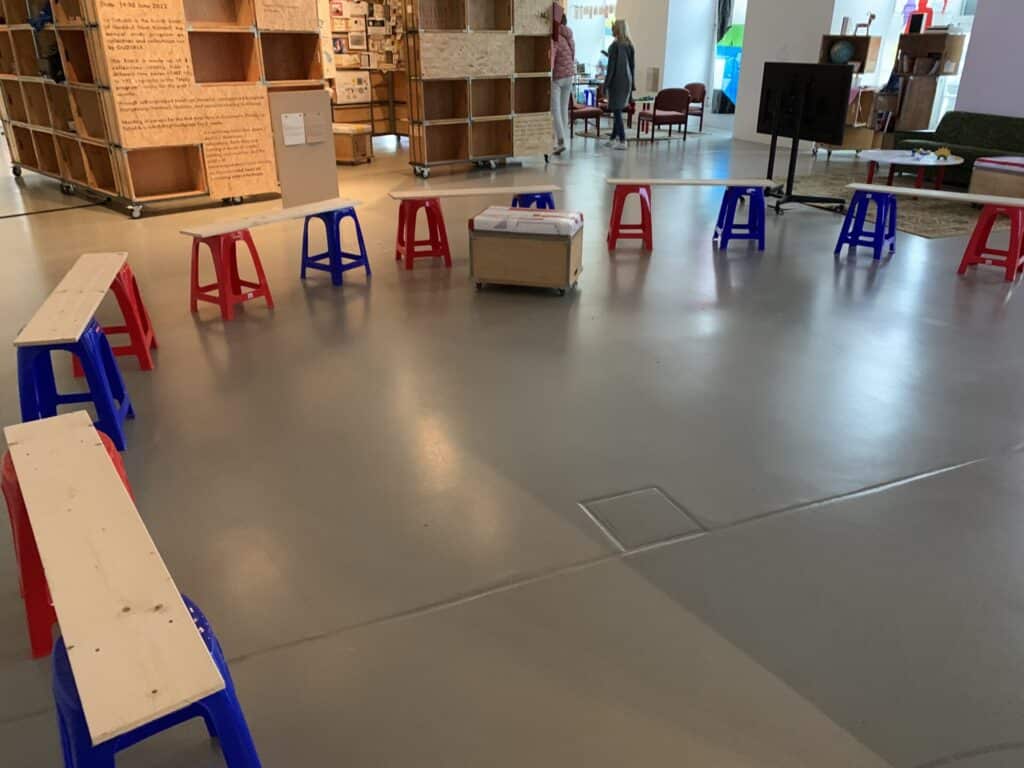

Since the opening of documenta, there have been rather negative reviews in ArtReview[1], The Art Newspaper[2] and Artforum[3]. However, in my opinion, such sentiments were indicative of there being “nothing new,” which I interpret in a positive sense. The festival’s opening was more like a reunion than an exhibition, with old friends and colleagues eating, drinking and conversing in a leisurely manner. The exhibition was not so much a pure viewing of the art works as it was a reunion of former friends, eating a meal, drinking and conversing. The full programme of events, including dinners, concerts, live music, nightclubs, karaoke, saunas (!!!), and so on, made it possible to enjoy a wide range of activities, and was more like a festival than an exhibition. In a sense, this was in line with the intentions of ruangrupa, which advocates “Make friends, not art!”[4]. It was also a valuable opportunity to gain a comprehensive understanding of the activities of art collectives in Africa, South America and elsewhere, whose activities overlap with the practices of art collectives in South-East Asia.

Not a nuclear reactor, but an energised reactor. The meltdown caused by the Great East Japan Earthquake was one of the largest nuclear accidents in history. It triggered a deep-seated distrust of scientifically civilised society that has a history of functioning as one of the key driving forces in the ‘social turn in art’ represented by Tanaka Koki, Chim↑Pom and other artists.[5] Based on this context, a movable sauna that imitates the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear power plant can be deployed at any location around documenta. After talking to each other in the Kassel herbal sauna, we drank Genki tea and documenta beer one after another while inviting further strangers to join the gathering. The people who had entered the sauna earlier–which was energizing and perhaps encouraged friendliness – attracted more new strangers to the sauna as well as to the gathering right outside of it.

Indeed, the concept of ‘Make friends, not art” could provoke the same debate as Claire Bishop, who presented ‘The Social Turn of Art’ and criticized Nicolas Bourriaud’s ‘Relational Aesthetics’ in her paper, ‘Antagonism and Relational Aesthetics. Bishop’s critique was that people will often gather only with those whom they are familiar, and merely construct superficially harmonious relationships with strangers[6]. In our online talk session, ‘Agriculture x Art Collective: Learning from the Case of Itoshima Arts Farm’, our guest speaker, Egami Kenichiro, a Japanese independent researcher, also discussed the ‘Social Turn of Art’, ‘Relational Aesthetics’ and ‘Art Collectives’.

Another criticism would concern whether it is necessary to make a spectacle of the collectives at documenta that are supposed to be practicing and achieving results in ‘vernacular’ places. ‘Vernacular’ is a word that means like ‘indigenous’, and ‘rooted’, but ‘vernacular’ is a term redefined by Illich as something that is autonomous and not subject to institutions.[7]

However, I feel that these criticisms do not need to be taken too literally if we move ourselves away from artistic institutions and look at them from the perspective of a critique of industrial civilisation, which I will discuss later (as discussed in the 1st part, the artistic direction of documenta, ruangrupa has made it clear that they do not work in the context of Western institutions).

2 ‘Ivan Illich’ and ‘Conviviality’.

(1) What is Ivan Illich’s philophophy’?

Illich’s ideas are sometimes said to be old-fashioned, but I believe that they are rather more important today, when the power of ‘technology’ and ‘institutional power’ is even stronger than it was in Illich’s time.

Illich was a philosopher who, despite being an elite member of the Christian world, moved from the Western world to South America, where he continued to criticise industrial civilisation, questioning the ‘human way of life’ and the ‘hope of life’[9]. While running a law firm in a developing Asian country, I have often sympathised with Illich’s philosophy: fed up with many products and services in the name of the ‘public’ such as SDGs and personal data protection, and aware that what we are now doing is falling into ‘Counter-productivity’[10] as defined by Illich. Even though we are aware of how impersonal such services and proposals are, we offer them just the same. Other key concepts, such as ‘Shadow-work’ and ‘Economic sex’ will not be discussed in detail in this report, but Illich gives us hints into the depths of the difficulties of living in modern industrial society.

Illich pointed out that the ‘institution’ behind social services and the ‘power’ of professionals are factors that promote the self-domestication of human beings. Taking schools as one example, he stated that the ‘Institution’ of school limits human freedom and leads to the loss of human autonomy (Illich develops a ‘Deschooling’ theory, which is not detailed here). In order to reclaim humanity from such a society, he criticized all kinds of ‘Institutions’, such as schools and other social services such as transport and healthcare.[11]

Illich also focuses on the concept of the ‘Tool’, which includes ‘Institution’. He states that ‘Tools’ include ’Hand Tools’ that could be used by people’s hands with their will, in contrast to ‘Power Tools’ such as machines that could be ruled by ‘Institutions’ and ‘Technology’. In modern society, heteronomous power tools have reached the point where they dominate thought and society, and thus, we must confront and break away from this domination by rethinking ‘Tools (hand tools)’.[12] In addition, I believe that there is significant overlap between Illich’’s thought and the practices of ruangrupa, which will be discussed below.

(2) What is ‘Conviviality’?

Conviviality is a term defined by Illich in his critique of industrial civilisation. It is a word derived from Spanish, often translated into Japanese to mean ‘self-reliant symbiosis’, as strictly speaking, ‘conviviality’ does not mean ‘symbiosis’, in Latin languages. In the words of Illichi researcher Yamamoto Tetsuji[13], ‘self-reliance’ and ‘symbiosis’ are contradictory terms in a sense, but this ‘conflict’ is the key to understanding Illich, and ‘Conviviality’ is “the structural coexistence of opposing things with each other, not exclusively, but in a pluralistic balance”.[14]

For example, when a missionary from another part of the world visits the countryside where vernacular people have lived, the content of the dialogue with the missionary might be recognised as the new wisdom of the local people. In this case, the expression would be “Convivial” to the locals, as the word is used in the Latin world regularly. In other words, multiple incompatible things altruisticly worked for good, momentarily, as something was accepted voluntarily.[15]

In fact, the Asian collectives I know seem to prefer a kind of ‘Come-and-go-relationship’[16] neutral relationship rather than a close relationship. The members themselves are fluid and open, and there is basically no compulsion or restriction on participation. It feels as if autonomous individuals are only interacting with others momentarily and temporarily. In this sense, whether it is a spectacle or not, it would be good if the artists exhibiting at documenta could create a ‘Convivial’, accidental and temporarily good state of affairs with the ‘Others’ in Kassel. As regards the debate on the ‘Aesthetics of Relations’ that the art reviews claims about documenta, the criticism regarding a the ‘Stable Symbiotic’ relationship may not apply, since the artists are not looking for a stable symbiotic relationship in the first place, but rather embracing their short-term, unintentionally coincident presence at the site.

(3)Techinical Art to Restore Tools of Convivality

Illich also states that in order to regain ‘tools for conviviality’, it is necessary to (1) The Demythologization of Science[17] (to break away from excessive trust in scientific knowledge), (2) The Rediscovery of Language[18] (to break away from the industrial civilisation’s co-option of language) and (3) The Recovery of Legal Procedure[19] (to recover the sense that one is involved in public law and discourse), stating that these three elements are all necessary.

The ‘Demythologization of Science’ will be omitted here, as I believe it has already been adequately described in the discussion of ‘De-anthropocentrism’ and ‘Re-enchantment’ in the 1st part of this report.

With regards to the ‘Rediscovery of Language’ and the ‘Recovery of Legal Procedure’, the concept of ‘Project-based democracy’ is, in my view, crucial. ‘Project-based democracy’ is a term defined by the Italian philosopher r Ezio Manzini as a place where the commons (which is, incidentally, one of Illich’s main concepts) and the trust relationships that govern it is described as a process where autonomous people bring in ideas and projects, and make decisions in a constant and ongoing dialogue in order to create a trust relationship.[20] This overlaps with what can be glimpsed in the practices and interviews with ruangrupa.

First, with regard to the ‘Rediscovery of Language’, Illich points out that modern language is radically monopolised by industrial civilised society, and that in this society, most words are used in possessive language. So, it is necessary to review our use of words from an action-oriented linguistic sense.[21] There is a need to switch to action-oriented language usage, such as ‘learning something’ at school instead of ‘Receiving educational services’, ‘Traveling somewhere’ from a station instead of ‘Receiving public transport services’, and ‘Working’ at work instead of ‘Having a job’. In the current education system, the phrase ‘I want to learn’ is naturally transformed into ‘I want to be educated’. So we need to distance ourselves from the ‘System’ once and for all, and through project-based democratic processes, see through these and regain autonomous language usage. The dialogue of ruangrupa, described in the 1st part, is indeed the process for the ‘Rediscovery of Language’, and the place for this is probably not the so-called formal meeting rooms, but rather places where people gather, such as the dining halls, karaoke rooms and saunas.

Next, Illich states that the ‘Recovery of Legal Procedure’ has become a heteronomous tool for the judicial system and police power to comply with industrial civilisation. Therefore, he states that it is important to take back ‘appropriate legal procedures’ as a tool that is different from the laws and forms that go through existing political processes, such as the electoral system.[22] In this context, one’s own decision-making in organizations and communities is also important.

Relatedly, the American anthropologist David Graeber (1961-2020) points out that democracy was not born in the West (Athens), but rather that the unanimity system is the basis of democracy (not subject to the principle of majority rule)[23]. In this regard, when I interviewed Alexander Supartono to discuss Taring Padi, and Ade Darmawan of ruangrupa, they indicated that for organisational decision-making, they do not follow the majority voting system, but rather the unanimity system. In other words, although it may be inefficient, the decision-making process cannot proceed unless each person makes a decision. I am not sure whether their practices are influenced by Ilich, but I think that this process is the practice that corresponds to the ‘Recovery of Legal Procedure’ of human beings.

The Indonesian art collective Taring Padi, formed in 1998, is an art collective that emerged from the movement against the Soeharto regime. It developed woodblock prints, posters and murals in opposition to the dictatorship.[24] It should be noted that the ‘People Justice’ at Fridericianum Plaza was covered up and removed over issues related to anti-Semitism[25] , causing a major stir over ‘freedom of expression’. For more information on Taring Padi, see “Mikan Dialogue vol.1 Text Archive (Part 2)” where Egami Kenichiro describes Taring Padi in more detail.

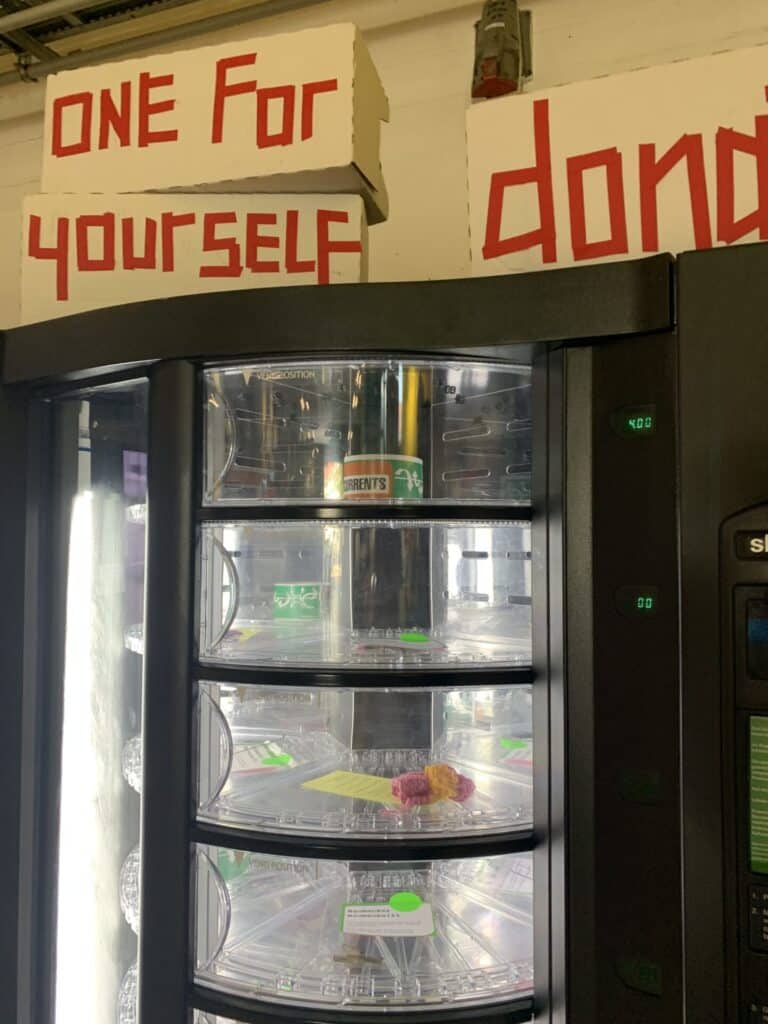

In addition, ruangrupa’s activities are also related to Ilich’s criticism of Monetary Society, and De-schooling. For example, some of their works were sold in vending machines at documenta, where there was no set price, and some were paid as a donation, based on the willingness of the purchaser. In addition, according to Ade, these sales are stored in the lumbung (communal rice barn), and the system seems to be designed to give back to the whole community. Talking to a member of ruangrupa, he said, “I don’t really know the price of art that markets and galleries put on it. I want you to pay attention to the small pieces of art that are here”. I think he means that he wants people to feel the value of the ‘Hand Tools’ that are created and used in daily life and expression, and which promote people’s autonomy in their own lives, rather than works sold in the so-called centers of art, such as galleries.

In addition, ruangrupa’s perspective is also enthusiastically focused on “a place of learning.” It is clear from the fact that RURU KIDS, which has playset facilities, production facilities, library facilities, daycare centers, study spaces, etc., is located on the first floor of the Fridericianum Museum, which is the most important place in documenta.

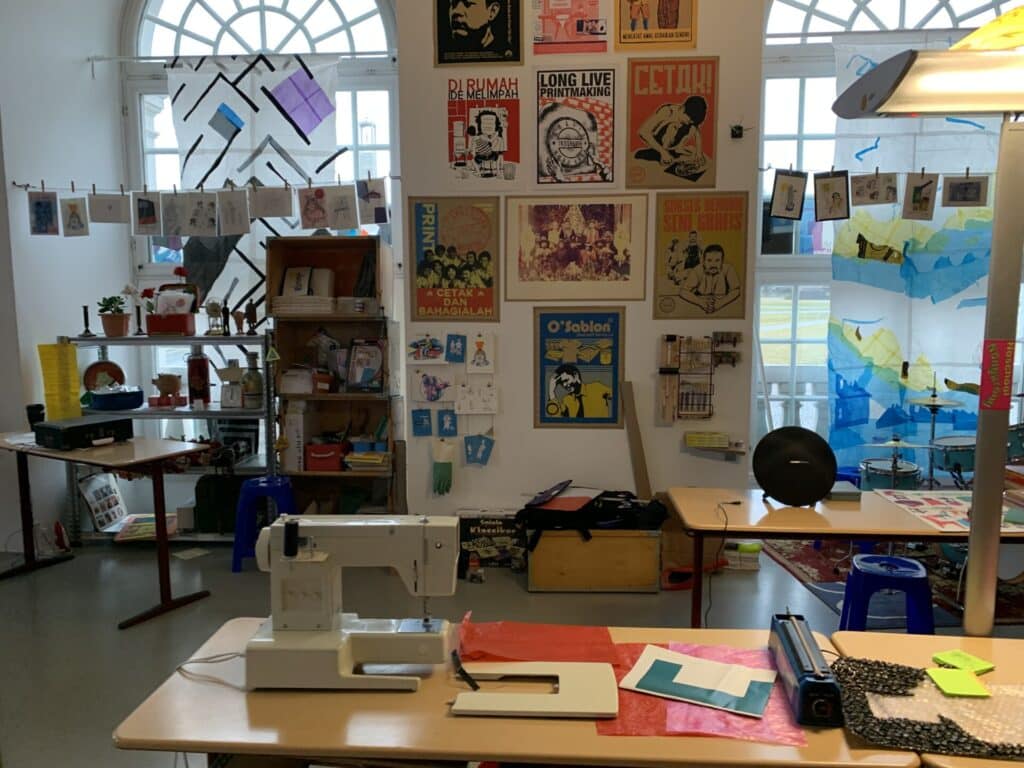

The exhibition captions at the entrance to Gudskul, also on the ground floor of the Fridericianum Museum are, surprisingly, aligned with the height of a child’s eyes. It is there that the content of the practices in GudkulGood School is organized. It includes places for reading and dialogue, play areas and access to hand tools such as sewing equipment.

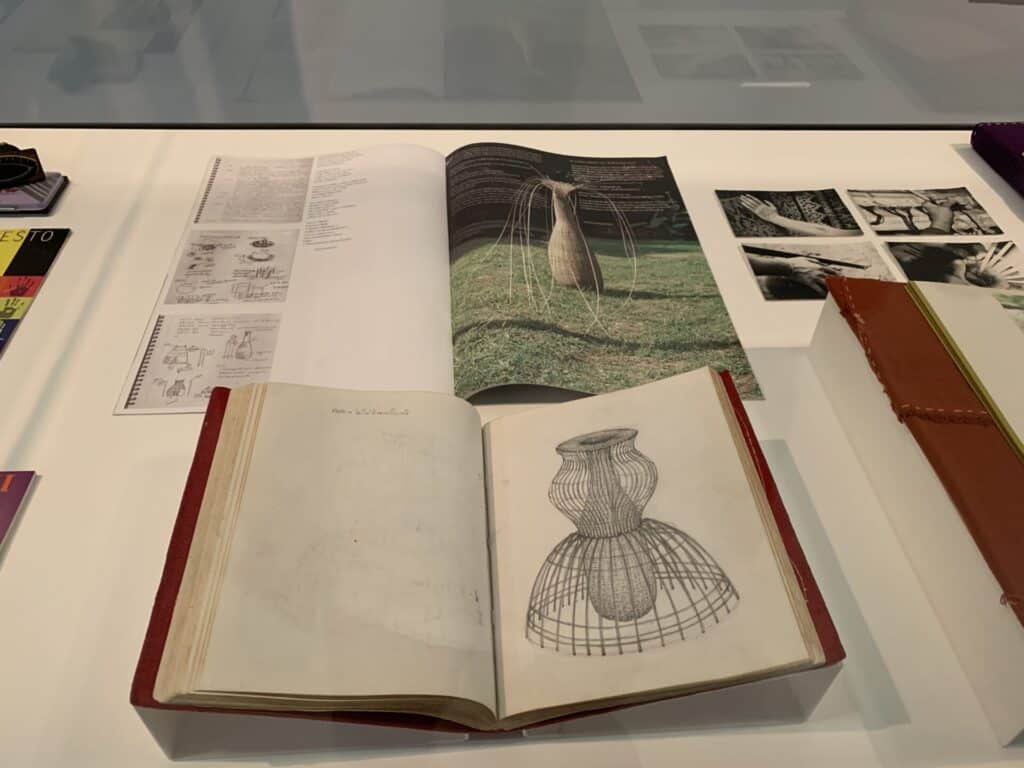

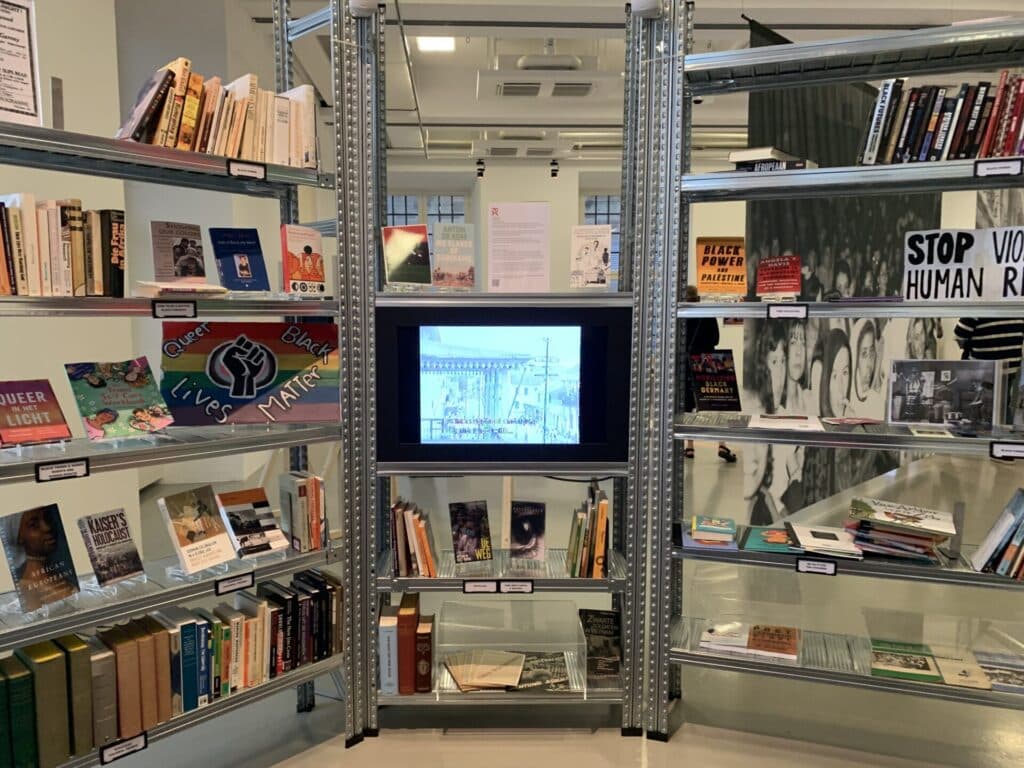

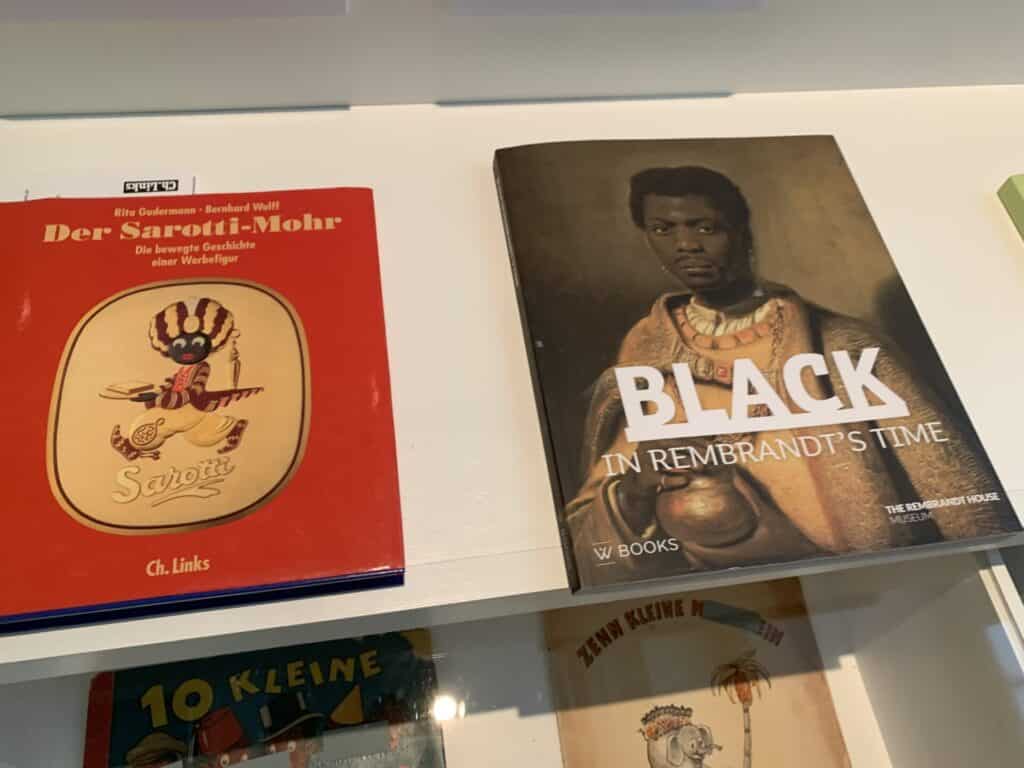

Furthermore, on the 2nd floor of the Museum, archival exhibitions such as Asia Art Archive, The Black Archives and Archives des Lutes des Femmes en Algerie were on display. The archives may serve an important function in connecting the past with the present and in understanding the present location of vernacular places and the people who live there.

As is clear from the above-mentioned practices of ruangrupa, the group is probably keenly aware that transcending existing systems and creating alternative ‘self-learning’ and ‘self-projecting’ places is of paramount importance in overcoming industrial civilisation. Whether it deviates from the artistic context, or whether their art is criticized as being just a unification of their fellow members, if a “Convivial” movement is produced, especially in our time of increasing power of “institutions” and “technology” (at least that’s how I feel), such works may be valuable for their practical value.

(4)The Art of “Co-operation”

Finally, the word ‘Conviviality’ is assigned to ‘autonomous co-operation’, but what does ‘co-operation’ mean? Based on the discussion so far, I believe that it is “the structural coexistence of self, other and opposites, and the ‘creation of something together’ while balancing each other in a pluralistic way”. What I feel after viewing the documenta exhibition is that anyone, anywhere, can ‘create’ something. In other words, using the technique of ‘art’, it is naturally possible to create and express oneself immersively, even if one is not a member of a privileged class or a so-called genius. Although it may not be possible to say that all the works at documenta were created in a state of ‘Conviviality’ (autonomous co-operation), documenta provided many good examples of collective techniques and practices in which the self and others create a general sense of ‘Conviviality’.

For example, the Cambodian art collective Sa Sa Art Projects[26] is essentially run by members with no professional art education. Concept-making and production, such as paintings, are often divided between the members, who are all autonomous artists, researchers and curators, but work together in dialogue based on their individual strengths. In exhibitions, too, the presence of the curator is not particularly explicit, and the characteristics of ‘creating together and making exhibitions together’ are demonstrated through the involvement of autonomous others.

This is the documenta edition of the ‘Master of Land and Water’ exhibition, which was also on show in Phnom Penh, Cambodia. The writer’s collection of Khvay Samnang’s “Popil and Lim Sokchanlina’s “Letter to the Sea” were on display. As examples of Sa Sa Art Project’s loose relationship with others, the works of Vietnamese artist Ngoc Nau, who will be participating in a future Sa Sa Art Projects residency, and Myanmar artists Aung Ko and Nge Nay, who have participated in the past, were also on display. While it could perhaps be criticised as “I don’t know what I’m looking at!” at documenta, this exhibition was probably considered relatively easy to view at documenta, which has been criticised for its “I don’t know what I’m looking at!” nature.

Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts and Culture[27], on the other hand, placed a skate rink at the center of its exhibition. Baan Noorg is the name of a village in Nongpho, Thailand, and the art collective that has developed there. Baan, in Thai, means ‘home’ and Noorg means ‘outside’, and it feels as if it is thinking about the relationship between ‘inside/outside’. In this exhibition, people who come to documenta and enjoy skating together for a time are an important element of the work, and I think this is an exhibition that is ‘created together’, temporarily, with other people.

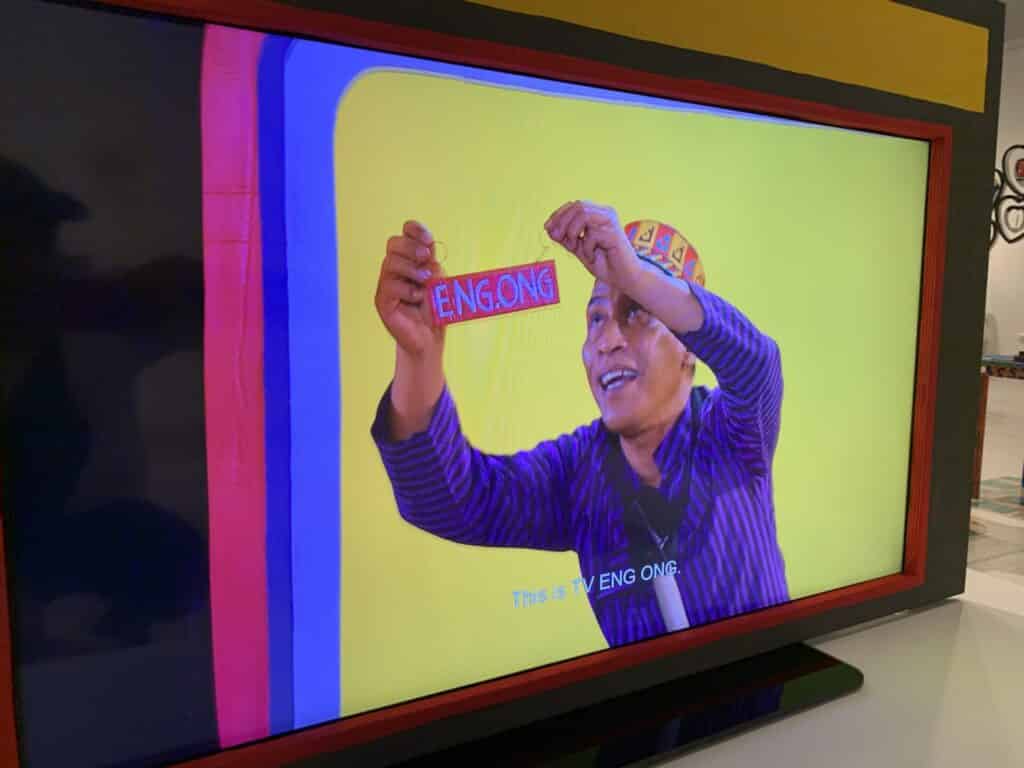

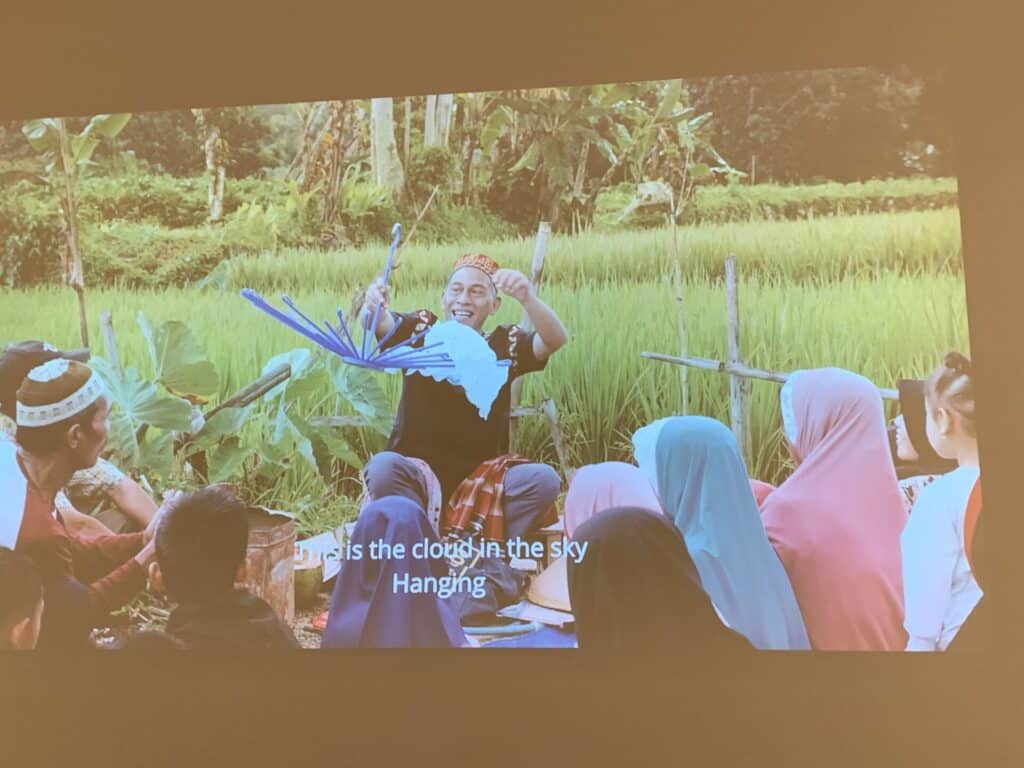

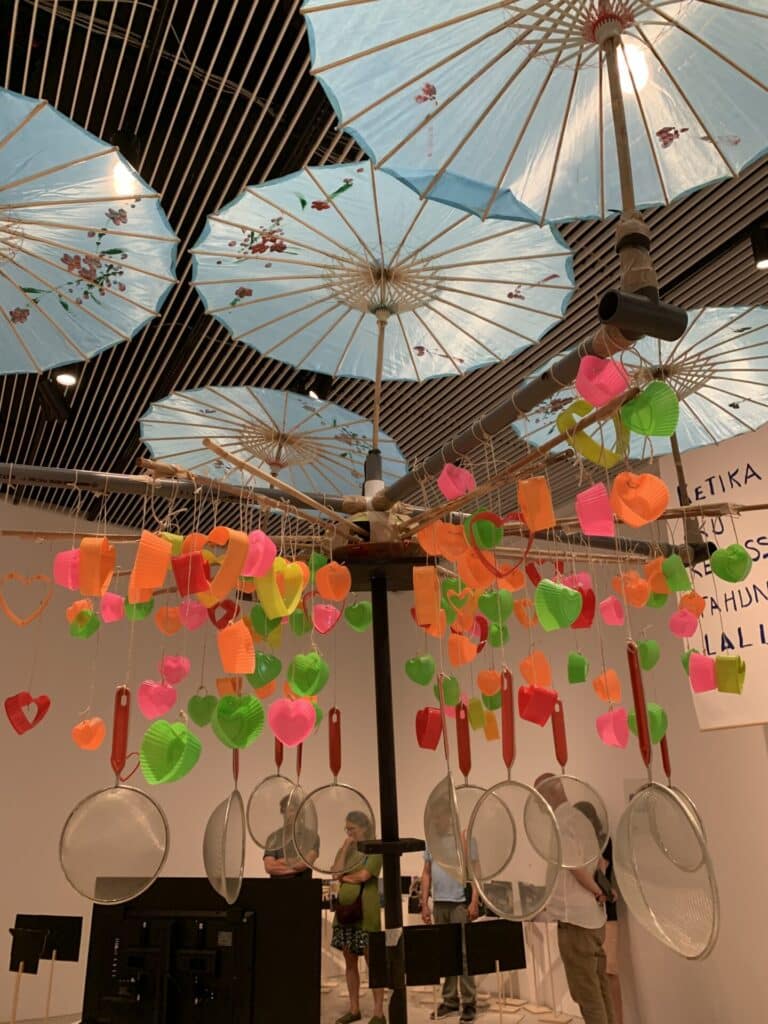

Also of particular interest was the practice of Agus Nur Amal. Agus is an actor and storyteller from Aceh, Indonesia. Agus tells the myths and legends of Aceh with humor, using everyday ‘hand tools’ such as frying pans, clothespins and rubbish bags. He then uses these ‘tools’ to create ‘art’ that transcends the boundaries of whether the work is a child’s toy, a chair, a lamppost or a work of art. In other words, I was reminded once again that art is something that anyone can create and enjoy.

The artist has been conducting lectures in different parts of Indonesia, covering politics, the environment, peasant life, etc. The video showed Agus’ amusing talks on indigenous novels, legends, etc., and the audience’s responses, as well as an installation using everyday objects that would have been made on the spot, which seemed to be full of hints for enjoying everyday life in our own hands.

Kiri Dalena, on the other hand, is an artist from the Philippines known for her work on injustice and social inequality in her country. She also runs an art collective of her own and is engaged in resistance activities in the form of gathering citizen’s voices in the Philippines. Pila, which was exhibited at documenta, could be considered an exemplary work ‘produced with’ strangers.

According to field interviews with Kiri, the exhibited work Pila is a video work using five cameras set up in front of her house, which rearranges the sounds of others walking down the street and their everyday lives. It presents the collective consciousness and unconsciousness in the midst of Covid 19.

Finally, we turn to the activities of Nha San Collective[28], the place where I spent the most time during my stay at documenta. Nha San Collective is an art collective founded in 2013 in Hanoi, Vietnam. The name ‘Nha San’ refers to the traditional wooden houses of the Hmong people and to Nha San Studio, which, before being forced to close by the authorities in 2011, was a very important place, being the first contemporary art space in Vietnam. Nha San Studio was founded in 1998 by Nguyen Manh Duc and curator Tran Luong, and is now run by Nguyen Phuong Linh, daughter of Nguyen Manh Duc. She has taken over the space and is running the operation.[29] .

In WH22, the venue for documenta, there was a garden (!) for Vietnamese refugees, immigrants and their children who were separated during the Vietnam War. Tuan Mami, one of the founders of Nha San Collective, entered Kassel in February 2022 and began to build this garden. The dining room and accommodation facilities, as well as the garden, were handmade, and about 20 members lived there (!!). They even ate the vegetables and fruit grown in the garden. I doubted my eyes: ‘Is this really Kassel?’ Indeed, Mami even planted Vietnamese plants brought in, which were grown in this garden and carefully nurtured. This mirrors the experience of Vietnamese refugees who fled to Germany, in a sort of illegal way, during the Vietnam War era. Vietnamese refugees who are ‘Radicant’ (a concept to be discussed in the part 3 of this Report)[30], as Nicolas Bourriaud, described them, are as strong as the plants growing in their garden and have their roots in the land of Germany. The beings gathered and generated in that garden, transcending human/plant boundaries, live powerfully and autonomously. I was so moved by the sight that I could hardly leave the place. I felt that this is a wonderful practical art that was “generated by Co-operation” with plants and nature as well as Vietnamese people

Tuan Mami emerges from the lush vegetation. These plants are vegetables and herbs from their homeland, Vietnam, but it is difficult to bring Vietnamese plants and vegetables into Germany, So, it is not easy to grow and make food with these native ingredients on their dining table in their non-native country. In human history, humans, animals and plants have migrated together, so why is this not allowed in modern times? In the colonial era, the Western world exported sugar cane and other plants and gained great wealth, one of the immigrant members said. It feels as if I have come to the home of the Hmong (Nha San), an ethnic minority group that has repeatedly migrated and dispersed, and that this overlaps with the feeling I had when I visited and had a dialogue with a charcoal burner living in the forests of Kumano, Wakayama. (The column: The future is coloured by pine smoke ink -Current situation and challenges in the ink industry –)

Based on the positive example of Nha San Collective, as mentioned in the previous section, ‘Growing plants (mandarins)’ is a technique (art) for living well’. At the Orange/Mikan Collective, we would like to make use of this experience and prepare exhibitions and workshops so that we, as others, can now create a ‘Convivial’ state of goodness with vernacular places and the people who live there.

The next, the presence of ‘Botanicals’ is attracting attention, as seen in the practice of Nha San Collective. Based on the discussions I have described so far and the content of both the Biennale and documenta exhibitions, we will go one step further and discuss the limits of the animal systems and the potential of the ‘plant system’ of Kinan/Kumano region and the entanglement of humans/plants.

[1] Documenta 15 Review: Who Really Holds Power in the Artworld

https://artreview.com/documenta-15-review-who-really-holds-power-in-the-artworld-ruangrupa/

[2] Documenta Drama: the six most controversial (and confusing) things we saw at the Kassel exhibition

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2022/06/21/documenta-15-most-controversial-kassel-exhibition

[3] BAH LUMUNG https://www.artforum.com/diary/kristian-vistrup-madsen-at-documenta-15-88761

[4] Documenta fifteen Official Guidebook, p. 9.

[5] Yamamoto Hiroki, Decolonising Techniques (Art): on the Potential of Socially Engaged Art in East Asian Postcolonial Contexts.https://note.com/misonikomi_oden/n/n615ecc796b1e

[6] Hoshino Futoshi, Aesthetic Practices, Suiseisha, 2021, pp. 122, 123.

[7] Yamamoto Tetsuji, Ivan Ilyich – The Idea of ‘Hope’ Beyond Civilisation, 2009, EHESC, p. 64.

[8]Wikipedia, “Ivan Illich.”

https://ja.wikipedia.org/wiki/%E3%82%A4%E3%83%B4%E3%82%A1%E3%83%B3%E3%83%BB%E3%82%A4%E3%83%AA%E3%82%A4%E3%83%81

[9] David Cayley (ed.), Ivan Illich in Conversation, translated by Ryuichiro Usui, Fujiwara Shoten, 2006.

[10] The creation of outcomes contrary to what the system has set as its goal (Tetsushi Yamamoto, Ivan Ilyich – The Idea of ‘Hope’ Beyond Civilisation, 2009, Publications Office of the Institute for Advanced Studies in Cultural Sciences, p. 79). Examples of such events include: if people go to school, their motivation to learn is reduced; if they go to hospital, illnesses are created in the opposite direction (i.e. medical-derived diseases); if traffic is made faster, traffic jams, etc. are created and travel time increases even further, etc.

[11] Yamamoto, Tetsuji, Myths of School, Medicine and Transport: A Critique of Modern Industrial Society – Towards a Convivial World, 2021, EHESC, p. 9-14.

[12] Yamamoto Tetsuji, Ivan Ilyich – The Idea of ‘Hope’ Beyond Civilisation, 2009,EHESC, p. 74-78.

[13] Yamamoto Tetsuji, Myths of School, Medicine and Transport: A Critique of Modern Industrial Society – Towards a Convivial World, 2021,EHESC , p. 346.

[14] Yamamoto Tetsuji, Ivan Ilyich – The Idea of ‘Hope’ Beyond Civilisation, 2009,EHESC, p. 209.

Convivial World, 2021, Publications Office of the Higher Institute for Cultural Sciences, p. 321-329.

[15] Ibid, pp. 74, 75.

[16] Amino Yoshihiko, Mugaii, Koukai, Raku – Freedom and Peace in the Japanese Middle Ages, Heibonsha, 1996.

[17] Ivan Ilyich, translated by Kyoji Watanabe and Risa Watanabe, Tools for Conviviality, p. 190-195.

[18] Ibid, p. 195-202.

[19] Ibid, p. 203-217.

[20] Ezio Manzini, translated by Anzai Yosuke andYaegashi Fumi, Design, When Everybody Designs: An Introduction to Design for Social Innovation, BNP, 2020, p. 159-161.

[21] Yamamoto Tesuji, Ivan Ilyich – The Idea of ‘Hope’ Beyond Civilisation, 2009, EHESC, p. 229.

[22] Ibid, p. 230.

[23] David Graeber, translated by Daisuke Kataoka, There Never Was a West: Or, Democracy Emerfes From the Spaces in Between n’, Eibunsha, 2022, p. 43-47.

[24] Hirota Midori, New Strategies for Contemporary Art: Art Collectives – When Artists Create Organisations, p. 104, 105. https://rci.nanzanu.ac.jp/jinruiken/publication/item/ronshu6_05%20Hirota.pdf

[25] ‘Documenta 15 covers up exhibition work criticised for anti-Semitism. The unending uproar over ‘freedom of expression'”, ARTnewsJAPAN, 24 June 2022. https://artnewsjapan.com/news_criticism/article/280

[26]Aura Contemporary Art Foundation, ‘Lyno Buth: 10 years of supporting contemporary art in Cambodia’.

https://aura-asia-art-project.com/artists/vuth-lynoten-years-of-supporting-contemporary-art-in-cambodia/

[27] Baan Noorg Collaborative Arts and Culture website (https://www.baannoorg.org/)

[28] Nha San Collective website (http://nhasan.org/)

[29] For a detailed genealogy of the history of contemporary art in Vietnam and the history and activities related to Nha San Collective, see the interview byEgami Kenichiro, ‘The reception of “contemporary art” in Hanoi and the two “Nha San (houses)”‘, available at http://scene-asia.com/ja/archives/692.

[30] Nicolas Bourriaud, translated by Takeda Hironari, Radicantn, Filmart, 2022.