Orange Collective

Report on the Venice Biennale 2022 and Documenta Fifteen for the Orange/Mikan Collective (Part 1)

Kinan Art Week Yabumoto Yuto

1 Introduction – Beyond Re-enchantment

Among the ‘world’s three major art festivals–the Venice Biennale, documenta and the Munster Sculpture Project–the 59th Venice Biennale (Dates: Apr. 23 – Nov.27, 2022[1], hereafter ‘Biennale’) has been postponed by one year to take place at the same time as documenta fifteen (Dates: Jun.18 – Sep. 25 2022[2], hereafter ‘documenta’). This report is divided into three parts, in the first I will report these two world-class art festivals I toured, then analyse their content and characteristics mainly from an anthropological perspective, and finally discuss how learnings from them can be reflected in the practice of our ‘Orange Collective’ in the future.

(1) Overview and Characteristics of the 59th Venice Biennale and Documenta Fifteen

Firstly, the Biennale is curated by Italian curator Cecilia Alemani, and the title of the exhibition is The Milk of Dreams, inspired by Surrealist writer Leonora Carrington (1917-2011)’s picture book of the same title. The exhibition consists of three themes: ‘the representation of bodies and their metamorphoses’, ‘the relationship between individuals and technologies’ and ‘the connection between bodies and the Earth’.[3] The exhibition is oriented towards rethinking our relationship with technology and natural ecosystems, as well as transcending dichotomies such as human/non-human, male/female and nature/culture. Of particular note is the fact that out of 213 artists from 58 countries, 90% of the participants are gender non-conforming artists who do not conform to old stereotypes of gender. The use of the term ‘gender non-conforming‘ was undoubtedly influenced by the feminist science theory of Donna Haraway (1944-), discussed below. The Biennial attempts to rethink ‘Re-enchantment’ using this feminist theory. [4]

https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/statement-cecilia-alemani

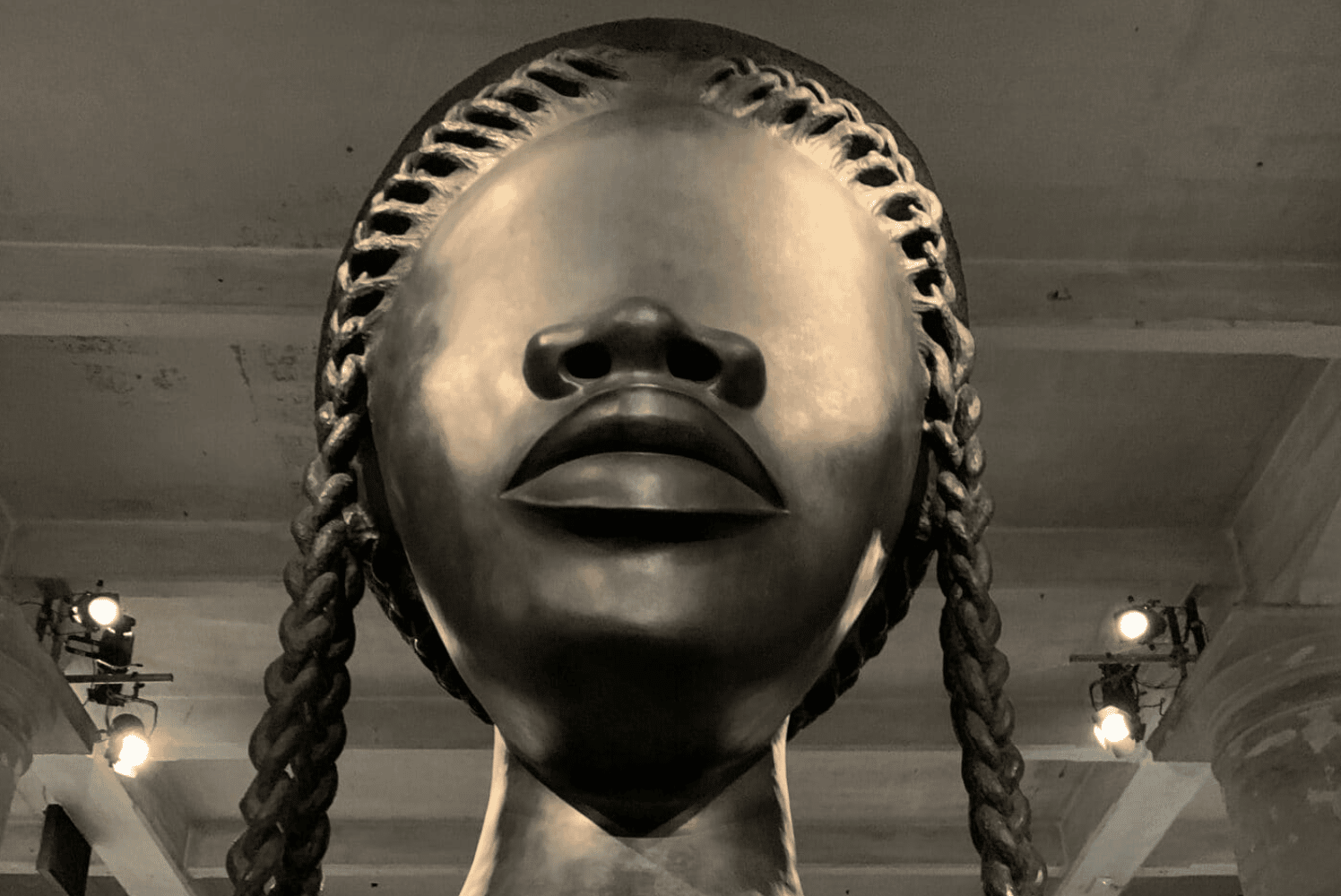

Large sculptural work showing the body of a black woman without eyes. The costume is reminiscent of the abodes of the indigenous people and their sanctuaries. The cornrow ends are adorned with shells, which were tools for witchcraft and were used as currency for slaves in the past.

On the other hand, for the first time in its history, the selected artistic director for documenta’s exhibition came from Asia. The Indonesian art collective ‘ruangrupa’ was the artistic director, and the exhibition was named ‘lumbung’, which means ‘communal rice barn’[5]. The official documenta guidebook states that “We invited Documenta back, asking it to be part of our journey”[6] The key question is whether the exhibition can be realised using the same methodology as usual, without being restricted by existing Western, art history and institutional system, etc.

During my stay in Kassel, I had the opportunity to interview Ade Darmawan, an exhibiting artist at Kinan Art Week 2021 and key member of ruangrupa[7]. He stated that, “In order to build lumbung as a common property, we had plenary meetings at the level of hundreds of artists and related persons, where we discussed what kind of ecosystem we should build and worked out planning the events, exhibition content and even the profit-sharing mechanisms for the items sold.” Their methodology is a clear departure from the top-down curation of the past, and is discussed in the part 2 of this series.

Gudskul, a collective built jointly by ruangrupa, Serrum and Grafis Huru Hara. Gudskul aims to provide a space for open learning, while re-verbalising/reconstructing knowledge, science, technology, etc.-which are prescribed or used only by institutions and specialised fields–for not only by elites and experts, but also for diverse people living in society. The paintings are a trajectory of their practices, values, structures, ecosystems and paths of thought, and provide a glimpse of the roots of the exhibition’s ideology.

(2) Beyond ‘Anthropocentrism’

A common thread in both the Biennale and documenta exhibitions is a perspective on ‘De-anthropocentrism’. During my stay, I toured modern art museums in Italy and Germany, and although I was overwhelmed by their stately histories, most of the works depicted only ‘monotheistic gods’ or ‘humans’. In responding to the contemporary global environment and absurdities, the key challenge is how to transcend the boundaries of Cartesian Western dualisms such as human/non-human, white/non-white, male/female, human/machine, nature/culture, spirit/body, etc.

Both the Biennale and documenta responded to this challenge by drawing heavily on the work of artists and collectives from non-Western regions. Whereas the Biennale’s approach was in line with the history of ‘art’–Romanticism, Surrealism and Enchantment–this documenta, as ruangrupa makes clear, deviates from the Western ‘art’ system, an approach that is bound to attract much controversy. I will examine the art of ruangrupa from the perspective of an existing art history framework, that of ‘Conviviality’ (Ivan Illich, 1926-2002), as well as from my own perspective having lived for a long time in developing Asian countries without any professional art education.

Furthermore, in viewing both exhibitions, there seemed to be a large number of works related to ‘plants’. As with Haraway’s ‘Cyborg’, which will be discussed below, plants have been explored in the past by our collective in “Orange Democracy -What is Collectivism.” As mentioned in the previous section, plants are able to internalise other individuals within themselves through grafting and other means. In this context, “the Plant Turn” is of interest in the context of anthropology, and “The Plant Turn” will be discussed in detail in the 2nd part of this series.

To summarise the above, four characteristics of works from the Biennial and documenta which will explore in relation to anthropocentrism are: (1) the ‘Donna Haraway philosophy’, (2) ‘Re-enchantment’, (3) ‘Conviviality’ and (4) ‘the Plant Turn’, which will, respectively, be examined in this report.

2 ‘Donna Haraway’ and ‘Re-enchantment’

(1) Donna Haraway and multispecies anthropology.

“Human nature is an interspecies relationship[8]”− Anna Tsing

The writer’s beloved book provides an opportunity to rethink society through ‘matsutake mushroom hunting’, from the perspective of matsutake mushrooms, to see what it means for human and non-human beings to ‘live together’.

The cover illustration for Matsutake, “Homage to Minakata (2011)”, was drawn by artist Hiromoto Naoko from Tanabe City in the Kinan region of Wakayama, as a tribute to the great scholar Minakata Kumagusu, who was born in Kinan. It seems that multi-species anthropology and the philosophy of Kinan have something in common.

Multispecies anthropology, as described above by the American environmental anthropologist Anna Tsing (1952-), is a discipline that rethinks what it means to be human in terms of the intertwining of humans with other species (animals, plants, viruses, machines, spirits, etc.). Both the aforementioned ‘Conviviality’ and ‘Multispecies Anthropology’ are important analytical frameworks that go beyond western anthropocentrism. In particular, multi-speeches anthropology is said to have emerged under the strong influence of feminist science anthropologist Donna Haraway,[9] .

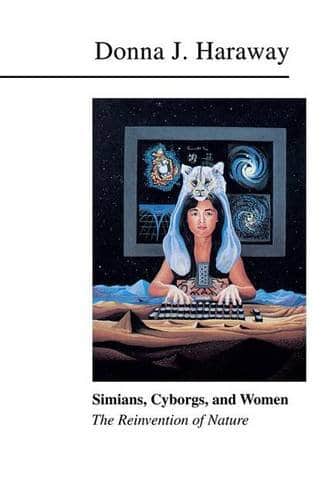

And there is no doubt that Haraway’s ideas have strongly influenced the Biennale. Haraway is best known for books such as “Cyborg Manifesto (2000)” and “The Companion Species Manifesto (2013)”, which present a strong critique of Western values and their violent nature.Cyborg Manifesto is a shocking thesis that begins with ‘We are all cyborgs[10] ‘ and ends with ‘I would rather be a cyborg than a goddess ‘[11]. In the thesis, the term ‘Cyborg is a cybernetic organism, a hybrid of machine and organism, a creature of social reality as well as a creature of fiction.[12] .

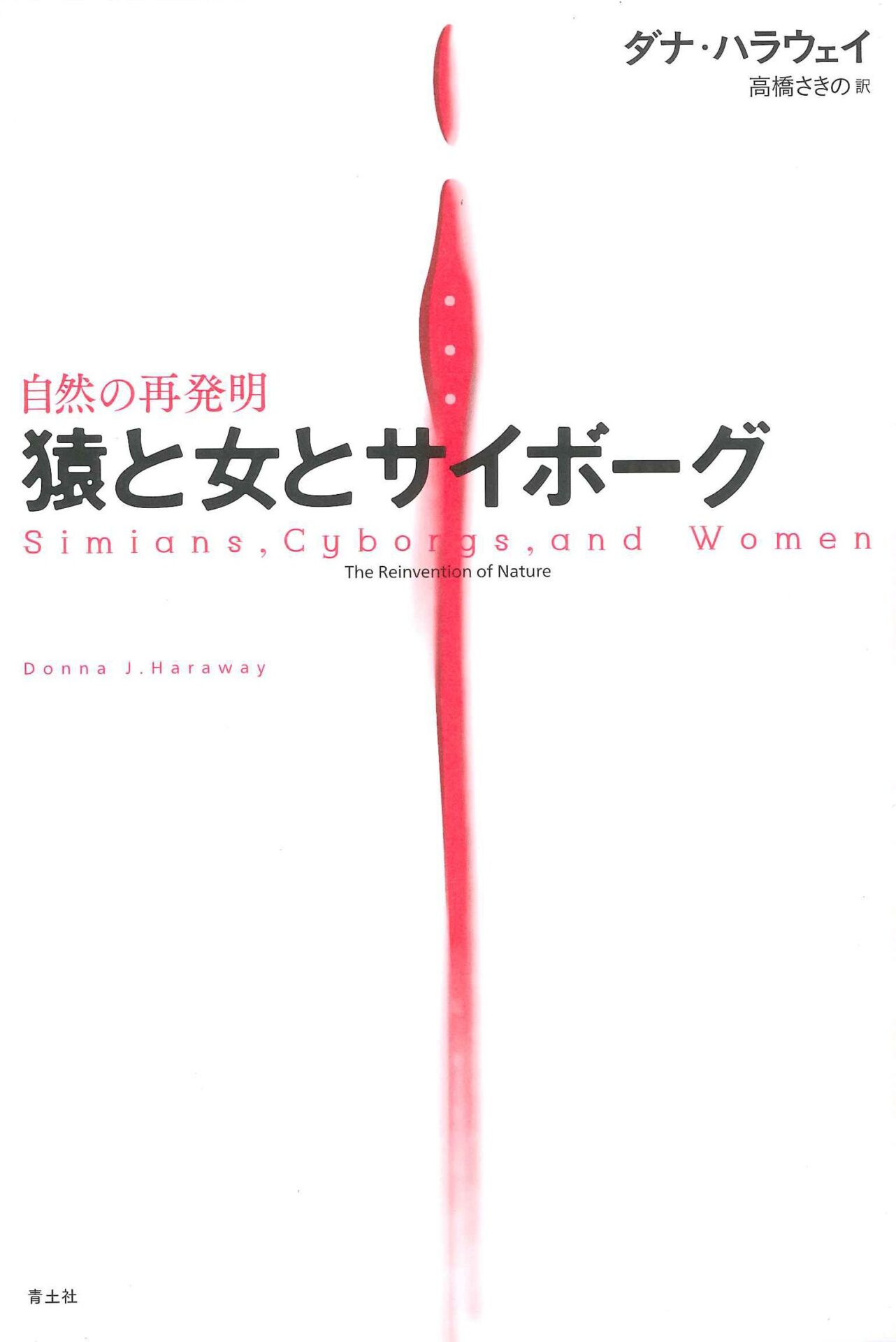

As in this cover picture, cyborgs are generated through the intertwining of various human and non-human (opportunity, animals, ghosts, etc.) entities, and like plants, it is unclear which parts are ‘subject/object’, ‘whole/part’ or ‘centre/periphery’. In this sense, it conveys the importance of being aware that we live, in entanglement, with an awareness of ‘Partial Connections (Marilyn Strathern)’ rather than placing importance on wholeness.

In the thesis, “Coloured Women” are considered the lowest level of reproduction (reproduction/labor) in the social structure of multiple identities, not only in the “house” that governs patriarchy, but also in industrial society due to the increase of women workers (the “feminisation of the Labor Force”[13]), where “female labor is the first word of the machine” (Capital, Vol. 1, Chapter 13), in which they can be categorised as a low-value labor force and treated like female machines.[14]. The sculptures by Simone Leigh (introduced at the beginning of this report), and the beautiful, sad images by Thao Nguyen Phan represent fragments of this history of violence.

Starting from the Mekong Delta, the deep history and small love stories of Vietnam and Cambodia overlap beautifully. The girls are tossed about by a torrent of history, between colonialism and capitalism/socialism, with Durian as a symbol, and have no choice but to surrender to the currents and continue to flow through the changes.

This provocative work focuses on the maintenance work of love dolls in a German prostitution district. The viewer, standing between the dolls and their maintainers, who are being consumed and idealised on a daily basis, will have a strange experience of being suspended somewhere between industrial society

The ‘Cyborg’ had no precedent in the history of Western thought[15], and being free from patriarchy and capitalist colonialism, Haraway imagined the possibility of overcoming the innate oppressiveness of gender difference through ‘Cyborgification’[16].

Artistic representations of ‘women’ and ‘machines’ have existed since before the Second World War; Exter was involved in the production of the first Soviet science fiction film, which included cyborg characters (Martians) who wear materials from Mars and seem to have acquired enormous powers. However, in the battle between cyborgs and humans, the humans ultimately win. Is there any connection with the significant feminisation of the workforce, mainly in capitalist countries, after the Second World War?

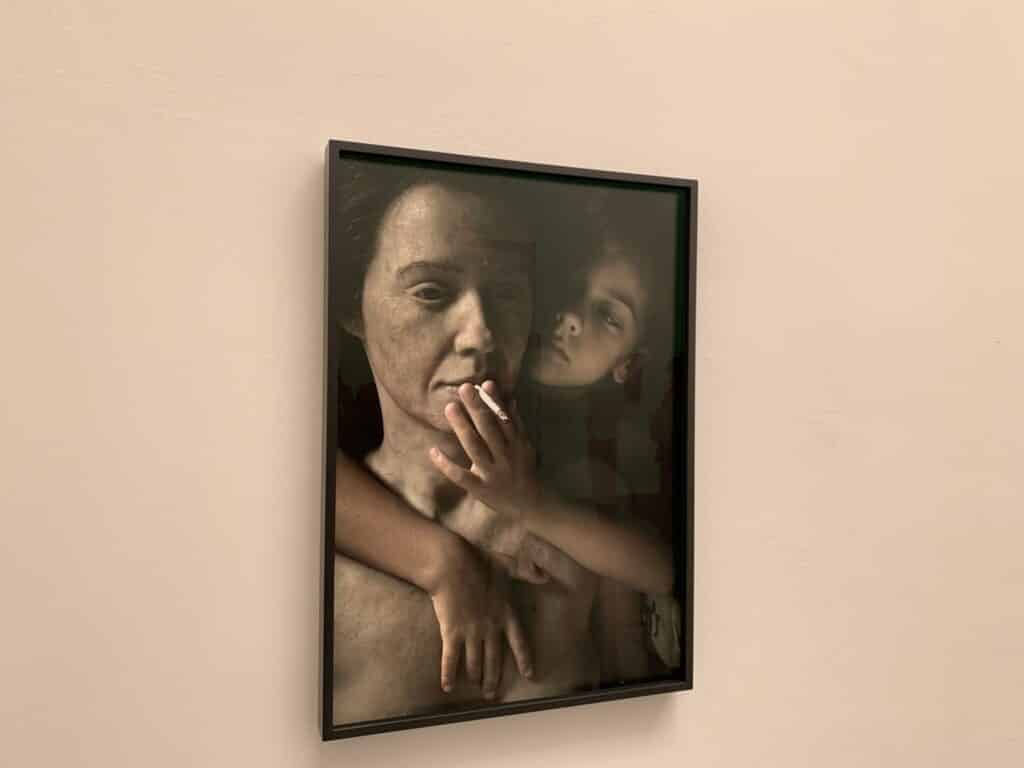

Although they appear to be portraits of a mother and child, the ‘mother’ in everyday life can be seen as a puppet (cyborg?). Was this how Aneta’s ‘mother’ was portrayed in her childhood? On the other hand, if you look closely, it appears that the daughter is actually taking care of the mother (doll). This causes us to rethink the relationship between ‘mother and child’

In addition, technological changes in labor practices, accompanied by changes in the forms of work, such as informal employment, temporary work, and the mobility of the labor market, not only affect women, but also, as a corollary, have an impact on the male proletariat and older generation of men. In other words, even for some male workers, the “feminization of the Labor Force”, which is responsible for reproduction at low wages, continues to become more common, and the Haraway’s ideas continue to become more relevant.[17]

Bricklayers in northern Sudan work in the intense heat, carrying out gruelling brick manufacturing by day and building structures by night. The end result is a huge monstrous dam, foreshadowing the apocalyptic nature of the myths surrounding mud and floods.

Haraway’s ideas are applied to not only to gender and machines, but also to parts of nature, such as plants and animals. For example, the ‘Companion Species’ that Haraway describes means relationships between species such as dogs and cats that share a life, constitute each other and shape each other’s lives[18]. In this sense, anthropocentrism, in which humans themselves are positioned independently of other beings, is surely a fallacy, and it misses the fact that humans alone cannot be taken out of the web of relationships in which we are embedded. In the Biennale, Marianna Simnett shockingly and ironically shows the boundary (tail) between humans and animals.

The story is about the ‘tail’, the boundary between human and animal, and shows the transformation of the animal-man protagonist into something other than himself. Numerous characters seemed to be searching for a ‘Partial Connection’ around the tail. The sofa in the exhibition hall was, on closer inspection, a giant tail, and I was reminded of the careless arrogance of humans sitting heavily on it.

This video work is a dynamic presentation of the process of dismantling livestock in a livestock factory that makes you want to turn away. The film, which is viewed in a special environment where the yellow light seems to have been turned on, is perhaps a wake-up call to human violence against nature. Recognising this, are we, as the title suggests, metaphorically referring to a future in which we will land on ‘Venus’, where life cannot exist?

(2) What is ‘Re-enchantment’?

Building on Haraway’s aforementioned discussion, current multispecies anthropology (ethnography) abandons the distinction between human/nature, human/machine, etc., and takes an ethnographic approach to describing human/non-human relations. It is an attempt to present and reclaim an all-encompassing genuine world of human/nonhuman intertwined events, performances, images and related beliefs in animism, shamanism, etc.[19]. In this context, the importance of art, fine art and other expressive practices is paramount.

For example, Morris Berman (1944-) termed the immersive state in the mediaeval craft world of stained glass, weaving and metalwork, as well as in ancient animistic and shamanistic expressions, ‘Participating Consciousness’. On the other hand, he refers to the engagement with the world that makes a distinction between human and nature, ‘Non-Participating Consciousness’.[20] ‘To create or express oneself immensely’ is, in other words, ‘to Participate Consciousness’ in the world, and in this sense, creating or expressing oneself immensely has the potential to become the source of a generative world that transcends Western dichotomies.

In this context, contemporary art is at the center of a movement against scientific rationalism. In other words, the Biennial’s statement shows that the restoration of mysticism, surrealism and other forms of romanticism in art history, and the reappraisal of ‘Re-enchantment’’ in contrast to Max Weber’s (1864-1920) ‘Disenchantment’ is attracting attention. In my opinion, the Western world once disenchanted art and created modern art, but the forced elimination of magical elements may have weakened the power of art in the Western world, and may have been a distant cause of art’s incorporation into industrial society. The Biennale and Documenta exhibitions, as shown in the photos below, as well as the ‘Surrealismo & Magia’ exhibition at the Peggy Guggenheim Collection near the Biennale venue [21] exhibition–featuring a number of mystical works of animism, shamanism and alchemy–demonstrate a steady revival of the enchantment element.

This fabric sculpture is influenced by nature, ancient India and crafts, and utilizes ancient Arabian sewing techniques. Woven in an immersive state, is this sculpture a garment, a genital organ, a person or a deity?

Located in the lineage of surrealist expression, Christina, with the body as its central subject, overcomes the boundaries of white/non-white, male/female and parent/child, distorting them as various entities that seem to exist in chaos pulling and pushing against each other. The writer is not the only one who was made to feel a certain three-dimensionality in spite of the two-dimensional medium of the work.

The 18th century Caribbean colony of Haiti was the richest colony in the world due to its sugar cane plantations. Tens of thousands of slaves were sent in from Africa every year and were heavily exploited. Later, the Haitian Revolution led to the establishment of a black state. The transition led to a reassessment of vernacular values. The place where the indigenous magical and cultural music expression gathered was St. Kunigundis in Kassel.

Pinaree, from Thailand, is one of the artists the writer knows well. Inspired by her own experience of breastfeeding, she has focused her expression on the female body for nearly 40 years. Using vessels, eggs, trees and other objects as breasts, her work integrates the mystique of the female body with the sacredness of Buddhist temples and other sacred sites in Asia, mystically demonstrating the possibilities of the human body.

Tatsuo Ikeda is one of the leading artists of post-war art in Japan. Trained as a kamikaze suicide pilot, from the 1960s onwards his work created a synthesis of the cosmic macrocosm and the embryonic microcosm, as represented in works such as this one. As if in response to Western dualism, which was being pushed to its limits, he was represented in the biennale, where Indian philosophy and Buddhist-influenced monism had a definite presence.

However, is the consequence of rethinking ‘Re-enchantment’ sufficient? The term ‘Re-enchantment’ does not seem to be a new one to the writer, having worked in Asia, Africa and South America for a long time, as there are naturally many magical elements in the non-Western expressions of these regions. To take a simple example, in Japan, placing ‘Mikan’ (mandarin oranges) on top of the Kagamimochi (two round piled up rice cakes) on New Year’s Day is done without any sense of discomfort. Perhaps the Mikan have a certain ‘Enchantment’ function of ‘repelling evil spirits’, and this is evident in the existence of ‘magic’ in Japanese actual life practices.

This production and expression naturally includes the cultivation of mandarin oranges. As mentioned in the past in “Mikan Myth – Thinking About the Relationship Between the Kii Peninsula and Tangerines,” Tajimanomori is worshipped at Tachibana Shrine in Wakayama Prefecture as the god of citrus fruits and confectionery. On October 10th, every year, the annual festival ‘Mikan Matsuri’ is held with great fanfare. This is not only held at the Shrine, but also at shrines in the Kinan region, where harvest festivals are held in the first half of October, in conjunction with the mandarin harvest season. There, the vernacular sites and people are the focal point for the procession (parade of portable shrines), lion dances, Mochimaki (throwing of mochi to an assembled crowd), etc., where prayers are offered in awe and gratitude to nature before the citrus fruits that have been grown are harvested. In this context, the Orange/Mikan Collective’s small exhibition from October 6-16, 2022 will hopefully provide an opportunity to take a fresh look at ‘Orange Cultivation’ as an integral part of daily life.

Nevertheless, it is probably true that such ‘Enchantment’ beliefs are weakening in Japan and in Wakayama Prefecture. What is important, perhaps, is how production and expressive practices can be integrated into life and place in order to encourage a ‘Participating Consciousness’ in the world as Berman describes. Next, in considering this practice, I would like to turn to documenta in the Part 2 of this series.

[1] Venice Biennale Website (https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022 T[2] documenta fifteen (https://documenta-fifteen.de/). Documenta

[3] The Venice Biennale website, BIENNALE ARTE2022 (https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022)

[4] Alemanni curatorial statement (https://www.labiennale.org/en/art/2022/statement-cecilia-alemani)

[5] Statement of ruangrupa (https://documenta-fifteen.de/en/about/)

[6] documenta fifteen Handbook, 2022, p. 12.

[7] One of the main members of ruangrupa . He exhibited ‘Philosopher Football Match (2011)’ at Kinan Art Week 2021. https://kinan-art.jp/en/artist/3765/

[8] Anna Tsing , translated by Jun Akamine, Misuzu Shobo, The Mushroom at the End of the World: on the possibility of Life in Capitalist Ruins, 2019, p. v

[9] Kondo, Shiaki and Mariko Yoshida (eds.), Eat, Be Eaten, Eat Each Other: Thoughts on Multispecies Ethnography, Seidosha, 2021, p. 14.

[10] Donna Haraway, translated by Sakino Takahashi, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, 2017, p. 288.

[11] Ibid, p. 348.

[12] Ibid, p. 287.

[13] ‘Feminisation of the labour force’ is a term used to describe the structural increase in female labour. For more information, see Yoshiko Hattori, The Feminisation of the Labour Force: From the Vision of Domestic Work and Household Responsibilities, https://core.ac.uk/download/pdf/35274673.pdf

[14] Donna Haraway, translated by Sakino Takahashi, Simians, Cyborgs, and Women: The Reinvention of Nature, 2017, p. 299.

[15] Ibid, p. 289.

[16] Ibid, p. 347.

[17] Ibid, pp. 321, 322.

[18] Kondo, Shiaki and Mariko Yoshida (eds.), Eat, Be Eaten, Eat Each Other: Thoughts on Multispecies Ethnography, Seidosha, 2021, pp. 14, 15.

[19] Ibid, pp. 25, 26.

[20] Morris Berman, From The Reenchantment of the World, translated by Motoyuki Shibata, Bungeishunju, 2019, pp. 430, 431.

[21] Peggy Guggenheim Collection Website (https://www.guggenheim-venice.it/)

[22] From the Wakayama Prefectural Shrine Agency website, Kitsumoto Shrine(https://wakayama-jinjacho.or.jp/jdb/sys/user/GetWjtTbl.php?JinjyaNo=2021)