Orange Collective

Communities, Hybrid-Gatherings and Orange Collectives (Part 1)-Touring the Gwangju Biennale-

Kinan Art Week Yabumoto Yuto

1 Introduction

(1) Adaptable/Resilient Fruit with Fighting Spirit

True art is a fruit that comes to fruition as a concrete reflection of a dynamic reality, a fruit that can only be harvested by a resilient responsive force that meets and confronts the challenges of a reality full of contradictions.

Declaration of Reality Doujin First Kim Chi-Ha

These are the words of Kim Chi-Ha (1941-2022), known as South Korea’s ‘poet of resistance.’ Modern and Contemporary Korean art cannot be discussed without political repression [Furukawa 2018: 2].

The ‘Gwangju People’s Uprising’ (hereafter ‘Gwangju Uprising’), the scene of a horrific massacre of civilians by military forces, was an anti-military and democratic struggle by students and citizens in Gwangju from 18 May 1980 to 27 May 1980, over the fall of the Jeonnam Provincial Government. This became the historical impetus for the democratic movement in South Korea and the creation of the ‘art of resistance’, led by Hong Sung Dam (1955-) and others (for more details, see the book, Mika Furukawa’s Korean Popular Art: Aesthetics and Ideas of Resistance).

The Gwangju Biennale Foundation, the topic of this article, has taken over the memory of its ideas and activities. The Foundation organizes the Gwangju Biennale, which is held once every two years, and continues to maintain its position as Asia’s most notable and important international exhibition. Having visited a number of museums, art spaces and galleries in Gwangju, Seoul and engaged in talking to many of the people involved in the local art field. I was surprised by the high level of interest in art and culture among the people of Gwangju and their high literacy and critical awareness. We, in Japan, could learn a lot from them, moving beyond territorial disputes, comfort women and other issues between Japan and South Korea. South Korean cultural scholar, Ogura Kizo (1959-) may be right from the perspective of culture and art when he said that ‘it is South Korea that plays a central role in the East Asian hybrid-gatherings [Ogura 2008: 12]’ (for details, see the book, ‘Japan, China and South Korea Cannot Become One’).

Now, returning to the opening words, how can our ‘orange’ be ‘fruit with resilience and adaptability? My dilemma lies in asking what type of organization our ‘Orange Collective’ should resemble as a so-called community. To start, the question should be whether the term ‘collective’ (collectivity/community) is appropriate in the first place.

Based on the historical context and practices of Kinan/Kumano, the local poet Kurata Masaki (1952-), who lives in Kumano, describes the Kumano region as a ‘repository of the soul of universal equivalence’ and he continues to search for the ultimate inclusivist and fundamental cooperativity. In order to resist ‘one absolute power or society’ like Gwangju, we need to create opportunities to question the state of the world, society, and cultivate an appreciation of Kinan/Kumano that can envision such a society. And we must also not forget that Kinan/Kumano was the last place of resistance on the eve of the birth of the communal illusion of ‘one Japan.’

(2) Art/Community/Hybrid-Gatherings

In general, a community refers to a group of people who are given some kind of ‘identity’ through a certain mode of ‘being together’ (e.g. a material foundation such as land or rivers, or a spiritual foundation such as blood, ethnicity or religion). At the Gwangju Biennale, I encountered many artworks by non-Western and indigenous artists that evoked this sense of ‘community’.

To begin with, ‘art’ is deeply related to the question of ‘community.’ According to Suga Kouko (1977-), author of The Shape of Community: Images and the Presence of People (translated from Japanese), works of art are traditionally created as ‘something to be seen’ and are recognized as ‘something common’ to be shared by many people through ‘seeing.’ In other words, as long as it presupposes that it will be seen by someone other than the creator, a work can only be established on the basis of collaboration with other people. She also states that art is like a language that transcends language, and the images of art have the function of governing the communality that connects various beings together [Suga 2017: 11].

Communities are, of course, essential for human beings to survive. However, in the modern era, ‘community’ has taken on an ethical ambiguity, as evidenced by the fact that ethnic communities, religious communities, etc, have become the cause of conflicts and war. In particular, in modernisation, human beings have become viewed as ‘individuals’ separate from the community and perceived as ‘subjects’ with rights and obligations. Under the ‘subject’ centered and ‘community’ centric ideology, separate individuals/subjects have been re-reorganized into a ‘community’ designed and managed by ‘power subjects’ [Osugi 2001: 288]. Centering on these ‘communities,’ humans have created the events of the 20th century, called the ‘century of war and revolution,’ along with various political movements such as capitalism, communism, facism, and nationalism. We who live in the 21st century continuously suffer from the after effects of the wars of that 20th century, such as global refugees and civil wars.

In order to deal with thes after effects, numerous ideological thoughts and proposals have been put forth. For example, Takaaki Yoshimoto (1924-2012), who wrote Kyodo Gensoron -The Communal Fantasy- , which explored the origins of ‘community’, urged a reconsideration and dismantling of the modern ‘community’, starting from the key concepts of an ‘Asian stage’ and an ‘African stage’. In addition, the French philosopher Jean-Luc Nancy (1940-2021), in La communauté désœuvrée -The Inoperative Community- stated that ‘community’ preceded from the formation of the concept of a ‘subject’ rather than being something that preceded the formation of the ‘subject’ [Nancy 2001: 36], and the French philosopher Maurice Blanchot points out that, surprisingly, ‘community’ is not aimed at any productive value [Blanchot 1997: 30]. Based on Nancy’s argument, Japanese anthropologist Takashi Osugi (1964-), in his main book Creoleness of Alterity, based on his fieldwork in the Republic of Trinidad and Tobago, proposed a co-existing state of ‘identity’ and ‘non-identity’ that is ‘a community that shares ‘non-identity’ [Osugi 1999:222].

Gwangju Biennale Main Hall. Photo by Yuto Yabumoto

The aforementioned Kizo Ogura, from a political science perspective, proposes the concept of a ‘共異体 Kyoitai -hybrid-gatherings-‘ which differs from a ‘共同体 Kyodotai -communities-‘ but a ‘Kyoitai -hybrid-gatherings-‘ that recognises and accepts different values to mend deep-seated conflicts and problems regarding historical perceptions not only between Japan and Korea but also for the rest of East Asia [Ogura 2008: 169-171]. In other words, if all the people or communities take ‘identicalness’ as the ultimate value in their society’, they will inevitably view those who are not ‘the same’ as causing discomfort and needing to be excluded. The Japanese Art Anthropologist, Toshiaki Ishikura (1974-) then pursues extending Ogura’s concept of ‘hybrid-gatherings’, stating that the world around humans has always been ‘more than human’, as we coexist with numerous species. Based on this, the community is also always ‘more than community’ as it is assumed to co-exist with various communities [Ishikura, Karasawa 2021: 225, 226]. With this structure in mind, how can various communities coexist as a ”hybrid-gathering’? In this article, I would like to take the expressions and images of the artists presented at the Gwangju Biennale as a starting point to grasp hints to this question.

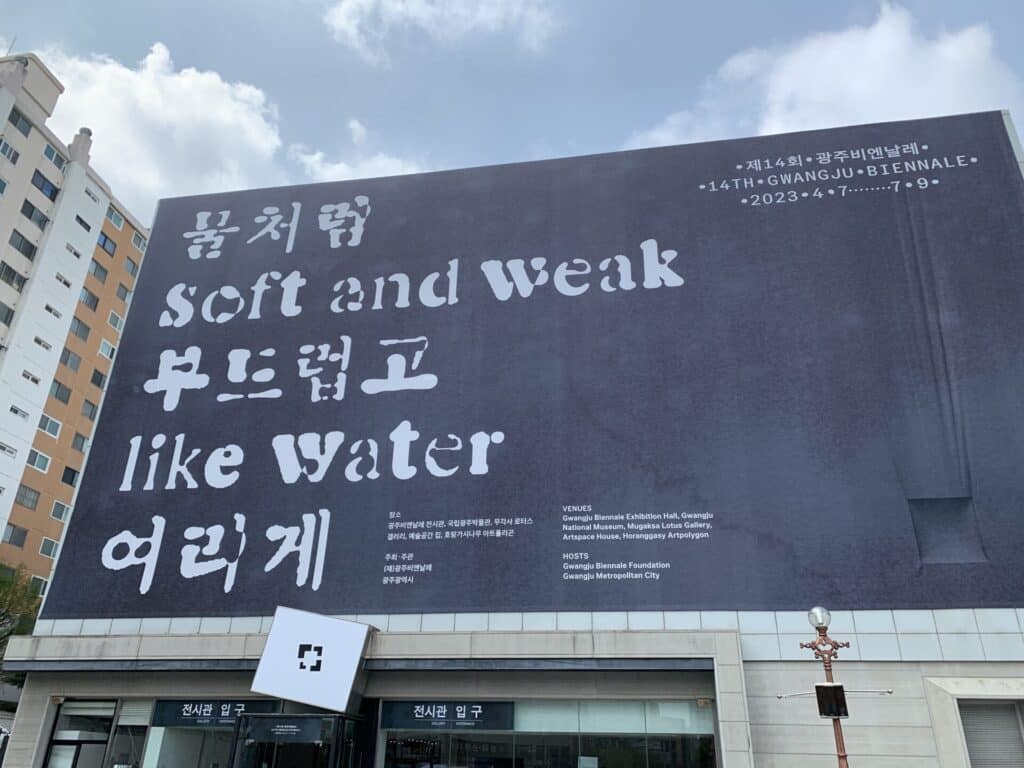

2 Concept of the 14th Gwangju Biennale

The theme of the 14th Gwangju Biennale (curated by Soo-Kyung Lee, 1969-), open from 7 April to 9 July 2023, is ‘soft and weak like water.’ This term is derived from Deo De Jing, ‘There is nothing in the world more soft and weak than water, and yet there is nothing better for attacking hard and strong things’(Dao De Jing 78). This means that water is the softest and most yielding substance yet nothing is better than water for overcoming the hard and rigid, because nothing can compete with it.

According to the exhibition’s statement, it seeks to re-imagine our shared planet as a place of symbiosis, solidarity and care by thinking through the transformative and restorative potential of ‘water’ as a metaphor, a force and a method [Gwangju Biennale official website]. Something as soft and weak as water has no immediate effect, but has the property of flowing beyond structural differences by being persistent and permeating. This contradiction and ambivalence represented by ‘water’ is similar to artists, who engage themselves with the chaos of contradictions of the world and continue to express in spite of it, as I discussed in ‘The Anthropology of Art of Mandarin Oranges and Human Beings.’ Furthermore, those artists are entrusted with lightly jumping over the ‘in betweens’ of these contradictions which define here is not so much as a place between edges, but rather a ‘place of mixing’ where diverse veins of water, from gentle currents to torrents, merge.

The aforementioned Hong is a good example of an artist living precisely ‘in between.’ Hong spent three years in prison from 1989 on suspicion of espionage under the National Security Law, where he was subjected to severe water torture. Following this experience, Hong has produced a number of water-related works, such as Bathtub – Mother, I Can See the Blue Sky of My Homeland (1996) and 20 Days in the Water (1999) [Furukawa 2018: 210-217]. These works convery different perspectives on water, such as the ‘water of life’ of the hometown where Hong was raised, whereas the ‘water of death,’ as a torture instrument, is seen as something situated in time, space and the ‘in-between’ of life and death, and is deeply connected to a vision of symbiosis and coexistence.

In light of recent trends the art world such as ‘de-anthropocentrism,’ the ‘Global South’ and ‘post-colonialism,’ as discussed in ‘The Current Coordinates of the Mikan Collective: Venice Biennale and Documenta,’ the main venue of this exhibition, the Gwangju Biennale Exhibition Hall (hereafter referred to as the ‘Main Hall’), featured a series of themes including (1) Encounter, (2) Luminous Halo, (3) Ancestral Voices, (4) Transient Sovereignty, (5) Planetary Times. The exhibitions displayed a concept, sub-themes and artworks, and in a sense, its straightforward structure made it easy to view the exhibits. While this is certainly a desirable method from the viewer’s point of understanding of the works, at the same time, my desire was to intuit expressions and images that possibly transcended these frameworks.

The following section is divided into a first part, a second part and a final part, focusing on works that moved me, and transcended these formal structures.

(Note that (1) the theme ‘Encounters,’ which was located at both the entrance and exit of the main exhibition hall, will be described in a later part of this article. Furthermore, I did not go through (5) the theme ‘Planetary Times’ regarding ecosystem conservation, because the description inevitably came from the perspective of a ‘global community’ concept which I would rather not write about here. (However, this is probably an area in which the curators of this exhibition excel, and the exhibition will be discussed by many experts, so I will try again in the future, referring to them).

3 Who Are the ‘Others’?

First, I will discuss the theme ‘Luminous Halo’, which means halo. Is it an image of finding ‘light’ in the pitch-dark world between life and death, as in Hong’s work.

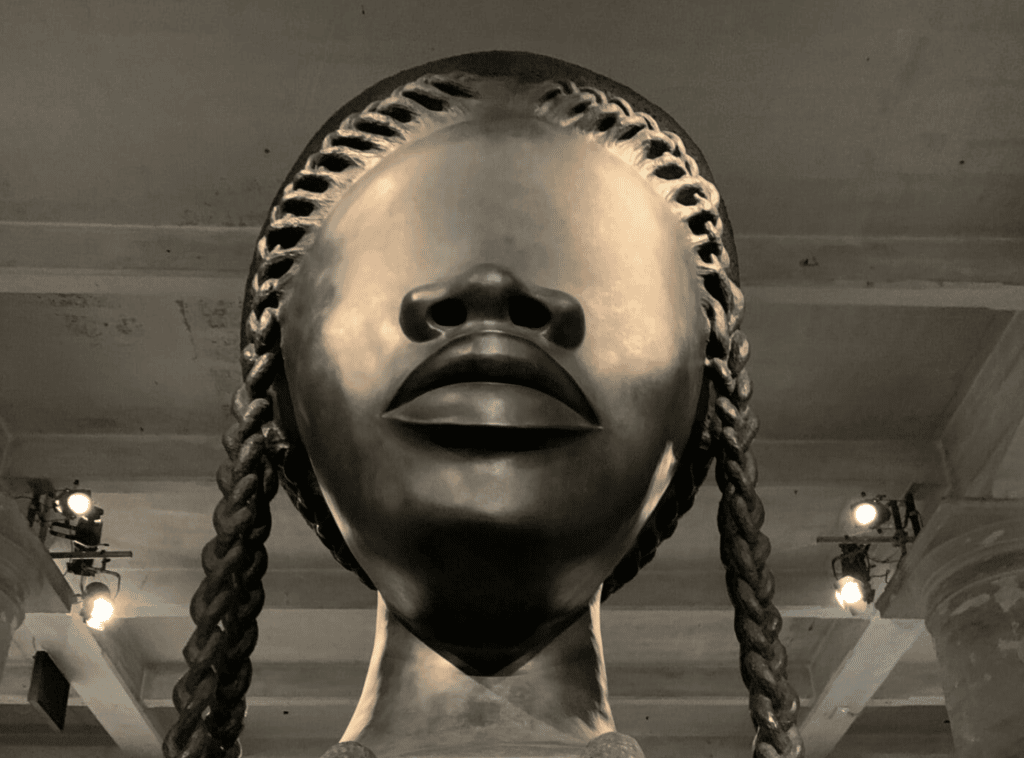

The statement describes a commitment to seeing the ‘light’ of Gwangju as a halo, and to continue to seek ‘justice’ in the spirit of the Gwangju Incident, transcending time and place, like an indelible light. The halo reminds me of the ‘face’ of Buddha in Buddhism, Christ or the Virgin in Christianity, which appears with the halo. The face is the place where the deepest vulnerability of an organism is exposed, and where its characteristics and personality emerge. The very ‘face’ is deeply associated with open ‘andersheit’ and ‘fremdheit’.

Emmanuel Levinas (1906-1995) is an indispensable philosopher when thinking about ‘light’ and the ‘existence of otherness.’ Levinas was a prisoner of war in concentration camps for multiple years during World War II and lost his family he had left behind in Lithuania in the Holocaust. He states that:

We call the manner in which the ‘Other’ appears to me, overflowing the idea of the ‘other’ in me, a face. This way, it does not appear as a subject under my gaze, nor is it displayed as a totality of qualities that form an image. (omitted) The face of the Other appears in itself, not through the qualities it possesses. The face of the Other expresses itself [Levinas 2020: 72].

In a nutshell, is the other the truth?

Levinas’s language is always difficult to understand. He states that the ‘phenomenon of the appearance of the other in the self’ is the ‘face’. In other words, the other transcends all limitations, manifests itself to the self, encounters and comes into contact with the faces, and creates a field of sociality and communality between the self and the other. According to Levinas, the ‘other’ is an infinite being, always deviating from the self and impossible to fully understand. In this sense, only the ‘face’ can prompt us to reflect, and by meeting and welcoming the other, we can foster moral consciousness and justice [Levinas 2020:101, 120, 175].

The Italian philosopher Giorgio Agamben (1942-) also argued that ‘face is an irreparable exposure of human beings’ and that ‘face is the only place of communality’ [Agamben 2020: 95-96].

In the Luminous Halo, the ‘faces’ of unknown female students were randomly displayed in Soun-Gui Kim’s (1946 -)’s Poems (2023.) Another face-related artwork was Elephant without Trunk (2023) by Oum Jeongsoon (1961-), which featured an elephant-like creature with only its ‘face/head’ missing– in light of Agamben’s statement, what are these artworks, one prominently featuring faces and the other without faces, telling us?

Left: Faces of female students displayed in Song’s Poems (2023)

If the ‘face’ is thus the only place of communality, then contemporary artworks in which the ‘face’ is displayed can be said to constantly pose questions about the nature of people’s communality. By way of contrast, a new work on the same exhibition floor, The Spirit Level (2023), by Thai artist Taiki Sakpisit (1975-), emitted a dubious ‘light’ in order to focus the viewer’s attention on the ‘faces.’

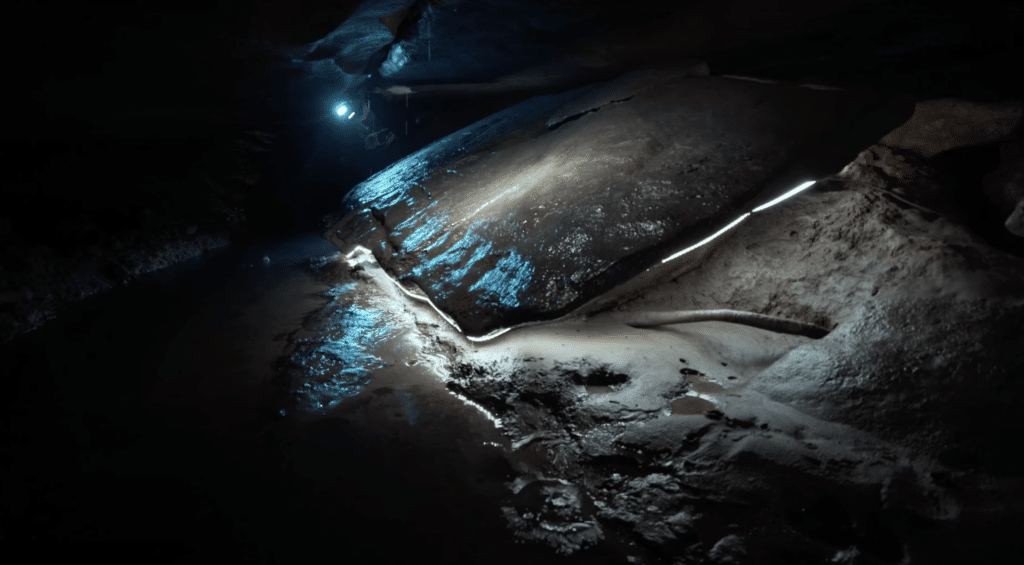

The Spirit Level (2023)

Left: Water flow of the Mekong River. Right: Underground caves of the Mekong River. Photo by Yuto Yabumoto

The film begins in the Isaan region along the Mekong River in north-eastern Thailand, where the viewer wanders along the river into an underground cave where the Naga of the Underworld is worshiped. The film has suggestive images showing the ‘faces’ of sculpted horses, elephants and fish on a mural, in addition to real horses and dogs. While viewing this, I wondered if the people living along the Mekong River have regarded non-human beings as ‘others’ since ancient times.

In the video, the Thai people in the traditional costumes of the Kingdom of Thailand in an upside-down composition suddenly enter the shoot in reverse rotation. The faces of people who worship the Kingdom of Thailand are shown upside down. This can be seen as the artist’s resistance or skepticism towards the Thai monarchy. It seems to throw cold water on Levinas’s concept of the ‘other.’ In Thailand today, conflicting communities, with different relationships to the monarchy, are stuck being unable to communicate with each other. This being the case, I surmise that there seems to exist two incompatible communities in Thai.

The Spirit Level (2023)

Thai people reflected upside down. Photo by Yuto Yabumoto

Then, after the images return to normal, the film shows the scenery of the Mekong River. Later, an abandoned animistic shrine and an old shaman appear, with images of animals, fish and insects here and there. Does Taiki perhaps see a potential solution for the conflict in animism and spirit beliefs? In this scene, an old woman’s face is exposed along with a yellow flower called Golden Shower, the national flower of Thailand, and is shown as a high-speed dissolve multiple exposure (the front screen is projected onto the back screen, the back screen fades and eventually changes to the front screen), with dynamic sound and images are projected as if they were a flip-book. In this image, combined with the dissolve effect, the old Thai woman appears as if she is a multiple being, as if she is living more than one life. Indeed, the ‘faces’ displayed here are ‘identical’ but also ‘non-identical’ multiple ‘faces’ existing at different times. Furthermore, although they are invisible, it seems that multiple ‘spirits’ also appear in those multiple times.

Then comes a sudden silence. The old woman’s image is stopped for so long that people might easily mistake it for a malfunction in the projector. However, the opposite is true. So, then, why does Taiki purposely ‘disconnect’ his artwork and time by pausing the image for a long time? Although modern animism theory often focuses on the fluid connections between various beings, I feel that the ‘disconnection’ of relations is actually the energy generating connections. Is it because Levinas assumes this energy for generating connections is needed, that he absolutely divides the ‘self’ and the ‘other’? In other words, perhaps absolute ‘otherness’ is the source of orientation towards the ‘other.’

The mixed images in these films are extremely chaotic, with human/non-human, visible/invisible, body/spirit, time and energy in flux/disconnection. However, it might be possible to call the state in which these beings and states ‘exist together’ as ‘hybrid-gatherings.’

As background, the Kingdom of Thailand has a complex history in which the indigenous Thai animism of ‘spirit belief’ (Phi or Ban Phi) has not only been marginalized, but has also had its history and stories pushed away to the periphery, altered, or erased in the process of the centralisation of power and the nationalization of Buddhism. Instead of ‘restoring’ it, by recapturing the ‘something’ or the ‘image’ that comes to the surface, like the image Taiki creates, Taiki may be attempting to communicate with ‘others’ of multiple species and dimensions.

The film’s images are also, as mentioned above, time stopped, fast-forwarded and reversed. Why does Taiki attempt to dismantle our sense of time through multiple exposures? I think Levinas’s words have an answer to this question:

Memory reclaims, inverts and suspends what has already been accomplished, which is contained – naturally – in birth. (omitted). Through memory, I ground myself retroactively in the past after the fact. At the absolute past of origin, I do not have a subject to accept, and therefore I take on what has been destined for me. Memory takes on the passivity of the past a posteriori and controls the past [Levinas 2020: 86].

As the saying goes, we are creating the past from the future.

It seems that Levinas could not, by any means, tolerate the ‘historical inevitability’ of the murder of his family members by the Holocaust. Furthermore, French philosopher Didi Huberman (1953-) has similarly stated that ‘no matter how new the timeless images are, if we are confronted with those images, at the same time, the past is reconstructed’ [Huberman 2012: 4]. It is as if we have made ‘the past’ out of images of the present and the future, through our unconscious creation. If so, does this mean that we may be able to recreate the ‘past’ through the power of images?

Levinas then also states that ‘sociality is more than the source of the representations we have about time, it is time itself’ [Levinas 1996:195]. In other words, he is not saying that ‘time itself creates dialogue’, but that ‘time is produced through dialogue with others.’ Through images, Taiki may be exploring the possibility of encouraging an open dialogue with the Other and reconstructing the past, present and future in a different form to the act of struggle in contemporary Thailand.

In the second half of The Spirit Level (2023), a cow slaughterhouse suddenly appears. In the film, the image of ‘something’ being returned to the soil and salt is shown at the cowhouse where many cows are thought to have existed and been killed before and after. Traces of the ‘other’ in which the ‘something’ existed can be seen from the site. This is connected to Levinas’s core concept of ‘il y a’ French for ‘there is something’ or ‘there is someone.’ The overlap between Levinas’s ‘il y a’ concept and the presence of the slaughtered cow in the film is shown by the following words?

Let us imagine that every being, thing and person has returned to nothingness. This return to nothingness cannot be placed outside of all events, but what about this nothingness itself, even if it is only a night of nothingness or silence, something is happening. We write down this impersonal, nameless, but unquenchable presence, this ‘burnout’, this burnout that is buzzing in the depths of nothingness, with the word ‘is’. <’Being’ is ‘being in general’ in that it refuses to take a personal form [Levinas 2005: 114].

Based on this, does it mean that ‘existence will not disappear,’ as with the cowhouse?

’Il y a’ refers to the state of being when beings, such as people and things, are swallowed up by the darkness of night, losing their individual distinctions, each having no consciousness, no subjectivity, and returning to ‘nothingness.’ Levinas sees the function of art as exposing the existence of ‘il y a,’ generally, and ‘to offer the image of the object instead of the object itself’ [Levinas 2005: 112]. He then emphasizes that art transforms things into images rather than concepts. When something becomes an ‘image,’ it becomes a ‘non-object’ and the image escapes our understanding [Suga 2017: 115]. Through this, the image of art is a foreign object that brings about the feature of ‘otherness.’ The image of ‘other’ may be the source of the overwhelming energy caused by imaging of ‘the other.’

According to Taiki, the disturbing depictions within the video are inspired by the images of three anti-government activists whose bodies were found in the Mekong River in 2018. The anti-government activists were said to have been mutilated, had their guts stuffed with stones and drowned at the bottom of the Mekong River. Thailand is said to have experienced a series of disappearances and assassinations of political dissidents since the 1970s. Just like the Nazi extermination camps, their fate is ‘unrepresentable’ and ‘inconceivable.’ However, the exposure of the image of slaughter that Taiki creates transcends the species of humanity and cows, and as an image of ‘otherness,’ ‘something’ looms over us like an obsession.

However, my feeling is that the ‘face’ of the monotheistic God is always clinging to Levinas’s words. As Taiki has titled his work 《The Spirit Level 》, he may be attempting to transcend Levinas’s limitations by horizontally rethinking the ‘face’ of the ‘one God’, the non-human ‘soul’ or ‘神 -Kami-.’

Taiki’s video and audio are disturbing and dark. The situation surrounding the Thai community may still be pitch-dark. However, the ‘light’ projected from the projector is constantly being projected, and furthermore, a sensor-type light installed under the projector illuminates the viewer from behind, as if to reveal a ‘halo’. When I was exposed to the light projected from behind the projector, I was reminded of Japanese anthropologist Keiji Iwata (1922-2013), whose main field was Southeast Asia and who was a member of the Kyoto School of Anthropology.

Iwata states that ‘Every being has a spirit. It is a thing and a Kami at the same time [Iwata 2020: 12].’ As he states, we are both the beings who see the ‘faces’ that are exposed and the beings who can see our ‘faces.’ Levinas completely separates the ‘self’ from the ‘other’, but the experience that Taiki brought to me was exactly like standing at the crossroads between the ‘self’ and the ‘other.’

The system is lit from behind with a variety of lights. Courtesy of the artist.

Iwata states that ‘Needless to say, the religion called animism has no doctrine, no cult and no religious professions. Therefore, it is originally a religion of each and every person [Iwata 2020: 19].’ The very idea that all beings are ‘カミ -kami-‘ (Iwata used the word ‘カミ -kami-,’ instead of ‘神 -kami- ‘), could means that a ‘halo’ shines on all beings, if applied to Taiki’s film. In considering animism and community, there are no norms in animism such as the ‘Thai Royal Code’, nor are there large communities that seek ‘sameness’ such as the ‘animist cult.’ In considering ‘community/hybrid-gatherings’, it may be necessary to return to these root ideas.

In the next section, the second theme of the exhibition, Ancestral Voices, is discussed in relation to this question. The ‘animistic’ expressions of the indigenous artists exhibited on the same floor, and their images of ‘communality’, will be discussed in the next part.

(Ru k’ ox k’ob’el jun ojer etemab’el) 2023 by Edgar Calel. Yuto Yabumoto

<References>

- Ishikura, Toshiaki and Taisuke Karasawa. “The Anthropology of Our External Organs and the Concept of Co-heterogeneity,’ More Than Human: Multispecies Anthropology and Environmental Humanities, Ibunsha, 2021.

- Iwata, Keiji. “The Age of Animism,” Hozokan, 2020 [Translated from Japanese].

- Levinas,Emmanuel. “Totality and Infinity,” Translated by Toshihiro Fujioka, Kodansha Academic Library, 2020.

- Levinas, Emmanuel. “Existence to the Existents,” Translated by Osamu Nishitani, Kodansha, 1996.

- Osugi, Takashi. The Creole of Inaction, Iwanami Shoten, 1999. [Translated from Japanese].

- Osugi,Takashi. “To/In Community through Non-identity,” Edited by Sugishima, Keishi, Reconstructing Anthropological Practice: After the Postcolonial Turn, Sekaishisosha, 2001. [Translated from Japanese].

- Ogura, Kizo. “ Japan, China and Korea Cannot Become One,” Kadokawa Shoten, 2008. [Translated from Japanese].

- Suga,Kouko. “The Shape of Community: On Images and People’s Existence,” Kodansha, 2017. [Translated from Japanese].

- Agamben,Giorgio. “Beyond Human Rights – Notes on Political Philosophy,” Translated by Takakuwa,Kazumi. Eibunsha, 2000.

- Hubermann,Georges Didi. “In Front of Time: Art History and the Anachronism of Images,” Translated by Ono,Yasuo and Mikoda,Yoshihisa. Hosei University Press, 2012.

- Jean-Luc, Nancy. “The Community of Inaction: Thinking about Sharing to Question Philosophy,” Translated by Nishitani,Osamu and Yasuhara, Shin-ichiro Ibunsha, 2001.

- Furukawa, Mika. “Korean Popular Art: Aesthetics and Ideas of Resistance,” Iwanami Shoten, 2018. [Translated from Japanese].

- Maurice Blanchot. “The Unveiled Community,” Translated by Nishitani,Osamu. Chikuma Shobo, 1997.

- Gwangju Biennale Official Website, viewed May 2023 (https://14gwangjubiennale.com/#aboutAnchor)