Orange Collective

Communities, Hybrid-Gatherings and Orange Collective (Part 2)-Touring the Gwangju Biennale –

Kinan Art Week, Yuto Yabumoto

4 Indigenous Thought and Hybrid-Gatherings

Following the first part, focusing on one of the exhibition themes, “Who is the Other,” I would like to discuss the third theme of the main venue, “Ancestral Voices,” in this article. The statement can be summarized as inheriting Gwangju’s historical identity, listening to indigenous voices around the world, and reinterpreting local traditions and introducing communal practices rooted locally. Additionally, it confronts western modernity and evokes the imagination of alternative “intelligence.”

(1) Ainu/Ancestor = Me?

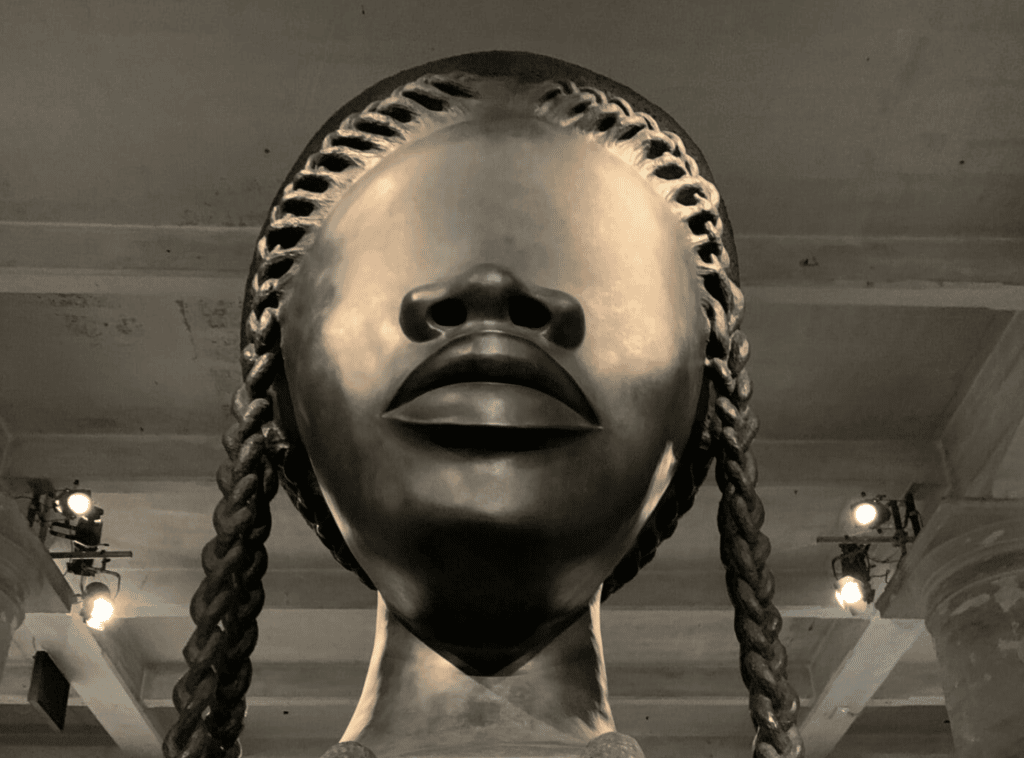

Mayunkiki (1982-), an artist and musician with roots in the Ainu of Hokkaido confronted this theme. As we walked on the same floor, her ‘face’ jumped out at us.

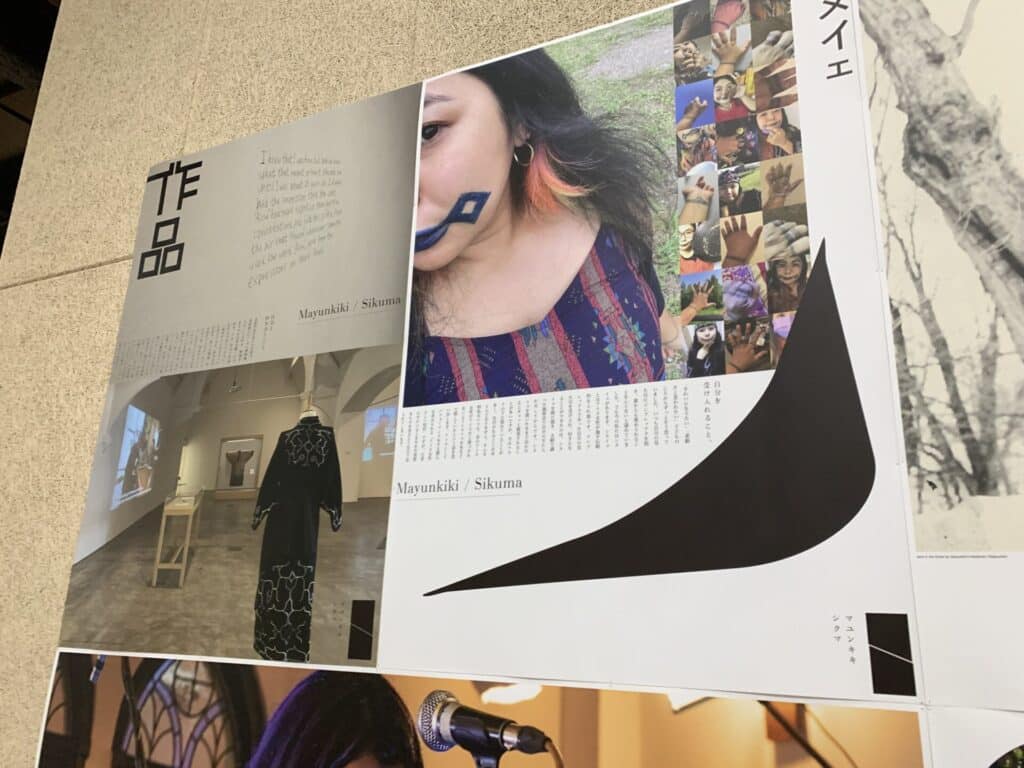

The moment I saw the Mayunkiki poster, I finally felt relief. This is because, looking around the main venue, the whole place is full of huge, luxurious installations and artworks. In other words, there is a strong element of spectacle (manipulating collective perception and transforming it into a single commodity after monopolizing memory and communication [Agamben 2012:100]), which Giorgio Agamben uses in an ambivalent sense in The Coming Community. As many of the works originate from small stories of individuals and peoples, I honestly could not sympathize with their bloated presentations. In this sense, I even felt a certain ‘resistance’ to the exhibition from Mayunkiki’s posters, which were unframed, unadorned and simply placed against other posh works.

Compared to some of the extravagant works, some viewers may have thought “What is this?”, while others may have wondered “Has the artist lost her motivation?” Some viewers may have misinterpreted this as “unmotivated” or “just too simple.” However, this perception, at least for me, was quite the opposite. I was most moved by the carefully calculated, yet unadorned, life-size exhibition of artworks.

Mayunkiki’s work, Sikuma 2023, is a series of posters that present her personal and traditional Ainu imagery while adding text. According to the caption, ‘Sikuma’ means ‘boundary’ in Ainu.

Where does the ‘space’ between ‘Japanese’ and ‘Ainu’ begin and end? In the two images that coexist in the above photograph, the ‘faces’ of the ‘self/Mayunkiki’ and the ‘other/ancestor’ are blended together.

The text pasted at the end of the Mayunkiki’s exhibition is an important text, as it was translated into Korean and English, and I would like to quote it here.

On a daily basis, I have always felt that there is a big discrepancy between the ‘me as Ainu’ in other people’s images and the actual me. I feel that there are many one-sided assumptions and ideals imposed on the Ainu, who are the indigenous people of the northern part of the Japanese archipelago, especially Hokkaido, and who are currently attracting attention at home and abroad, and that I sometimes overreact due to resistance or aversion to them, or conversely, without even knowing it myself, I try to conform to their image. In some cases, we try to conform to these images without even realizing it. Where are the boundaries between the perspectives of others and our own? Perhaps there is no such thing.

In this work, in the process of verbalizing the gap I feel, even a little, that I may be able to notice the boundaries that I have created unconsciously.

Mayunkiki has also expressed her feelings in other media, saying that “it is often hard to live as Ainu [Hachiya 2023:55],” and that she is troubled by the denial of Ainu existence, the stereotyped image of the Ainu, and excessive expectations of them. I think it was the Gwangju Biennale that gave rise to these excessive expectations. As Mayunkiki described as the ‘rehabilitation of the Ainu [Hachiya 2023:55],’ the Biennale exhibition could also be considered part of the ‘rehabilitation’ (becoming fit again) through cultural activities such as language, food, music and decoration to showcase the real Mayunkiki.

(*For more information on the issue of stereotyped representations of ‘Ainu’ and ‘Art’, the consumption of its image and its continued transmission, see Shinobu Ikeda (ed.), ‘Questioning Ainu Art‘).

The question of Mayunkiki’s ‘identity’ is, as I mentioned in the first part, related to “between,” the theme of this exhibition, ‘water’ and the place where those questions are intermingled. Japanese Anthropologist Toshiaki Ishikura (1976-) states that the “hybrid-gatherings” is a heterotopian reality that presupposes the coexistence of different values and time frames, and that the “art” that opens from this dimension is produced from the uncertainty of modern life that lies between science and myth [Ishikura 2020:51]. In this sense, Mayunkiki’s “images” and “artworks” are created in coexistence with the past and present of the Ainu, transcending time and intertwining with different values and times periods, while asking questions about her identity and the uncertainty of her life.

In surveying Mayunkiki’s previous exhibitions (e.g. SINRIT at the CAI Institute of Contemporary Art, Sapporo, and NIRIN at the Sydney Biennale), I assumed that her art was based on ‘animism’ and ‘gift’ ideology.

(*Although ‘Animism’ seems to conflict with Mayunkiki’s ‘NG words’, as seen in videos such as ‘Don’t say it! NG word collection volume‘.)

For instance, Mayunkiki practices drawing her own Sinuye (traditional tattoos applied by Ainu women) on their own ‘faces’ by themselves. However, in everyday life they hide it under their masks. Yet, when they have an opportunity to perform as Ainu, they expose them in a big way.

This could be described as a fluid back-and-forth activity between ‘self’ and ‘other’ that is characteristic of animism. Japanese anthropologist Keiji Iwata, whom I mentioned in the first part, sees “everything as Kami -God-“. In other words, conscious encounters with all the ‘Kami’ (others, everything surrounding you) that envelop the self, and the perception that these ‘kami’ (others) are also the elements that make up the self and also what surrounds the outside. Iwata may have called it ‘animism’ from an anthropological perspective. In this way, the ‘life’ of all beings is always open to the outside, and the self never appears alone, but rather emerges through contact with others. And vice versa, the other manifests itself by touching the self.

As Mayunkiki says, “The reason why I have been able to live through hard and painful days without giving up is because there were many words from the people who spoke to me. Their faces come to mind when I think of those difficult days” [Hachiya 2023:55]”. I think we exist only when other people exist. In this sense, we are all dependent on others.

As mentioned above, Mayunkiki’s practice is itself an act of continuing dialogue with the ‘other’ – her family/ancestors and local residents. She sublimates this process into art forms such as posters, interviews and performances, which she ‘gifts’ to others. In this regard, Marcel Mauss (1872-1950), author of The Gift, states that ‘gift-giving’ is ‘one of the bases of human existence [Mauss 2014: 63]’ and is ‘giving something of oneself [Mauss 2014: 99]’. In other words, the recipient of the gift receives not only the object but also “something” from the giver that is mixed with the object. As Mauss states, it is “a soul-breathed thing as itself [Mauss 2014:307]”, thus, ‘gift-giving’ and ‘animism’ are deeply connected. Indeed, Morse researcher Takumi Moriyama (1961-) states that Mauss himself was an animist [Moriyama 2022:254]’.

Yet, for the givers who have given away ‘something of themself’, there is a ‘residue’ of something left even after the ‘something’ is handed over. Moriyama defines this ‘residue’ as ‘an unalienable thing (something that cannot be given away and must not be transferred)’ [Moriyama 2021:282]. In the ‘space’ between the ‘self’ and the ‘other’, or the ‘shikuma’ (boundary) as Mayunkiki calls it, there is surely an absolute wall, as Levinas described in the first part.

However, Mayunkiki slowly permeates this boundary between herself and others like ‘water’ through her artistic practice, including dialogue and interviews, without giving up herself or without destroying her identity, yet at the same time detaching herself in order to freely move between herself and out of the other. Mayunkiki works, in which she animistically moves ‘between’ the self and the other freely, while always ‘owning herself and the other – and giving’, is the gift Mauss mentioned. Also, needless to say, there is always a “communality” with the other. Furthermore, here we can also find the key to how “hybrid-gathering” should exist.

There is no end to the back-and-forth work between the self’ and the other. The Italian philosopher Robert Esposito (1950-) analyzes the etymology of the Latin words ‘communitas’ and its antonym ‘immunitas’. He focuses on the core of those words ‘munus’, which means ‘burden, service, gift’. Among them, he particularly focuses on the word “gift,” in doing so, deepening its concept and root meaning. In examining etymology, Esposito says that ‘birth’ itself is a ‘gift’ for existence, and that the obligations that arise from receiving that ‘life’ can not be avoided [Kan 2017:176, 177]. In Espositi’s following words, he concludes that this unfinished or incomplete state, that can never be filled because of lack, is what characterizes community.

Community is both necessary and impossible. Communities do not simply arise due to a lack. Nor is it simply that it will never be completed. Rather, community lacks itself, in the special sense that what sustains us together and forms us as common-being, together-being, is precisely lack, imperfection, and debt. [Esposito 2012:42].

In other words, ‘lack is what brings people together’.

The ‘community’ that emerges through the art of Mayunkiki cannot stand alone as a ‘self’ or ‘subject’ on its own. In other words, the members of the community are not the same as the self, as it is a community consisting of the ‘self’ and an ‘other’. In this concept of an incomplete community based on lack, there may be a hint to revealing what contains the “displacement” of Mayunkiki.

Finally, what was curious was that the text on Mayunkiki’s poster was only written in the Japanese language (with the exception of the last quotation). Looking at the poster as it is, I am reminded of Blanchot’s The Unrevealable Community. Blanchot states that “the undisclosed community never reveals its reality [Blanchot 1997: 116]”. Surprisingly, he states that only communication, which has excluded mutual understanding of thoughts through words, and the harmony of feelings, will survive in the future. The ‘something’ expressed in the ‘act of saying’, the ‘act of writing’ and the ‘act of throwing oneself out’, which are in a state of ‘inaction’ in the sense that they have meaningless and ineffectual qualities, while communality is found in contact with that ‘something’. Blanchot called it ‘a community of people without a community’–an undisclosed community.

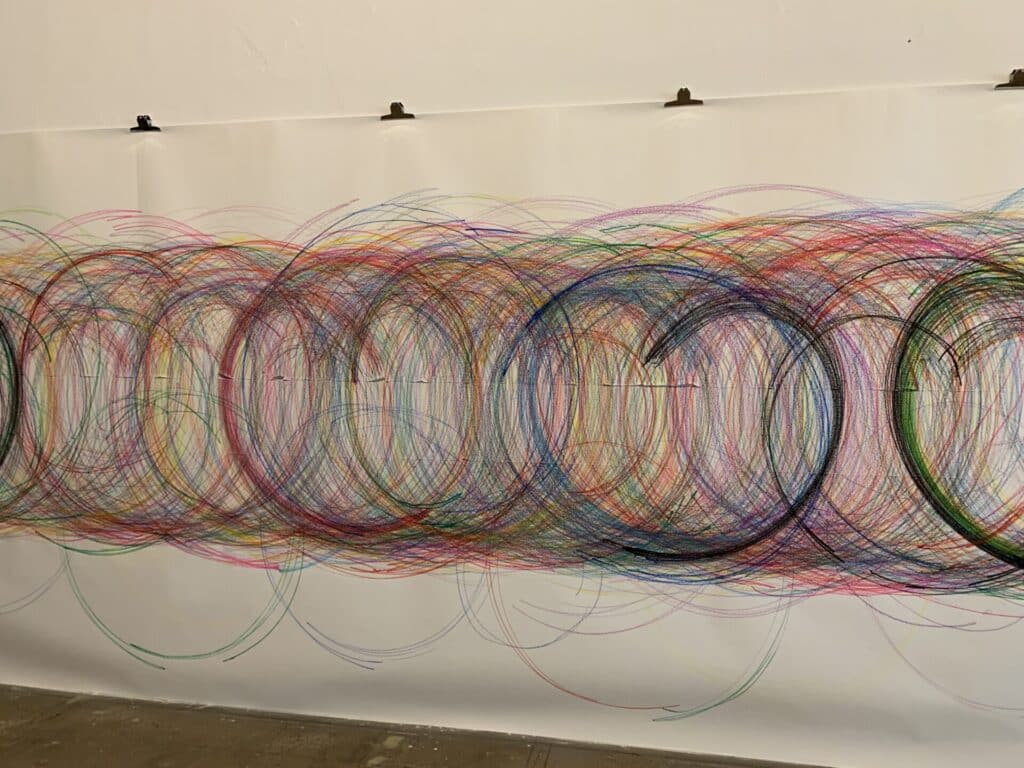

Photo (left) 2-1 ‘Lee Kun Yong’s Bodyscape 76-3 (1967) Spirals drawn by unknown people’, photo by Yuto Yabumoto.

Photo (right) 2-2 ‘Music played automatically by Tarek Atoui’s The Elemental Set (2021) programme’, photo by Yuto Yabumoto.

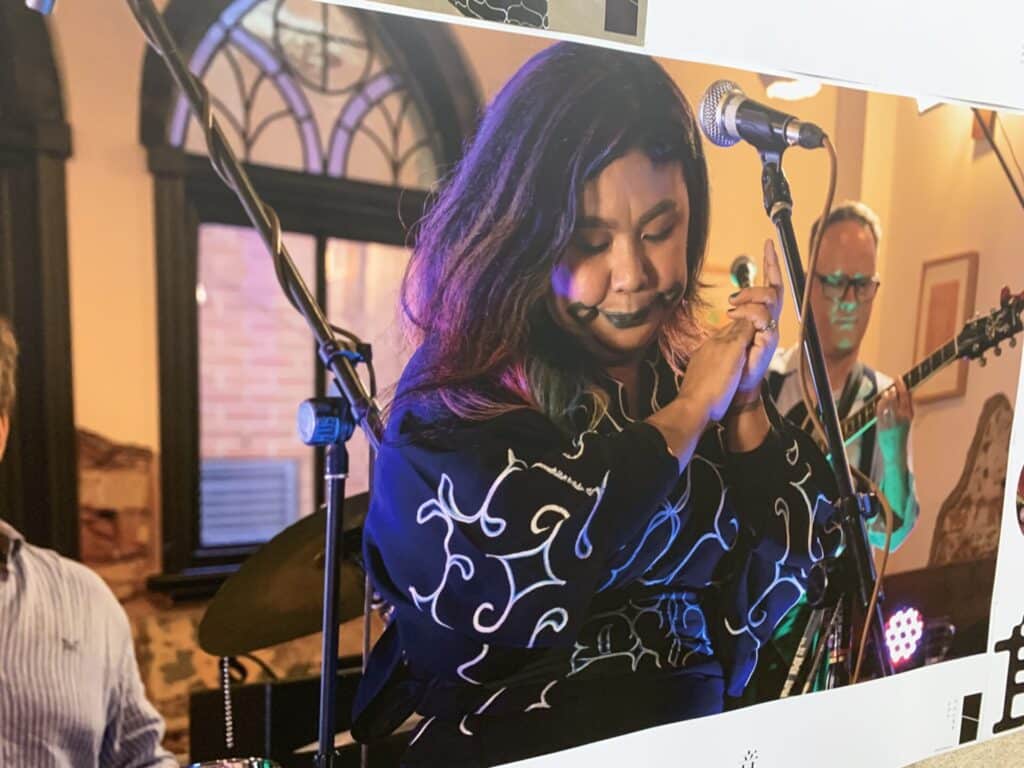

As shown in the photo above, on the same floor, the ‘the act of just writing’ and the the ‘act of just making sounds’ are exposed. Compared to these, I think that Mayunkiki’s texts seem to creates an open communality with that ‘something’ Mayunkiki’s ‘performance’ at the Gwangju Biennale on 17 June gave us a glimpse of what Agamben calls ‘undisclosed communality’. This ‘act of throwing oneself out’ will become what Mayunkiki calls ‘proof that the Ainu are alive [Hachiya 2023:55]’.

(2) Indigenous Peoples Living in Sabah and the Co-epiral

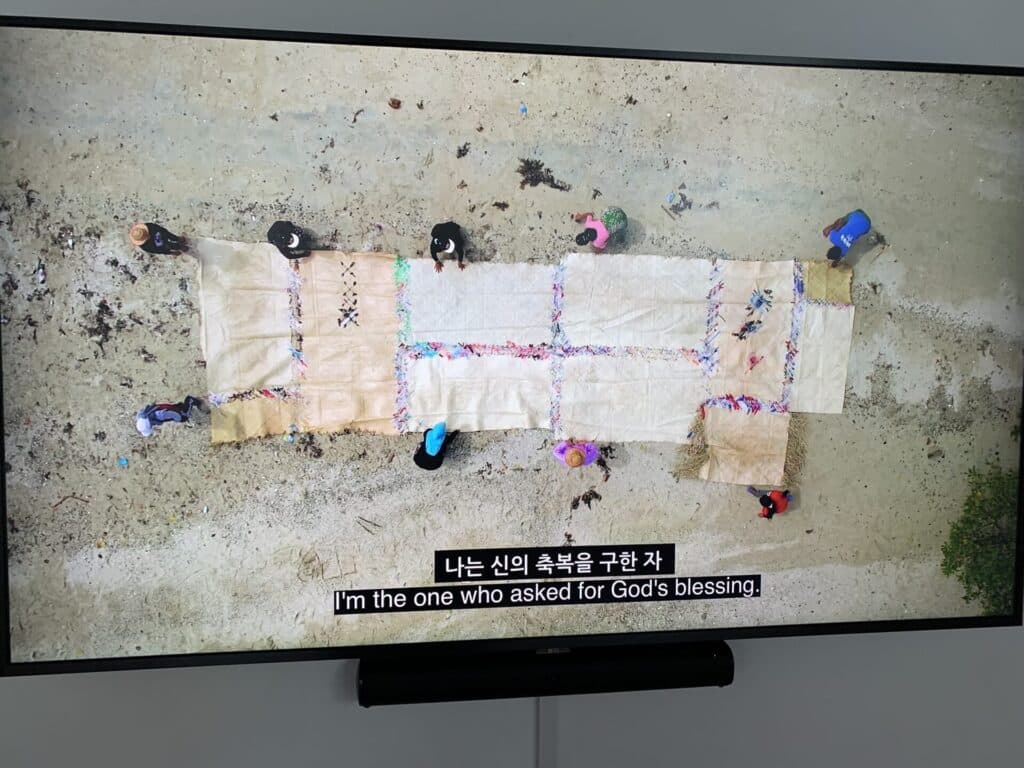

An installation and video work by I-Lann Yee (1971-) dealing with the geopolitically turbulent history of island Southeast Asia was installed on the border between the first and second floors of the ‘Luminous Halo’ and ‘Voices of the Ancestors’ floors.

Yee was born in Konakitabalu, Malaysia, to a mother from New Zealand and a father from Kadazan, an indigenous people of Sabah. His film Budil’s Song, 2023, features a conversation between indigenous people living in Sabah, north-east of Malaysian Borneo. The production process, which included migration along the coast of Omadal Island on the border between the Sulu Sea and the Celebes Sea, on the Omadal island, was disclosed.

Since independence from the British, Sabah has never ceased to be a part of border disputes between Indonesia and the Philippines. Since pre-colonial times, they have lived in a vast area that straddles the current borders [Nagatsu 2019:2]. It is no exaggeration to say that the history of Sabah is a history of migration/refugees and border crossing. In addition to pre-colonial migrations, the indigenous people of Sabah have lived alongside numerous immigrant populations, including the influx of foreign workers under British policy during the colonial period, Muslim refugees from the southern Philippines in the 1970s, and the constant flow of migrant workers since the 1950s [Uesugi 2002: 118]. In addition, the country faces numerous problems, including identity issues between Malay, Chinese, immigrants and indigenous peoples and mixed races. Furthermore, there are religious conflicts regarding Islam among indigenous peoples and the prohibition of religious rituals that deviate from Islam.

(*This background is detailed in ‘Living the Border: A Dynamic Ethnography of Sabah, Kaisama, Malaysia‘ by cultural anthropologist Kazufumi Nagatsu (1968-).)

Yee works with the indigenous communities of Sabah, including the sea-living Sea Sama (Bajau), land-living Land Sama and Kadazan (Dusun) tribes, and collaborates with the artists who live there to pass on ancestral traditions and ponder how the open communities should exist. The installation Tepo Putih Ikan Masin (White Mat for Salted Fish) 2023 was created by sewing and splicing together mats used at home for drying fish and other household chores, with plastic waste flotsam collected from the beaches of the islands.

The production of mats takes place in parallel with movement and conversation’, photo by Yuto Yabumoto

The footage shows that there are mainly indigenous people living along the coast, though also people of Filipino and Indonesian mixed races. The religion in Sabah is a mixture of the growing influence of Islam, but at the same time, there exist animistic beliefs such as the ‘Spirits of the Sea’ and the ‘Spirits of Rice’. The indigenous people of Sabahans of diverse backgrounds work together to carry the mats, sometimes resting and moving them around as they work. At the same time, in addition to the role of the mat in their daily lives, they also see and talk about the mat as a ‘sacred object’, as manifested in the statement ‘The mat is sacred’. From the perspective of daily life, the mats seem to be a patchwork of new folk tales, splicing their existence into the folk tales told by the indigenous people. Moreover, drifting flotsam are also transformed into physical mat constructs. At the same time, as if to illustrate the migrant community Sabah, the flotsam is also spliced in as part of the folktale.

According to Ishikura, “hybrid-gathering” involves a formative idea that renews the relationship between life and the world. This relationship is mediated by the complexity of life phenomena in which organic and inorganic matter, transcending different values and times and activated by multiple species of life, are intertwined [Ishikura 2020:51]. The criteria for the concept of “hybrid-gatherings” are (1) hybrid-gathering as a “body” that coexists with science and technology and companion species, (2) hybrid-gatherings as a “social gathering” in which individuals with heterogeneity work together, (3) hybrid-gatherings that constitutes a “symbiotic sphere” of multiple living species and inanimate objects within a given space, (4) The hybrid-gatherings as a “higher-order aggregate” of aggregates that have coexisted with different histories and mythologies, whose dimensions are integrated [Ishikura 2020:51].

Plastic waste is spliced in as material and knots’, photo by Yuto Yabumoto.

In this sense, in addition to the ‘useful object’ of the work mat, Yee exposes the hybrid-gathering formative beauty of the mat as a ‘sacred object’. (1) For the people of Sabah, it is no exaggeration to say that the mat is an expanding “body.” It takes on a hybrid-gathering co-differential corporeality as it is hybridized with plastic waste through collective movement and collaborative work. (2) The people in the images are heterogeneous and from diverse backgrounds, building ‘social gatherings’ and working collaboratively with each other. Furthermore, (3) multiple organic bodies, such as humans and fish, and inorganic substances, such as plastic waste, are intertwined, creating a ‘symbiotic sphere of the sea’ with mats as a starting point. Finally, (4) mixing different religious and national backgrounds, she creates a new communal folk tale through various narratives. In this way, Yee’s work can be evaluated as a work in which the ‘hybrid-gathering’ generation that Ishikura describes is a reality. The ‘hybrid-gathering’ embodied by Yee may be a spiral like the ‘whirlpool’ between the Sulu Sea and the Celebes Sea. As curator Sachiko Shikata (1958-) says, “The spiral also connects different dimensions by dynamically extending [Shikata 2023: 139],” while the “hybrid-gathering spiral” is an image and a moving body in which different dimensions are intertwined.

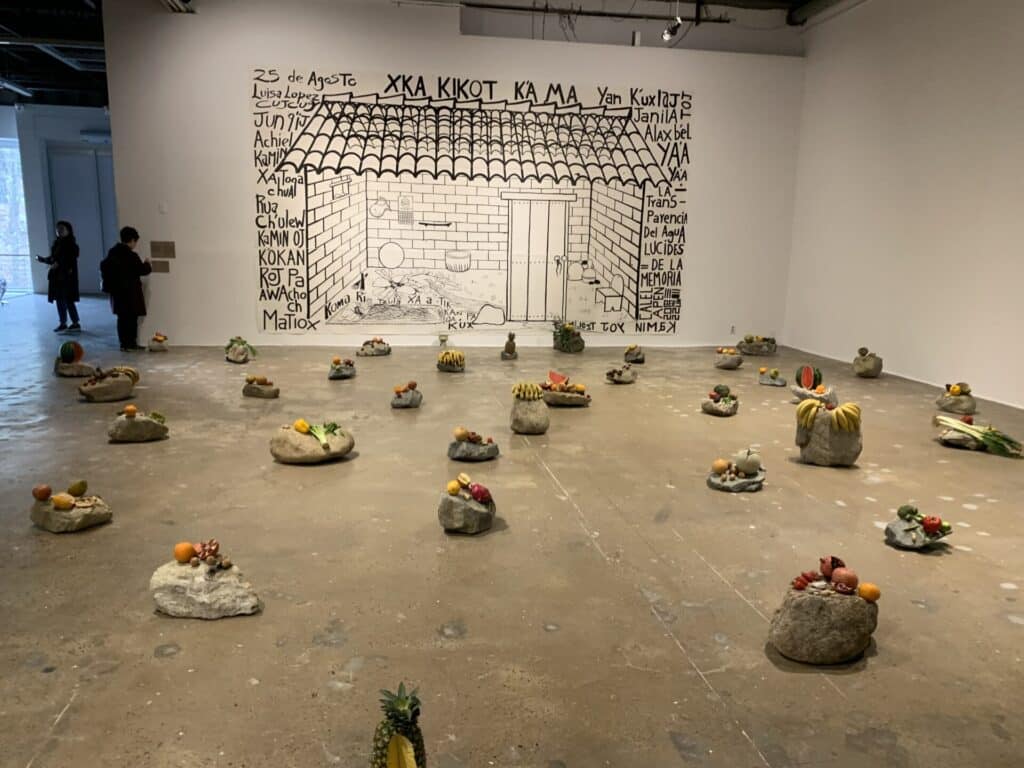

(3) Death/Grave/Tangerine.

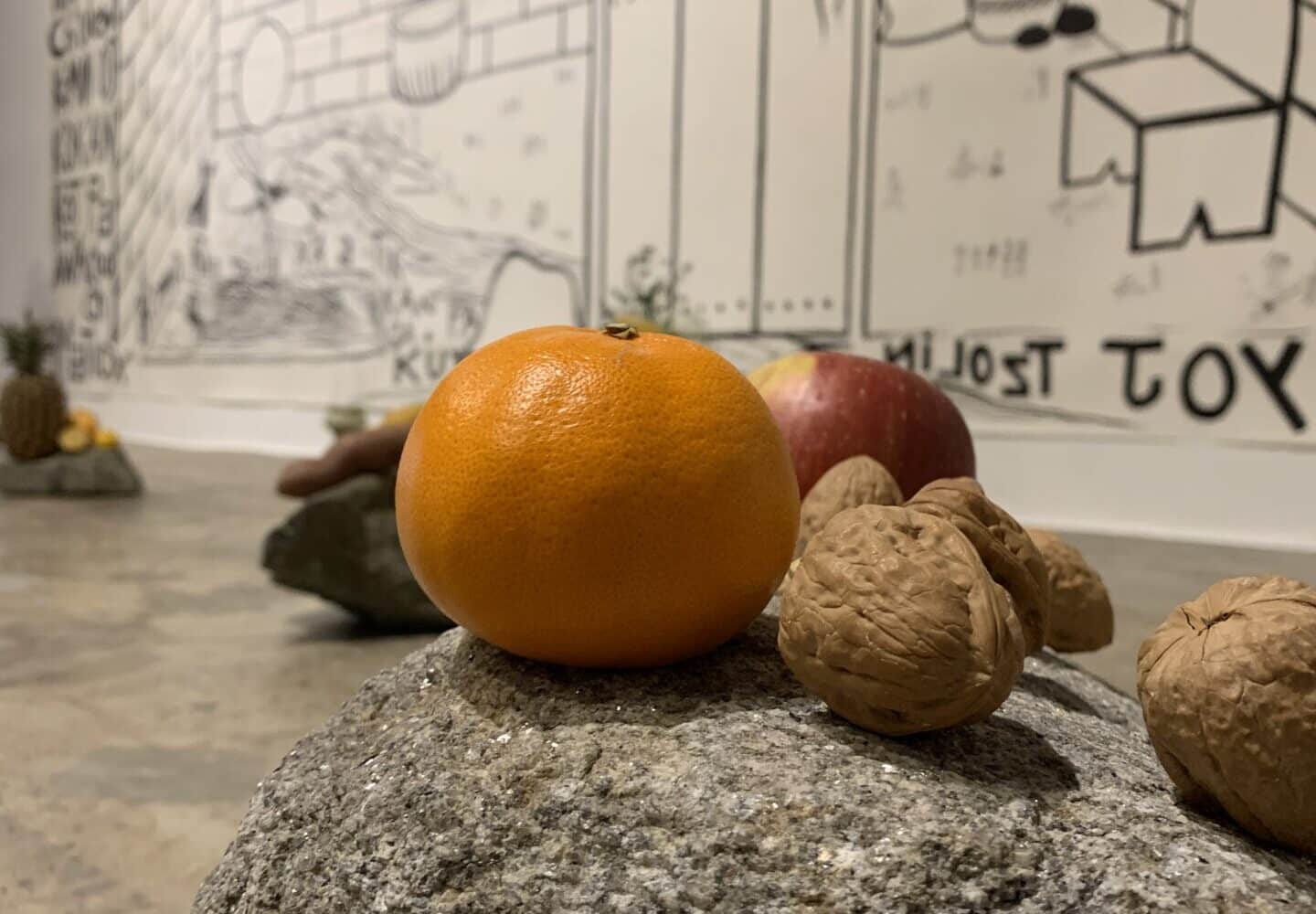

Finally, on the same floor, I finally met a ‘mandarin orange’.

It was like a sacred ‘holy object’ placed on a stone altar, like Tomoo Hirose’s Garden of Sensuality (Il giardino dei sensi, 2022), which was shown at the ‘Orange Mandala’ exhibition. As the philosopher Taisuke Karasawa (1978-) described in ‘The Brilliance of Fruit in Another Dimension‘, based on the Japanese mythological fruit, the Tachibana, the ‘oranges’ looked like a ‘spirit fruit from another dimension’ (I actually asked if I could eat the ‘oranges’ of the installation as in the ‘Orange Mandala’ exhibition, but unfortunately we were not allowed to do so). The creator of this work, Edgar Calel (1987-), is a Guatemalan artist whose ancestors are the Mayan Kaqchikel, an indigenous people living in the Guatemalan highlands. Since the arrival of the Spaniards in the 15th century, they have managed to maintain their community and survive in the face of hardships such as ethnic genocide and colonisation.

Stone altar (?). Oranges and other fruits on a stone altar’, photo by Yuto Yabumoto.

In Calel’s work, various types of fruit, such as oranges and bananas, are placed on top of stones. The caption states that they are an offering to ‘ancestors’, while the wall next to the stones is decorated with the image of Calel’s grandmother’s house and the word ‘house’ written in Kaqchikel. The French anthropologist Claude Lévi-Strauss (1908-2009) gives us a hint about the meaning of ‘house’:

A house is something different from a family in that it does not correspond to a male lineage. Sometimes, it does not even have a biological basis. Rather, it resides in material and spiritual inheritance. Such inheritances include prestige, origins, kinship, names and symbols, status, authority and wealth [Lévi-Strauss 1985: 44].

In other words, the essence of ‘home’ is not so much about ‘identity’, such as gender or blood relations, but rather about the permanent goods/locations that make up the essence of communality. Likewise, British anthropologist Janet Carsten (1941-1995) proposed the concept of ‘relatedness’ in Malaysian fishing villages, by sharing substances such as milk, and fish within the house, their body contents would be built based on those same substances. Based on this, he describes using the concept of ‘relatedness’. A ‘home’ is created not only through reproductive kinship, but also through the accumulation of acts of living together, eating together, feeding each other and exchanging things [Matsumura 2020:70]. In other words, beyond ethnicity and kinship, ‘home’ is present through living in a shared space and accumulating actions. This concept of ‘home’ is the ‘non-transferable thing’ mentioned in Mayunkiki’s discussion, and is probably the root/place of the community that connects the Kachikuker people and their ancestors.

“Exhibition hall filled with the ‘sweet smell of death’ and drawings of ‘home”’, photo by Yuto Yabumoto.

I intuited an image of a fundamental kind of ‘animism’ and ‘totemism’ from Calel’s work. In prehistoric times, people were separated from nature and lifted themselves up from it with a whimper. In doing so, people must have been shaken by the fear of ‘death’ and the fear of ‘nothingness’ that lies behind it. In order to escape from this fear of death and nothingness, primitive religion (animism) was probably born. When I was a child, my dream was to become a grape, but when I imagine it birthing from my own corpses, I feel that my fear of ‘death’ actually diminishes a little. In this way, the fundamental urge to return to nature again may have emerged as totemism (a belief in ‘totems’ (many animals and plants) that have a special relationship to a particular social group).

While the residual smell of incense and alcohol lingers from the opening ceremony, the exhibition space is filled with the sweet smell of decaying fruit. It is like the ‘sweet smell of death’. As the smell of decay suggests, the plants are dying in the exhibition space. In the process, viewers have the experience of witnessing the ‘death’ of the plants. It evokes Nancy’s ‘community of idleness’ in the first part, in which she states that ‘the community has no productive value’.

We are now doomed, or rather driven, to seek the meaning of death elsewhere than in the community. But this attempt is absurd. For it is only through death that community is disclosed, and vice versa [Nancy 2001: 26].

Nancy found human communality in the shared ‘finiteness’ of people being equally mortal.

‘Death’ is not an event experienced only by one individual, it occurs only when there is an ‘other’ to look after the death, and ‘death’ is an event that is not completed by the self alone, but is shared and accomplished jointly [Kan 2017: 146]. Here, ‘sharing’ does not mean sharing ‘sameness’, but rather the fact of being torn apart by ‘non-sameness’. In this sense, Nancy called the space created by the mutual exposure of the ‘different things that are torn apart by non-sameness and opened by being torn apart, the community of inaction’ [Osugi 1999: 218].

Photos 4-3, 4-4 ‘Rotting bananas, citrus fruits, etc., as the viewer watches the plants die’

From this perspective, Calel’s work has the potential to extend Nancy’s “community of inaction” to the non-human. ‘Death’ is not only required of humans, but of any being. In other words, the work presents the possibility of exposing interspecies communalities based on the ‘finiteness’ of plants returning to the soil, just as humans also return to the soil. It was Kumagusu Minakata (1867-1941), who has been recognised for conceiving his own philosophy of thought in Kinan, Wakayama Prefecture, while looking through a microscope at ‘slime molds’. The slime mold spreads ‘life’ through cell division. In a slime mold’s case, at the moment of division, individual slime molds face ‘death’, while at the same time multiple new individuals are ‘born’. Kumagusu must have been observing the moment of the ‘death’ of the slime fungus with an ecstatic expression on his face, while at the same time finding a ‘community of inaction’ in his relationship with the slime fungus individuals.

On the other hand, Calel’s stone work points to the foundation, the root of the living individual. For example, it points to the fact that the ‘place’ called Kongoza in front of the Linden tree in Buddhism started its roots originated from the relationship between various ‘plants’ and ‘places’, just as it was the place where humans were seated there by sitting [Ishikura, Karasawa 2021: 228, 229]. In this sense, the drawings of ‘Calel’s Plants’ and the ‘Ancestral House’ show the symmetrical connection between different species and the possibility of a pluralistic coexistence, exactly like the relationship between the ‘Linden Tree’ and the ‘Kongoza’ in Buddhism.

But why was it ‘stone’ instead of ‘soil’? This time, an interview with the artist was not possible and information on Kachikukel is limited. So, I have no choice but to interpret the work based on my imagination. On this point, the society of Sihanaka, Madagascar, gives us an insight, albeit from a different location. In Sihanaka society, since the 1970s, the ‘earth graves’ have been dismantled, and burials have been dramatically shifted to ‘stone graves’ [Moriyama 2021: 184]. As a result, ideas about ‘ancestors’ and ‘graves’ are changing dramatically.

With the increase in the number and types of ‘stone graves’, ‘graves for oneself and one’s descendants alone’ were created in the form of branches and offshoots of the graves of the Shihanaka people. As a result of the increasing individualisation of graves, rituals and taboos were abandoned, causing discord and friction among relatives [Moriyama 2021: 204-207]. Furthermore, the personalisation of graves has increased the financial burden, and the gap between the ‘haves and have-nots’ has become more visible [Moriyama 2021: 213-126].

(*For background information and other details, see Moriyama Ko, ‘Gifts and Sacred Objects: Marcel Mauss’s “Gift Theory” and Social Practice in Madagascar‘).

This is related to the question of how to view ‘ancestors’. One is the way of thinking of each ancestor as an individual being. The other is the way of thinking that considers ancestors not as individuals, but as a single, whole existence. In other words, the former is a named ‘ancestor’ with an individual personality and names, whereas the latter sees ‘ancestors in general’ as ‘ancestors’, taken in an undifferentiated state. I do not know whether Kachikkel is in the same state of mind about these ‘earth tombs’ and ‘stone graves’, but looking at Calel’s work again, I felt that he was seeking a rethinking the way of being towards ‘ancestors in general’ and a return to ‘earth graves’.

Choose an appropriate date in the dry season to open the ‘earth tomb.’ All the corpses in the tombs are then moved to new ‘stone tombs’. After the reburial, the ‘earthen grave’ is then emptied. Therefore, a banana tree is planted at the bottom of the hole in the ‘earthen grave’ as a replacement for the corpses [Moriyama 2021: 181].

As stated above, the reason why the people of the Sihanaka community plant banana trees in earthly graves is probably because they cannot fully abandon their ‘ancestors in general’ who return to the earth even after it is emptied. In other words, they might have a hope that their ancestors will live on, becoming banana trees. In light of this perspective, Calel confronted ‘modern people’s tendency to change their attitude towards the decay of the dead.’ By replacing the plants on the stones again, perhaps, Calel is trying to re-propose views on ‘ancestors’ based on animism and totemism.

‘Tangerines (ancestors?). ‘Together with the guests, we entertain our guests’.

Finally, there was a sense of déjà vu in the imagery of Calel’s exhibition.

Indeed, it is the same composition as the ‘feast’ of the Orange Mandala exhibition.

Let me compare the two. Calel’s grandmother’s house could be like the orange warehouse which was the main venue of the exhibition, the “place” of stones/chairs where we sit, and various “plants,” including mandarin oranges/oranges, the people of Kinan and the visitors to the Gwangju Biennale, “people living in the present,” and the invisible “ancestral spirits,” are all intricately mixed together. Both Calel’s and what we are trying to create represent an open “feasting place” for every being.

We made ‘mandarin oranges’ and ‘citrus juice’ the object of sacrifice and entertained guests (others), known or unknown. On the other hand, Calel’s work attempted to engage with both our ancestors and the viewers who live in the present through rituals at the Gwangju Biennale, together. This is connected to the origins of animistic festivals that share roots with the Japanese Obon Festival and Mexico’s Day of the Dead. As Calel shows, the undifferentiated and inclusive ‘ancestors in general’ and communal work is still important in the indigenous world. This ‘place of feasting’ is what Morse describes as ‘the “fundamental act” of gaining “approval” from the “other” in general’ [Moriyama 2021:283], and is an act of hybrid gathering that transcends time and space, animistically giving ‘something of itself’ to the other while retaining the self, and giving the other to the other, as in Mayunkiki’s message. It is the very act of the coeternal.

However, I believe that indigenous art is born out of the derivation of a certain communal fantasy, and if the element of ‘ancestry’ becomes too large, depending on the situation, there will be a possibility that it may be reduced to an ‘ethnic community’. This problem of an ‘ethnic community’ is also the barrier that the German philosopher Martin Heidegger (1889-1976) faced in examining the relationship between ‘nation’ and ‘community’. Considering this, it is important to find a state in which pluralistic elements coexist in different species/multispecies and at different times, transcending ethnicity, on the basis of the four criteria proposed by Ishikura. In this sense, it is regrettable that in Calel’s work, I was unable to obtain the symbolic physical meaning of ‘eating an orange.’

On the other hand, while Blanchot’s ‘unidentifiable community’ and Nancy’s ‘community of inaction’ are certainly effective as ideas to avoid totalitarianism, there are doubts about the validity of a community based on ‘aimlessness’ and ‘unproduction’ in contemporary society, which is riddled with goals and objectives. In the second part of this article, I would like to further consider the nature of contemporary community/communion, focusing on the works of Japanese artist Meiro Koizumi (1976-) and South African artist Buhlebezwe Siwani (1987-), in relation to the ‘in between’ of these arguments.

<References>

- Ishikura Toshiaki, “‘Cosmic Eggs’ and the Generation of Coheresy: from the Japanese Pavilion Exhibition at the 58th International Art Exhibition of the Venice Biennale”, Tatui Vol. 2 Special 1: The Horizon of Coheresy, Aki Shobo, 2020.

- Ishikura, Toshiaki and Taisuke Karasawa, ‘Anthropology of the external organs and coeval bodies’, More Than Human: Multispecies Anthropology and Environmental Humanities, Ibunsha, 2021.

- Tomiyuki Uesugi, Social and Cultural Responses to ‘Crossing Borders’ in Sabah, Malaysia: ethnic reorganisation in the dynamics of cultural associations, Seijo University Bulletin, 2002.

- Takashi Osugi, The Creole of Inaction, Iwanami Shoten, 1999.

- Taisuke Karasawa, ‘The brilliance of fruit in another dimension’, Kinan Art Week website (https://kinan-art.jp/info/10784/, viewed on May 2023).

- Sachiko Shikata, Ecosophic Art – Art Theory Connecting Nature, Spirit and Society, Film Art, 2023.

- Giorgio Agamben, Tadao Uemura (trans.), The Coming Community, Gekkisha, 2012.

- Koko Suga, The Form of Community: On Images and People’s Existence, Kodansha, 2017.

- Nagatsu Kazufumi, Living the Border: A Dynamic Ethnography of Sabah, Malaysia, Kaisama, Kisai-sha, 2019.

- Keiichiro Matsumura, Hamidashi no Anthropology: How to live together, NHK Publishing, 2020.

- Marcel Mauss, Moriyama Takumi (trans.), The Theory of Gifts and Two Other Essays, Iwanami Bunko, 2014.

- Takumi Moriyama, Gifts and Sacred Objects: Marcel Mauss ‘Gift Theory’ and Social Practices in Madagascar, University of Tokyo Press, 2021.

- Takumi Moriyama, The Idea of ‘Gift Theory’ – Marcel Mauss and the Logic of <Mixing>, Inscript, 2022.

- Maurice Blanchot, Osamu Nishitani (trans.), The Unveiled Community, Chikuma Shobo, 1997.

- Mai Hachiya, ‘Ainu Life from the Sinuye Perspective 3’, Sinuye Study Group, 2023.

- Levi Strauss, ‘Historiography and Anthropology’, Thought No. 727, Iwanami Shoten, 1985.

- Roberto Esposito, Onji Okada (trans.), Deconstruction of Modern Politics: Community, Immunity and Biopolitics, Kodansha, 2009.